Military leaders testify ‘strategic failure’ followed years of mistakes in Afghanistan

WASHINGTON — The nation’s top general testified Tuesday that the American war in Afghanistan ended in “strategic failure,” a grim conclusion that acknowledged a long series of mistakes and miscalculations by the Pentagon’s leaders.

“The enemy is in charge in Kabul,” Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark A. Milley said during a Senate Armed Services Committee hearing. “There’s no other way to describe that.”

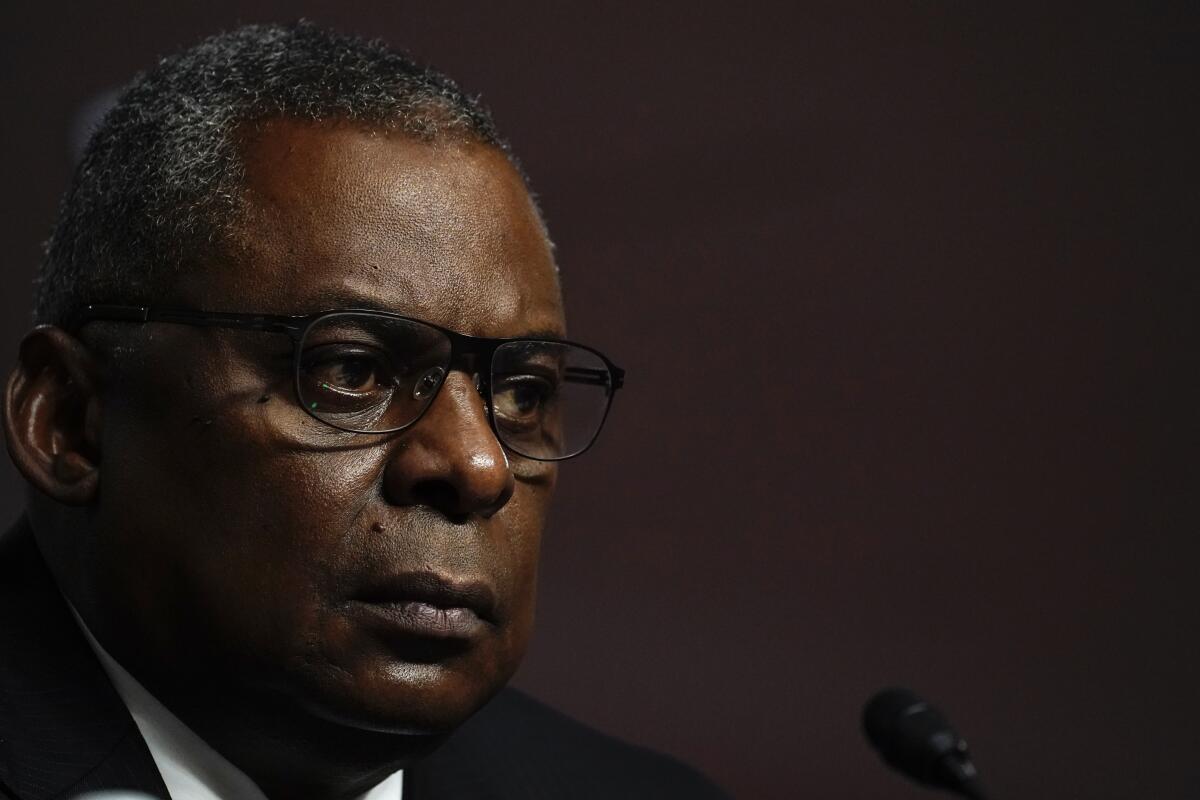

Defense Secretary Lloyd J. Austin III and Gen. Kenneth F. McKenzie Jr., who oversaw the most recent operations in Afghanistan, also testified at the hearing, which peeled back layer after layer of U.S. errors in judgment during the longest war in American history.

President Biden tries to turn the page on a foreign policy crisis with a speech about the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan.

U.S. military officials trained Afghan forces to be too dependent on advanced technology, did not appreciate the extent of corruption among local leaders, and didn’t anticipate how badly the Afghan government would be demoralized by the U.S. withdrawal, the Pentagon’s leaders told the committee. Taken together, they testified, such errors enabled the Taliban to swoop back into power far faster than U.S. officials had anticipated.

Intelligence reports suggesting the Afghan forces could hold off longer were “a swing and a miss,” Milley said.

The decision to pull out was originally made by President Trump, whose administration reached an agreement with the Taliban to withdraw U.S. troops by May 1, a little more than three months after he left office.

