SAN JUAN, Puerto Rico — Kemuel Delgado rolls his eyes as he drives down a highway and sees a sculpture featuring Christopher Columbus, called “Birth of the New World,” looming over the Atlantic coastline. It stands taller than the Statue of Liberty.

This tribute to the explorer who landed in Puerto Rico in 1493 is just another reminder of how Delgado’s people endured 400 years of Spanish rule before the U.S. took control in 1898, treating islanders as colonial subjects in its own way.

“As someone who has lived colonialism,” says Delgado, 23, “I’ve never known freedom.”

Though granted U.S. citizenship in 1917, Puerto Ricans who reside in the island territory aren’t allowed to cast ballots for president, and they’re denied voting representatives in the U.S. House and Senate.

Delgado says it’s hard to live with the humiliation of having “one foot in and one foot out” of your own country. In that sense, he feels a kinship with the millions of activists and other citizens across the U.S. who since George Floyd’s murder in 2020 have sparked a national conversation about the different ways Americans of color are made to feel that they’re undeserving of respect.

As a Black man in America, I’ve always struggled to embrace a country that promotes the ideals of justice and equality but never fully owns up to its dark history of bigotry, inequality and injustice.

Now, more than any time in recent history, the nation seems divided over this enduring contradiction as we confront the distance between aspiration and reality. Join me as I explore the things that bind us, make sense of the things that tear us apart and search for signs of healing. This is part of an ongoing series we’re calling “My Country.”

He and many others in his territory hope that even with a host of other priorities competing for attention in Washington, sympathetic Democrats who now control the White House and Congress will finally show them that they truly belong by allowing Puerto Rico to become a state.

“In a democracy that preaches justice and freedom for all,” Delgado says, “why should I have to ask for something that is my birthright?”

And yet, even as Delgado yearns for statehood, he’s begun to reexamine his own identity as a Puerto Rican and to reflect on the ways that racism and inequality in the territory mirror the divisions he sees on the mainland.

“We’re here to stay”: Black Californians put down roots in the desert

The island’s former glory as a vital transit point for captive Africans flowing into the Americas — and for gold and silver flowing back to Europe — is evident from the moment the cannon towers and hulking ramparts of Old San Juan come into view on the descent into the city’s airport.

Imposing walls encircling the old town took 200 years to build, mostly using the forced labor of slaves. By a clifftop lighthouse, children now fly kites in the trade winds that once ushered in ships loaded with human cargo.

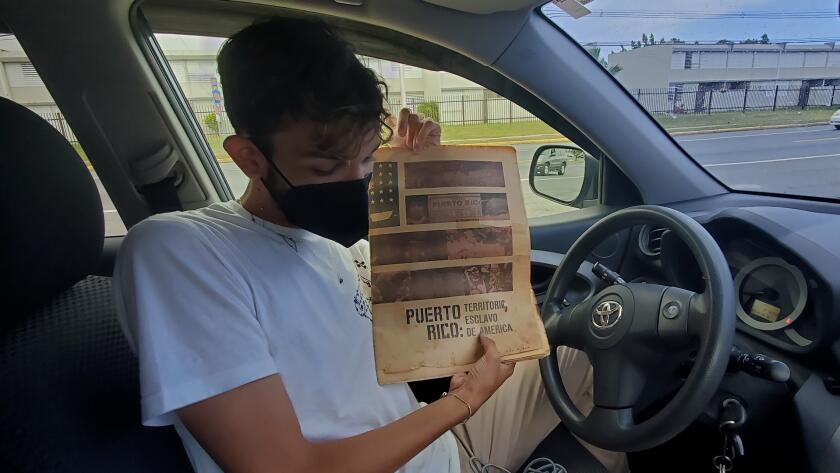

While shopping recently in a store in Old San Juan, Delgado came across a yellowing newspaper with frayed edges that helped him connect Puerto Rico’s struggles to the broader movement for racial justice.

“Everything changed for me when he threw paper towels at us. It’s like there’s before Maria and an after-Maria.”

— Kemuel Delgado, on then-President Trump’s behavior in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria

It’s a copy of a pro-independence publication from the 1960s, filled with articles lashing out at attempts by lawmakers at home and in Washington to prevent Puerto Ricans from flying the island’s flag or determining their own future.

Delgado unfolds the paper to reveal the front-page headline that had caught his attention, printed in big, bold type: “PUERTO RICO: TERRITORIO ESCLAVO DE AMERICA.”

Puerto Rico: America’s slave territory.

Delgado is slender, soft-spoken and exceedingly polite. As he takes me around San Juan and surrounding towns, he expresses gratitude for the chance to show his fellow citizens a view of America from the vantage point of the people who live here.

Puerto Rican statehood advocate Kemuel Delgado wants his fellow Americans to see his fight as part of the national conversation on inequality.

