Column: The cost of China’s harsh ‘zero COVID’ policy? Human suffering and economic damage

WASHINGTON — The stories from Shanghai, a city of 25 million entering its fourth week of COVID-19 lockdown, have been harrowing.

Millions have been confined to their homes, their movements monitored by pandemic police in white hazmat suits. Almost 300,000 people who’ve tested positive or had contact with someone positive have been forcibly moved to spartan quarantine centers.

Videos on social media have shown people fighting over food or screaming for help from their apartment windows: “Save us! We don’t have enough to eat!”

Police took children who tested positive and sequestered them, away from their parents, in state-run hospitals — a policy reversed only after an outcry from distraught mothers.

For over two years, China’s response to the pandemic has been the draconian approach known as “zero COVID.” It succeeded in stopping the virus’ spread in 2020, when no vaccines existed and exposure was more often fatal.

Now, though, most infections stem from the relatively mild Omicron variant, and an enviable 88% of people in China are fully vaccinated. Shanghai has reported more than 220,000 COVID cases since March 1 but has officially acknowledged no deaths from the surge.

Still, the government’s response has been total lockdown.

President Biden can rightly tout several successes: record job growth, landmark legislation, a NATO alliance unified against Russia. But voters remain anxious about the economy and the world, and he’s paying the political price.

The result has been the needless disruption of millions of lives and a blow to the world’s second-largest economy, with effects that will ripple across the world.

The damage is impossible to estimate with any accuracy, but big enough that Premier Li Keqiang warned publicly last week that the economy faces “unexpected challenges and mounting downward pressures.”

In Greater Shanghai, China’s economic capital, workers cannot reach their jobs. Construction projects have halted. Assembly lines for Tesla, Volkswagen, Apple and other major brands have suspended operations.

Supply chains are in chaos. Truck and train traffic have plunged. And according to unofficial reports, hundreds of container ships are stuck unloaded in the region’s ports.

The problems aren’t confined to Shanghai. Japan’s Nomura Bank reported last week that 45 Chinese cities, with almost 400 million inhabitants total, were in some form of lockdown.

The government in Beijing hasn’t changed its official target of 5.5% growth for 2022, but economists say that number looks unattainable now.

Until recently, many Americans thought of China as a juggernaut that would soon overtake the United States to become the largest economy in the world — a meaningless landmark, but one that comes with bragging rights.

Two years ago, the Japan Center for Economic Research predicted that the crossover point would come in 2029. Last month the think tank revised its projection to 2033, four years later.

In the face of all that adverse data, you might expect China’s leaders to soften the zero COVID policy for the sake of economic growth. That’s what has happened, at least tacitly, in the United States, where the Biden administration has relaxed its COVID recommendations in view of the diminished threat of fatalities.

Not in China.

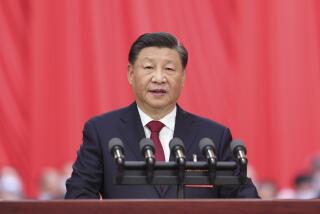

“Prevention and control work cannot be relaxed,” President Xi Jinping said last week. “Persistence is victory.”

The problem is political: Zero COVID has been one of Xi’s signature policies, and he doesn’t appear interested in diluting it — especially as he approaches a Communist Party Congress this fall that is expected to award him a third five-year term.

“We often think of China’s political system as adaptive and decentralized, but under Xi’s strongman politics it’s neither of those things,” Susan Shirk, a China expert at UC San Diego, told me. “Xi sometimes make mistakes, but nobody dares to tell him. Instead, there’s a bandwagon effect; party subordinates often overshoot, because they want to stand out as the most loyal.”

In a democratic country, a leader would worry about bad economic news in the middle of a reelection campaign.

Xi doesn’t have that problem; there’s no sign of a challenge to him from the party ranks.

Besides, this year’s economic slowdown, which began even before the lockdown in Shanghai, is probably only a short-term problem.

But Xi still faces a long-term economic challenge. His larger goal is to move China into the ranks of advanced high-income countries.

Since Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms in the 1970s, China has grown prosperous thanks largely to low-wage export manufacturing and a seemingly inexhaustible supply of workers.

But one of Xi’s core promises is that a modernizing economy will deliver higher wages. Meanwhile, China’s population — and its workforce — are projected to shrink, a product of its old “one-child” policy.

The United States has long exerted influence over Central America. Now, China wants in — and the region’s countries are welcoming.

“They need to develop a new growth model,” Aaron L. Friedberg, a China scholar at Princeton University, told me. “Xi’s answer has been to try to leap ahead in technology and increase workers’ productivity as they lose their low-wage advantage.”

But he faces a potential political contradiction.

“They’re betting that they can be just as innovative as we are while keeping the flow of information under control inside the country,” said Friedberg, author of “Getting China Wrong,” a new book on U.S.-China policy. “It’s not clear that it’s going to work.”

Meanwhile, he said, Xi is employing another time-honored device to bolster domestic support for his regime, even in the face of an economic downturn: unbridled nationalism.

“The regime has deliberately ratcheted up the sense of antagonism between China and the West,” Friedberg said. “And it’s actually been quite successful at that.”

When China accuses the United States of being at fault for Russia’s decision to invade Ukraine, he said, Americans and the Biden administration aren’t its main audience.

“I don’t think it’s aimed at us,” he said. “It’s aimed at the domestic audience and at the developing world — showing that China is emerging as the leader of the global south, willing to stand up to the West.”

Russia’s war in Ukraine will end someday. When that happens, China — with its economic challenges and its ambitions of international leadership — will reassume its status as the most important global rival to the United States.

Get our L.A. Times Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.