Former federal prosecutor charged in Durham’s Russia inquiry with making false statement to FBI

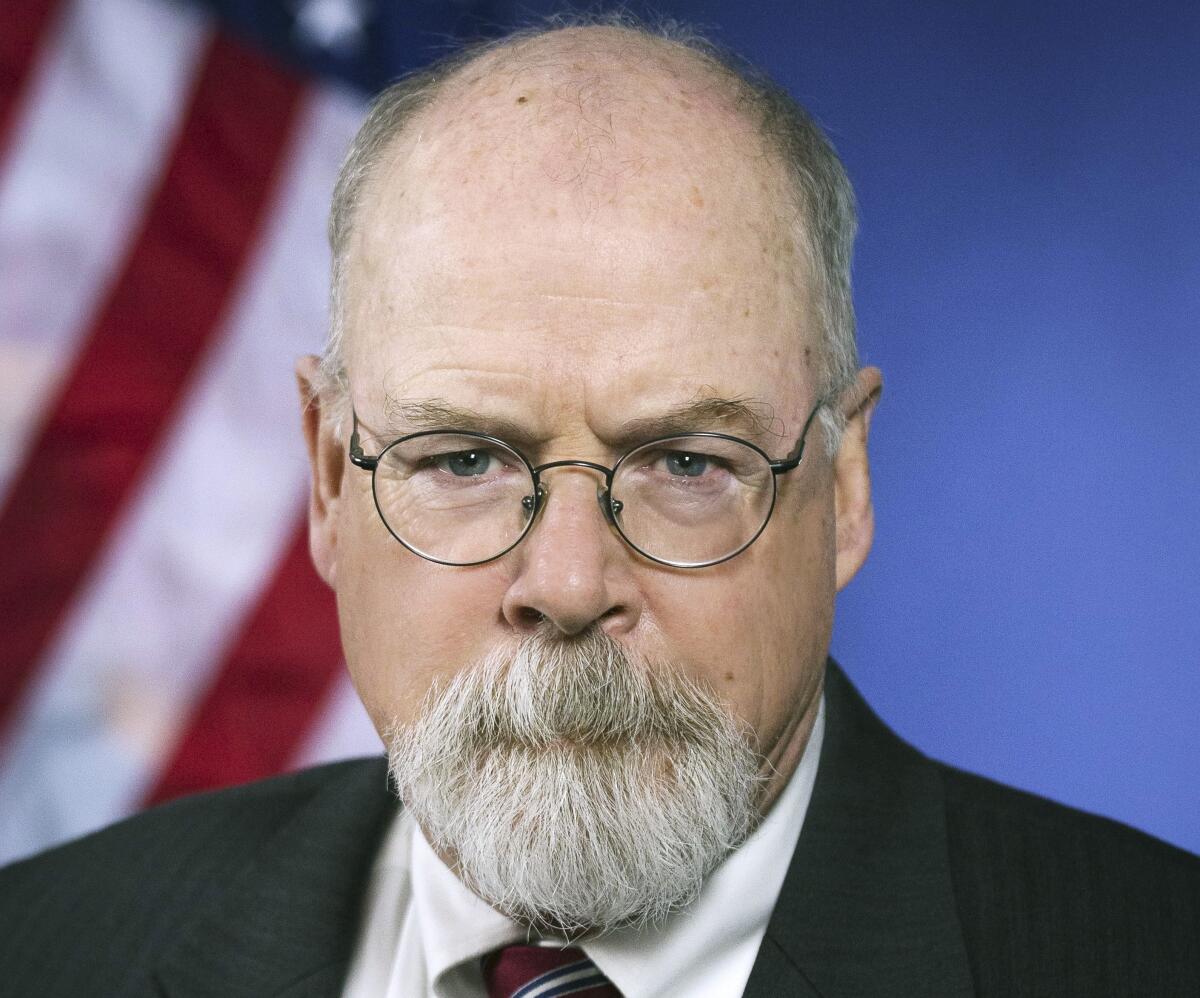

WASHINGTON — The prosecutor tasked with examining the U.S. government’s investigation into Russian election interference charged a prominent cybersecurity lawyer on Thursday with making a false statement to the FBI.

