Election integrity, voter turnout among top priorities for secretary of state candidates

In the November race for California secretary of state, the candidates — Republican business executive Robert Bernosky and incumbent Shirley Weber, a Democratic former lawmaker — seem to agree on one thing: the need to boost voter registration and turnout at the polls.

The secretary of state serves as California’s chief elections officer and provides voters with information about ballot measures, statewide candidates, campaign financing and lobbying activity in Sacramento. The agency also oversees business licensing and filings in the state.

California is already among the easiest states to register and vote, with 81% of eligible residents signed up, thanks to recent laws that expanded voting rights and access.

Yet during their campaigns, both Bernosky and Weber said they have seen growing apathy among voters. They say some Californians feel as though their vote doesn’t matter, or that they lack an adequate understanding of current political issues. Others say they are simply too busy to show up at the polls or to drop off or mail in their ballots.

Bernosky hopes to motivate voters to elect leaders who advocate for pro-business policies, lower taxes and other conservative initiatives to create more “balance” in the state Legislature, which he said is “putting California out of business.”

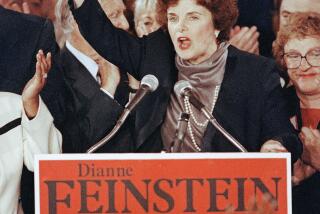

Competing for the California secretary of state election are Shirley Weber, 74, the Democratic incumbent, and Robert Bernosky, 59, a Republican businessman.

Leaning on his experience with investors as a businessman, he said he regularly works with voters, selling them on the idea to “invest in California” by voting.

“We need to make the California Republican Party relevant again in California to provide that balance, and that’s what I hope to do,” said Bernosky, who represented the Central Coast as regional vice chairperson to the state Republican Party between 2016 and 2020.

Bernosky may have a difficult time getting the word out to voters, however. He’s raised almost no money for his campaign, according to state campaign finance records.

Weber has raised about $1.4 million.

Weber said her approach to the job has been less partisan since Gov. Gavin Newsom appointed her to the office in 2021 to fill a vacancy created when Alex Padilla left the post for the U.S. Senate. Weber, a college professor before entering politics, became the first Black woman to serve as California’s secretary of state.

Weber, who spent four terms as a member of the state Assembly representing portions of San Diego County, authoring influential bills on education and racial justice, said she is proud of her ability to build bridges and win bipartisan support.

She made it a priority during her short term as secretary of state to promote awareness of the voting rights accomplishments of her predecessors — preregistration for 16-year-olds, same-day voter registration, and the right for felons on parole to vote— and to support laws such as making permanent the pandemic-inspired policy to send mail-in ballots to every Californian who is registered.

“We’ve been trying to help them understand the power of who they are,” Weber said, referring to speaking tours at college campuses and high schools across the state in an effort to register more young voters, whose turnout typically lags. “Because maybe they felt so disempowered, and to help them understand that your vote is one vote, and it’s as powerful as mine and it’s powerful as the governor’s.”

In the June primary, Californians provided a vote of confidence for Weber’s first term. She won nearly 60% of the vote, compared with Bernosky’s 18.6%.

Although Bernosky praised recent expansions in voter access, he cautioned against possible security pitfalls. He pointed to problems with the 2018 rollout of the state Department of Motor Vehicles’ “Motor Voter” program, which automatically registered eligible residents to vote when signing up for a driver’s license or state identification. The program incorrectly registered thousands of voters with faulty information, including some who were not eligible to vote, such as noncitizens.

Following two unsuccessful bids for state Assembly and after serving on the Hollister School District Board of Trustees in his native San Benito County, Bernosky said the DMV program’s issues prompted him to consider running for secretary of state.

A supporter of former President Trump, Bernosky acknowledged the threat of election deniers after the pro-Trump mob attacked the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, to prevent Congress from formalizing President Biden’s victory, but said they do not represent the majority of conservative voters in California.

To erase any lingering skepticism in the electoral process, he said he plans to tighten voter rolls, making sure there are no duplicate names, and to enhance the signature verification process.

“I just want to remove any doubt about the quality of our elections,” Bernosky said.

Weber assured that her predecessors already audited and fixed issues with the DMV program, which registered more than 1 million voters in its first year. She said there is room to improve the system of counting votes, which she admitted has its glitches, but pointed to the June primaries as proof of a smooth election system.

If elected, Weber also plans to restart conversations with lawmakers about reforming the state’s recall process, which, after overseeing last year’s Republican-led failed recall effort against Newsom, she said is due for change. Among proposed changes would be to install the lieutenant governor in office if a governor is recalled instead of selecting a replacement in the same vote. In a recall election, the candidate who receives the most votes wins — no matter how many votes he or she receives.

“With whoever becomes governor, we should actually have some sense of confidence that they are really going to represent us, and not just a fluke that somebody got in and didn’t have as many votes as the governor who got thrown out,” Weber said.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.