Column: In Ukraine, anti-Trump strategists take on Russia and Putin

Over the last two decades, Mike Madrid has battled Democrats, Republicans, Donald Trump and a pesky family of squirrels that assumed residence in the eave of his Midtown Sacramento home.

His latest mission is taking on Vladimir Putin and the substructure of lies and misinformation the Russian leader built to support the invasion and attempted takeover of Ukraine.

“This is a war of the digital age, of the information age,” Madrid said via encrypted cellphone, before a meeting in the western Ukrainian city of Lviv with the Zelensky administration. “And the Ukrainians are incredibly sophisticated in the way they’re developing messaging and building infrastructure to fight back.”

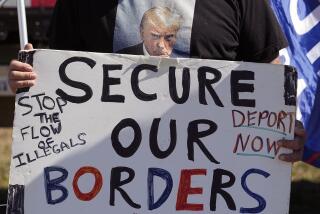

Madrid, a Republican campaign consultant, has spent much of his political career tackling tough causes, including fighting within his party to broaden the GOP’s appeal to working-class and Latino voters, end the scapegoating of immigrants and stand up to the bigotry and boorishness of Trump.

(His battle with squirrel invaders, featuring the flummoxed Madrid as a real-life Elmer Fudd, racked up hundreds of thousands of views on Twitter and turned his feed into an international clearinghouse for all things squirrel.)

Russian bombs wrecked a small museum holding works by one of Ukraine’s best-known artists, Maria Prymachenko. But townspeople rescued a national legacy.

The goal during a stealthy 10-day visit to Ukraine, Madrid said, was to help the country strengthen its social media presence by applying some of the lessons he and others learned in the 2020 campaign as part of the Trump-tormenting Lincoln Project.

One was the “need to use humor and humiliation against a tyrant to lessen people’s fear,” Madrid said. “It’s better to make [Putin] a clown than a devil.”

His focus at the Lincoln Project was reaching out to persuadable voters in key portions of battleground states. TV advertising and viral videos were the most attention-grabbing (and lucrative) aspect of the group’s strategy. Madrid’s efforts were surgical strikes aimed at undermining Trump and helping Joe Biden by harnessing information to analytics.

He placed digital advertisements, one after another, and then gauged their effect in real time, using a series of metrics — shares, likes, time spent watching — to determine which messages performed best. It was a master class in online engagement.

Soon after the election, Madrid left the Lincoln Project. The departure followed an acrimonious split with some of its founders, who faced allegations involving sexual harassment and financial self-dealing.

Despite that unhappy ending, Madrid’s connection to the insurgent effort led in roundabout fashion to Ukraine. A filmmaker and specialist in information warfare, who is producing a Lincoln Project documentary, introduced Madrid and Ron Steslow, a fellow Lincoln Project alum and host of the Politicology podcast, to Ukrainians fighting Russia online.

Earlier this month the two traveled to Ukraine, accompanied by a Russian information specialist — unnamed here for safety reasons — to help wage war against Putin on Facebook, Twitter and other social media.

The three met furtively with academics and political activists. They huddled with cyberwarriors and senior members of Zelensky’s administration. They shared ideas on targeting audiences to counteract Putin’s propaganda, ways to penetrate Russia’s closed society to tell the true story of the invasion, and methods of engaging millions of pro-democracy allies around the world.

They came away impressed with the expertise of the resistance and the fortitude and determination of those in its ranks.

“The Ukrainians know their history,” Madrid said. “They will all die before letting Russia take their land. They know what the Russians will do to them. Look at Bucha and Irpin,” cities where Ukrainians say hundreds of civilians were massacred. “They know.”

Three Ukrainians have found refuge, and a way to share the recipes of their homeland, in a fancy Paris restaurant.

Madrid spoke from a hillside outside Lviv, overlooking a series of small plots where farmers were putting down seed. It was a quiet break from air-raid sirens, roadside checkpoints and hushed meetings in darkened apartments. A patchy phone connection faded in and out.

For more than a decade, he noted, Russia has been waging cyberwar on Ukraine, the United States and other countries. After interfering in the 2016 presidential campaign, to the benefit of Trump, Putin and his troll farms continue to flood social media with content aimed at dividing Americans over politics, race, pandemic restrictions and other issues.

Fighting back will require new alliances across political parties and national borders, said Madrid, who started flying home Wednesday.

“We all agreed,” he said of his newfound compatriots, “this will be the future of cyberwarfare. ... Networking to bring down regimes that threaten the rise of authoritarianism. Ukraine has built the infrastructure for what that looks like.”

Now, he said, it’s up to others around the world to expand and build on those pro-democracy efforts.

More to Read

Get the latest from Mark Z. Barabak

Focusing on politics out West, from the Golden Gate to the U.S. Capitol.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.