He’ll never forget President Trump’s visit to the island after Hurricane Maria in 2017, when he casually tossed rolls of paper towels into a crowd of residents and joked about withholding federal aid, all while they were suffering from widespread destruction, power outages and a lack of food and water.

“Everything changed for me when he threw paper towels at us,” Delgado says. “It’s like there’s before Maria and an after-Maria.”

He’s been an advocate for making Puerto Rico a state ever since, helping to organize demonstrations and establish a nonpartisan pro-statehood coalition on the island, traveling to the mainland to meet with Democratic and Republican lawmakers, and tweeting about the power of the Latino vote to the 6 million Boricuas, as Puerto Ricans call themselves, who happen to live stateside. He’s even temporarily relocated to Connecticut, the state with the highest concentration of Puerto Ricans, to continue his efforts in the region.

While giving a tour of the island earlier this year, Delgado drives west of San Juan’s beach resorts into the countryside. Dome-like hills called mogotes spring from pastures that glow emerald green in the sun. Leafy vines resembling Mississippi kudzu drape limestone outcroppings. Flowering trees splash the roadsides with bright coral.

”This is the real Puerto Rico,” says Delgado, who was born in the beachside town of Hatillo, where support for statehood is strong and residents joke that there are more cows than people.

Nearby, in the old pirate hideout of Quebradillas, statehood supporter Edgardo Díaz sits among buildings in various stages of disrepair and recalls going without electricity for five months after Maria.

Puerto Ricans pay taxes that fund federal social programs including Medicaid and food stamps, but receive less federal aid than citizens living in the States, which only exacerbates problems caused by rampant corruption and a poverty rate that exceeds 40%.

“It tires you,” the 22-year-old Díaz says of Puerto Rico’s inability to provide basic services.

Though 52.5% of voters in Puerto Rico said yes to statehood in a nonbinding referendum last fall aimed at showing the idea had broad appeal, the island faces daunting obstacles in Washington.

The U.S. Constitution requires Congress to consent to any territory becoming a state, and that’s traditionally granted by a simple majority vote in both houses. But with the sharply divided Senate, and firm opposition from key Republicans and even some Democrats, supporters’ chances of victory look slim.

Despite renewed attention on Puerto Rico’s status this year — the introduction of bills in the House and Senate regarding its future and a House committee hearing in March — Delgado believes something’s missing from the statehood conversation.

About 1,500 miles north, in the nation’s capital, anti-racism activists who support making the District of Columbia a state argue that D.C. residents have been deprived of full representation because the population has historically been majority Black.

But among Puerto Ricans, Delgado says, there’s a reluctance to see prejudice against Black and Latino Americans as a factor in their struggle. It fits what he sees as a larger pattern of avoidance when it comes to the subject of race.

The island’s population today is a mix of European, Afro-Caribbean and Taíno, the Indigenous group that was nearly wiped out by the Spanish conquest.

Blackness elicits special hostility. Not only do Puerto Rican entertainers, TV personalities and politicians often play on negative racial stereotypes, Delgado says, many people use derogatory expressions when referring to Black people in conversation.

“Not having much that was passed down from generation to generation, I found myself trying to understand my grandfather and what it meant to be a Black man in Puerto Rico.”

— Kemuel Delgado, who grew up with tan skin around people with European features

Yet in a society that’s proud of its unified Puerto Rican identity, many shy away from accepting that bigotry and colorism are problems here the way they are for Black and brown Americans elsewhere in the U.S., Delgado says.

Growing up as a tan-skinned child in a part of western Puerto Rico where most people have European features, he says, “I never acknowledged racism.”

He especially regrets knowing so little about his late grandfather Albitt Soto-Mercado, a mixed-race Black man who was an advocate for Puerto Rican independence.

“Not having much that was passed down from generation to generation,” Delgado says, “I found myself trying to understand my grandfather and what it meant to be a Black man in Puerto Rico.”

As painful as it is to admit, he fears that he was complicit in a wrong made worse by his previous lack of racial understanding.

Half an hour east of San Juan is the coastal town of Loíza, the only majority Black city on the island.

Across the road from a beach with golden sand and turquoise water, Delgado greets Rafael Rivera at the kiosk where he sells fish, rice and peas and other island cuisine.

Biased policing and joblessness make life harder for residents here just as they do for the Black Americans Delgado encountered while attending college in Chicago.

Rivera doesn’t see much of an upside to Puerto Rico joining the union as a state.

“Because of how Black people in the U.S. are treated, I don’t believe it would be beneficial to us,” he says in Spanish as Delgado looks on.

“Before being an American, I’m a Puerto Rican,” says Rivera, 57.

And yet Puerto Rico has also failed its Black and brown residents, he says.

Baseless drug raids, harassment and violence at the hands of police officers are common complaints in Loíza. Rivera says he’s been wrongfully detained himself.