The indictment accuses Michael Sussmann of hiding that he was working with Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign during a September 2016 conversation he had with the FBI’s general counsel, when he relayed concerns from cybersecurity researchers about potentially suspicious contacts between Russian-based Alfa Bank and a Trump organization server. The FBI looked into the matter but found no evidence of a secret back channel.

That deception mattered because it “deprived the FBI of information that might have permitted it to more fully assess and uncover the origins of the relevant data and technical analysis, including the identities and motivations of Sussmann’s clients,” according to the indictment filed by special counsel John Durham and his team of prosecutors.

Sussmann’s lawyers said their client was charged because of “politics, not facts.”

“The Special Counsel appears to be using this indictment to advance a conspiracy theory he has chosen not to actually charge. This case represents the opposite of everything the Department of Justice is supposed to stand for. Mr. Sussmann will fight this baseless and politically-inspired prosecution,” attorneys Sean Berkowitz and Michael Bosworth said in a statement.

The case against Sussmann is the second prosecution brought by Durham in 2½ years of work. Both involve false statements, yet neither undoes the core finding of an earlier investigation by special counsel Robert S. Mueller III that Russia had interfered in sweeping fashion on behalf of Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign and that the Trump campaign welcomed that aid.

The indictment also lays bare the wide-ranging and evolving nature of Durham’s investigation. In addition to having scrutinized the activities of FBI and CIA officials during the early days of the Russia inquiry, it also has looked at the behavior of private individuals such as Sussman, who provided the U.S. government with information as it scrambled to determine whether Trump associates were coordinating with Russia to tip the election’s outcome.

The indictment concerns a Sept. 19, 2016, meeting at FBI headquarters between Sussmann and the FBI’s then-general counsel, James Baker. During the meeting, prosecutors say, Sussmann provided Baker with three “white papers” and data files that purported to show a potential connection between Russia-based Alfa Bank and a Trump Organization server.

According to the indictment, Sussmann said he was not presenting the materials on behalf of any particular client, which prosecutors say led Baker to believe that Sussmann was acting as a “good citizen” rather than a “paid advocate or political operative.”

Sussmann’s attorneys say he met with Baker because a major news organization was about to publish a story about Alfa Bank, and he wanted to give Baker a copy of the material on which the story would be based. Besides, they say, it didn’t matter who Sussmann’s clients were because the FBI would presumably have looked into the issue whether there was a political connection or not.

The Alfa Bank matter was not a pivotal element of the Russia inquiry and was not even mentioned in Mueller’s 448-page report in 2019. Still, the indictment may give fodder to Russia investigation critics who regard it as politically tainted and engineered by Democrats.

Sussmann’s former firm, Perkins Coie, has deep Democratic connections. A then-partner at the firm, Marc Elias, brokered a deal with the Fusion GPS research firm to study Trump’s business ties to Russia. That work, by former British spy Christopher Steele, produced a dossier of research that helped form the basis of flawed surveillance applications targeting a former Trump campaign official, Carter Page.

A spokesman for Perkins Coie said Sussmann, “who has been on leave from the firm, offered his resignation from the firm in order to focus on his legal defense, and the firm accepted it.”

The Durham investigation has already spanned months longer than the earlier special counsel inquiry into Russian election interference conducted by Mueller, the former FBI director, and his team. Durham’s investigation was slowed by the COVID-19 pandemic and experienced leadership tumult following the abrupt departure last fall of a top deputy on Durham’s team.

Though Trump had eagerly anticipated Durham’s findings in hopes that they’d be a boon to his reelection campaign, any political impact the conclusion may have once had has been dimmed by the fact that Trump is no longer in office.

The Durham appointment by then-Atty. Gen. William Barr in 2019 was designed to examine potential errors or misconduct in the U.S. government’s investigation into whether Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign was conspiring with Russia to sway the outcome of the election.

A two-year investigation by Mueller established that the Trump campaign was eager to receive and benefit from Kremlin aid, and documented multiple interactions between Russians and Trump associates. Investigators said they did not find enough evidence to charge any campaign official with having conspired with Russia, though half a dozen Trump aides were charged with various offenses, including false statements, and several were convicted.

Until now, Durham had brought only one criminal case — a false-statement charge against an FBI lawyer who altered an email related to the surveillance of Page to obscure the nature of Page’s preexisting relationship with the CIA. That lawyer, Kevin Clinesmith, pleaded guilty and was sentenced to probation.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.