Analysis: Biden’s State of the Union speech takes aim at Putin, and poll numbers

In his State of the Union speech a year after taking office as the un-Trump, President Biden faces an American public that wants far more.

WASHINGTON — Early in his State of the Union address Tuesday night, as President Biden reeled off the devastating economic sanctions against Russian President Vladimir Putin, he sounded a bit like he was trying to channel Dirty Harry.

“He has no idea what’s coming,” Biden said in a threat to Putin that sounded personal and appeared ad-libbed.

This was Biden as a quasi-wartime president, absent the actual American troops: talking tough about the fight for freedom in Ukraine against a foreign enemy, and capitalizing on American unity to sell his domestic agenda.

“We will meet the test,” Biden said at the climax of his speech. “To protect freedom and liberty, to expand fairness and opportunity. We will save democracy.”

Biden has reached the kind of “inflection point” he often invokes — confronting the unpredictable war in Europe, a crisis in democracy at home, a pandemic that has lingered, a stalled agenda in Congress and an American public anxious over inflation.

Underneath these challenges lie questions from the public over whether Biden is a strong enough leader to confront the maelstrom. In

a Washington Post-ABC News poll taken last week, 59% of Americans said no, compared with 49% who gave that answer just before he secured the Democratic nomination in 2020.

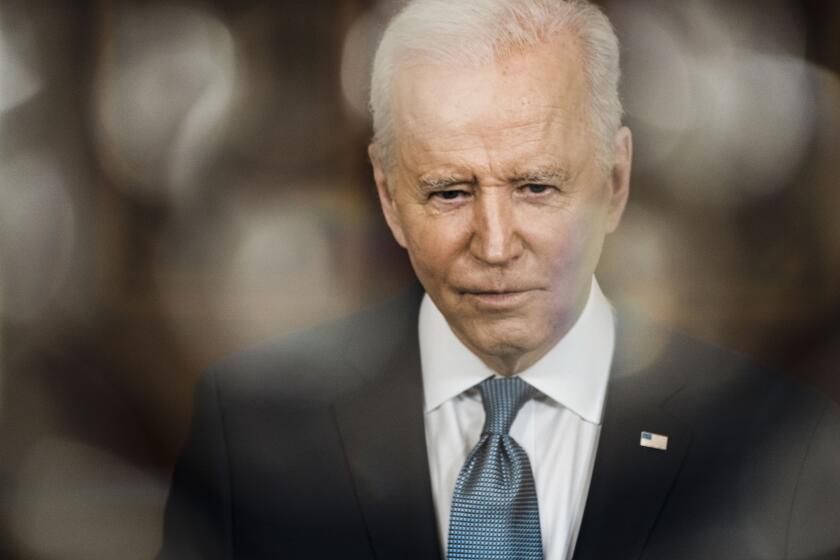

President Biden delivers his first State of the Union speech amid geopolitical and domestic crises that challenge his presidency.

Concerns over the strength of Biden’s leadership, reflected in a variety of polls, follow sustained attacks from the right claiming he is mentally unfit. But these worries also have spread to voters in his own party and especially to independents, who worry he is losing steam, even if they don’t buy Fox News’ portrayal of him as doddering.

Favorable perceptions of Biden declined noticeably after the chaotic withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan undermined his administration’s case that it had restored competency to government.

“Without using the phrase ‘return to normalcy,’ he was viewed that way by a lot of people,” said Mary Kate Cary, a speechwriter for President George H.W. Bush. “The rest of the world didn’t get the memo.”

Much of the desire for normalcy was based on fatigue with President Trump and the sense that Biden would bring empathy, an end to division, and stability. Celinda Lake, one of Biden’s campaign pollsters, argues the president has passed the first two tests, but concedes the third objective — stability — has been elusive.

A suburban woman in one of Lake’s recent focus groups summarized the feeling: “I just want off this roller coaster.”