Locals see racism as the motive.

The immigration debate poses a moral dilemma for America.

Rivera says his city was the last place to get power and water service restored after Maria and recent earthquakes.

To compensate for the territorial government’s negligence, the local community council he heads has set up health clinics, a job center for the unemployed, a tutoring program for schoolchildren and a shelter for people uprooted by natural disasters.

Delgado looks stricken as he takes in Rivera’s stories.

“His struggle is my grandpa’s struggle, which makes it my struggle indirectly,” he says later.

“It left me wondering: Did he ever feel loved by his people?” Delgado says of his grandfather. “It’s heartbreaking — to have the citizenship of this nation and yet not be loved.”

Modesta Irizarry, a Loíza community leader who’s been helping to distribute food aid during the COVID-19 pandemic, is a mentor to Delgado. She says becoming a state would waste valuable resources for an island still climbing back from the largest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history.

The 62-year-old gives us a tour of her city, which was founded in the late 1800s by freed African slaves who migrated to this side of the island from sugar plantations in the west.

Loíza sits between two rivers that spill into the sea. Irizarry strikes a pose at the edge of one of the rivers, opening her arms wide. Despite the horrors their enslaved ancestors faced, locals believe they’re cradled by nature because of the distinctive location — and watched over by the Lord above.

In the small town square, a mostly Black congregation listens to a Catholic church service delivered in Latin as Irizarry, her teenage daughter and Delgado look on through the open doors.

Down an alleyway draped with bougainvillea, Irizarry stops at the house of painter and sculptor Samuel Lind, who’s dedicated his career to capturing the daily lives, struggles, beauty and Black cultural pride of Loíza’s residents.

Altars with candles and offerings to African ancestors fill the two-story studio and home.

Lind shows Delgado a painting that depicts justice as a Black woman holding a scale. Her eyes are left uncovered so she can bear witness to racism, and her tipped scale symbolizes the unfairness of America’s criminal justice system.

“It can’t be denied that there’s discrimination toward the people in Loíza until this day,” the 67-year-old artist says in Spanish. “But the thing is, when visitors come here, we are open to everyone because we know what it’s like to suffer from prejudice.”

Delgado seems enthralled with Lind’s depictions of a community that’s only a couple of hours from where he grew up, yet seems like a different Puerto Rico.

The Times’ Tyrone Beason journeyed from Charleston to Charlottesville to the inauguration in D.C. — on his way, reflecting on racism in a divided country.

Loíza is famous as a haven for the infectious, African-tinged dance called bomba. Locals consider it the dance of Black resistance, Lind says, an expression of joyful self-preservation in the face of oppression.

A wooden barrel drum sits among the easels upstairs. Lind sits down and taps out a bomba beat.

Irizarry smiles and claps her hands to the rhythm.

As sun rays break through storm clouds, Irizarry takes a stroll on the beach, where she often goes to clear her mind.

“Puerto Rico es Puerto Rico,” she says in Spanish as she watches a group of young people walk their horses in the crashing surf.

She’s content with the island maintaining its territorial status.

“We are part of the U.S., whether we’re a state or not,” she says.

More than anything, she wants her fellow American citizens up north to know that Puerto Ricans are strong and resilient.

“We are not people who are on our knees begging, as we are sometimes depicted,” she says.

Delgado disagrees with her stance on statehood but doesn’t argue.

“We are divided and we are conquered and we keep letting them conquer us,” he says later with a sigh. “It’s like we don’t know that we deserve more.”

Back in Old San Juan, gusty ocean winds batter the hurricane-damaged houses and cinder block bars of the working-class barrio made famous in the song “Despacito.”

High above on a street lined with pastel-colored buildings, dinner guests at the Gallery Inn gather under low-hanging chandeliers as a pianist plays classical covers of pop songs.

The hotel’s 86-year-old owner, Jan D’Esopo, a painter and sculptor with family ties to the island who moved here from the East Coast in 1961, has observed Puerto Rico’s ups and downs for decades.

She’s certain the statehood fight will go nowhere.

“My deceased husband, he always said, ‘Statehood? There’s too many Democrats here; the old boys’ll never let us in!’” D’Esopo says with a chuckle.

The “old boys” would be the Republicans.

“I think things are going to stay right the way they are,” D’Esopo says. “We all need to wise up.”

Delgado isn’t giving up.

He wants America’s leaders to see that if the citizens of U.S. territories are denied the rights and privileges granted to others, then democracy itself is an illusion.

“America has been a country for over 240 years, and we’re still having a conversation about equal rights,” he says.

“This is a matter of grabbing what’s ours.”

Delgado keeps an upside-down U.S. flag on a wall in his bedroom with the words “Decolonize P.R.” written on each white stripe to remind him of what he’s fighting for: a star on the flag that he’s certain Puerto Ricans, especially the most vulnerable among them, deserve.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.