President Biden decided to move forward with a withdrawal, believing that it was no longer worthwhile to prop up the Afghan government, but he extended the deadline to Aug. 31.

Some of the testimony on Tuesday undermined Biden’s claims that military leaders did not not recommend leaving some troops in Afghanistan. McKenzie said he supported keeping 2,500 service members there, a recommendation that was made by Army Gen. Austin “Scott” Miller, who had commanded U.S. forces there from 2018 until July.

“I was present when that discussion occurred, and I am confident that the president heard all the recommendations and listened to them very thoughtfully,” he said.

McKenzie also said it was his belief that pulling out all U.S. troops “would lead inevitably to the collapse of the Afghan military forces and eventually the Afghan government.”

It was an unusually public airing of divisions between the president and military leaders — one that will probably reverberate throughout Washington as Biden continues to face political fallout over the chaotic and deadly withdrawal from Afghanistan.

White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki, addressing reporters as the hearing was underway, said “there was a range of viewpoints” presented to Biden during internal debates. She also said it was clear that leaving troops in the country would eventually cause the conflict to escalate, drawing U.S. forces back into fighting with the Taliban.

“The president was just not willing to make that decision,” Psaki said. “He did not think it was in the interests of the American people or the interests of our troops.”

During Tuesday’s hearing, Senate Armed Services Committee Chairman Jack Reed (D-R.I.) said lawmakers should resist the “temptation to close the book on Afghanistan and simply move on.”

“We must capture the lessons of the last two decades to ensure that our future counter-terrorism efforts in Afghanistan and elsewhere continue to hold violent extremists at bay,” he said.

Such operations in Afghanistan will be much more challenging now that there are no U.S. forces on the ground, McKenzie testified. He said the military still has the ability to “look into Afghanistan,” but in a more limited way.

Biden said the withdrawal marks the end of a failed era of nation-building. But the struggle to protect democracy and the rights of Afghans must continue.

“It is very hard to do this,” he said. “It is not impossible to do this.”

A reminder of how hard it can be to develop accurate intelligence came during the U.S. evacuation, which was bloodied by an Islamic State suicide bombing that killed 13 U.S. service members and scores of Afghan civilians. Fearing a second attack, the U.S. launched a drone strike against a car they believed was connected to terrorist operations.

“This time, tragically, we were wrong,” McKenzie testified. The airstrike killed 10 civilians, including seven children.

The committee’s top Republican, Sen. James M. Inhofe of Oklahoma, blamed Biden for the messy pullout.

“He failed to anticipate what all of us knew would happen,” Inhofe said. “So in August, we all witnessed the horror of the president’s own making.”

Austin, however, described the flawed operation as ultimately successful. U.S. officials had expected to evacuate no more than 80,000 people, he said, but 124,000 were flown to safety.

“Was it perfect? Of course not,” the Defense secretary said, adding that it nevertheless “exceeded expectations.”

Afghanistan wasn’t the only topic covered during the hearing. At one point, Milley defended his phone calls with his Chinese counterpart near the end of Trump’s presidency, saying the conversations were his responsibility in order to prevent a potentially deadly misunderstanding between two superpowers.

During the calls, which occurred before and after the November election, Milley assured Gen. Li Zuocheng, the top Chinese commander, that Trump was not planning a surprise attack. The discussions were revealed in “Peril,” a new book by Bob Woodward and Robert Costa.

Trump has suggested that Milley committed treason, and Republicans have said he might have subverted the chain of command.

But Milley testified that his calls with Li were far from secret. He said that he coordinated the discussions with Pentagon leadership and that afterward he briefed Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo and White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows.

Bob Woodward’s third book on the Trump presidency, written with Robert Costa, (overly) details the Trump-Biden transition with little new insight.

In addition, Milley testified that he wasn’t undermining Trump because the president had no intention of attacking China. He said he was concerned that Chinese intelligence was mistakenly concerned that a strike was in the works.

“My task at that time was to de-escalate,” Milley said. “My message again was consistent — ‘Stay calm, steady, and de-escalate. We are not going to attack you.’”

Milley also described a call with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco) after the Jan. 6 assault on the U.S. Capitol. Pelosi expressed concerns that Trump was unstable, and she worried about his control of the country’s nuclear weapons, according to “Peril.”

The general told lawmakers that as a military advisor, he’s not in the “chain of command” for a nuclear strike, but he is in the “chain of communication.”

During his conversation with Pelosi, Milley testified, he said that “the president is the sole nuclear launch authority, and he doesn’t launch them alone, and I am not qualified to determine the mental health of the president of the United States.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.