Lake believes the war in Ukraine, however bleak, offers a window for Biden to demonstrate that his quiet form of leadership has worked — relying on experts; lobbying European allies behind the scenes to impose painful sanctions against Russia; and communicating candidly with the American people.

The full text of President Biden’s prepared remarks for his first State of the Union address, delivered amid a pandemic, inflation and war.

In his State of the Union address, Biden made a point of calling out Putin for a “premeditated and unprovoked” invasion, while warning that when “dictators do not pay a price for their

aggression, they cause more chaos.” He announced new action to match the tougher talk, banning Russian planes from U.S. airspace.

“American diplomacy matters,” Biden proclaimed Tuesday, drawing an implicit contrast with Trump, who disdained NATO and other multinational organizations.

The president argued that Putin had underestimated the unity of America and its allies.

“Putin was wrong,” Biden said. “We were ready.”

But even as Biden lauded Western resolve against Putin, his tone could backfire, given the suffering that has already begun in Ukraine and the potential for a broader conflict with a nuclear power.

Biden vowed to use American troops only if it becomes necessary to protect NATO countries. So his promise to “save democracy” could sound hollow to some ears in Ukraine, which is not part of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

The speech comes among a stalled legislative agenda, rising inflation, declining public support and an escalating war in Ukraine

He conceded the need to “remain cleareyed,” cautioning that although “Ukrainians are fighting back with pure courage ... the next few days, weeks, months will be hard on them.”

The relative unity in the U.S. and among allies over the war, however, presented Biden the opportunity to frame his domestic challenges as part of a global struggle between democracy and the growing forces trying to upend it, including Trump’s baseless claims to being the rightful president.

It also allowed Biden to recast his domestic vision in more bipartisan terms, after a year in which he struggled to get his more progressive plans through narrow Democratic majorities in Congress.

He framed his climate agenda as a way to cut soaring energy costs, his immigration bill as a step toward securing the border, his tax hikes on corporations and the wealthy as a way to fix a broken system. He emphasized the importance of funding police departments, even as he urged an overhaul of discriminatory practices.

Biden conceded Republicans would disagree with some of those assessments, but practically begged the opposition party to sign on to his “unity agenda,” which included plans to fight the opioid epidemic, help veterans, defeat cancer and increase access to mental healthcare.

“I don’t see a partisan edge to any one of those four things,” he said in an aside.

Biden’s 41% approval in polls is at its lowest ebb to date, only fractionally better than Trump’s standing at this point in his presidency and considerably worse than that of most of his predecessors. It’s hard to turn the tide with a speech, but the State of the Union offered Biden a rare chance to reach viewers who do not linger on Twitter or spend their days watching cable news.

Presidents and their speechwriters usually start writing the address months in advance, hoping to tell a story and convey a simple vision rather than a laundry list of proposals.

Cody Keenan, President Obama’s former lead speechwriter, remembers sitting with Obama and laying out plans to break the laundry list mold. But the competition among policy aides to get even a line in the speech — which can propel an issue to relevancy inside the federal bureaucracy — is too fierce to resist. Keenan said advisors staked him out in the bathroom to make their pitches.

Biden’s advisors began sending out a string of policy fact sheets and giving background briefings Monday, creating a list of priorities so long that few Americans will be able to remember many of them.

Those who worry about the president’s vitality may instead recall his uneven delivery. Biden flubbed a number of his lines in his hourlong speech, at one point speaking about the “hearts and souls of the Iranian people” when he intended to speak about the resolve of the Ukrainian people.

His pace picked up toward the crescendo, however, as Biden pointed, clenched his fist and told the country to “go get ’im.”

Biden hopes the speech will give new life to his agenda and perhaps begin a resurgence for a Democratic Party that is expecting big losses in November’s midterm elections. And like his predecessors, he is likely to get at least a small bump in the polls. But changing longer-term perceptions about his presidency is a harder lift.

“The State of the Union is probably one of his better chances to do that, but let’s not over-torque it,” Keenan said. “It’s one of the most important speeches, but let’s be honest: Most Americans forget it after two days.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.