Frenemies no more. Harris stumps for Newsom as the Californians’ political interests align

WASHINGTON — They’ve been described as frenemies, allies and something in between — a pair of Democratic stars from San Francisco whose parallel ascents always seemed at risk of colliding.

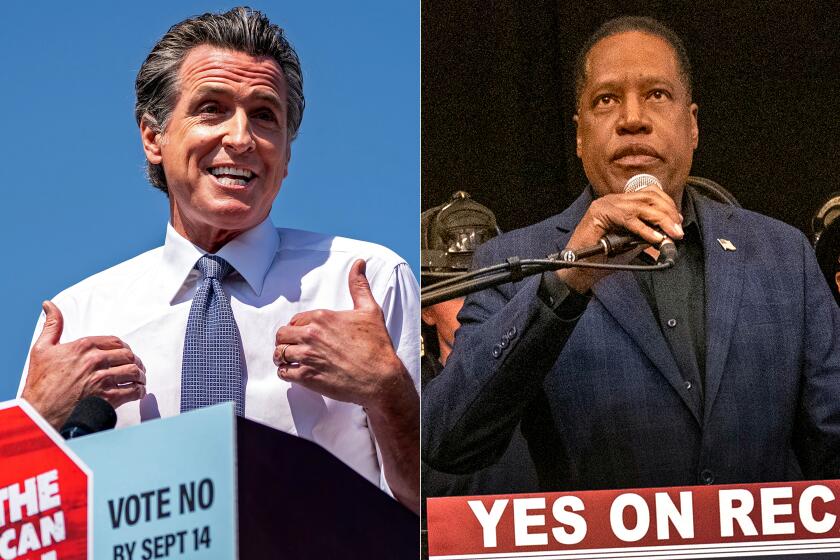

As Vice President Kamala Harris traveled to California to rally for Gov. Gavin Newsom on Wednesday, their political interests appear to have aligned.

A Newsom defeat in next week’s recall election would pose a significant problem for the Biden administration. It would put a Republican governor in charge of the biggest and arguably most progressive state — demoralizing Democrats ahead of the 2022 midterm elections when their party already faces gale-force headwinds. And it would allow that Republican governor to appoint a GOP replacement if Sen. Dianne Feinstein, the San Francisco Democrat who is 88, retires or falls ill.

That doesn’t mean the competitive juices between Harris and Newsom have evaporated. “She may be getting a bit of amusement watching him suffer,” said a San Francisco Democrat who requested anonymity to discuss the pair’s fraught relationship.

“But, she doesn’t want to see a Gov. [Larry] Elder or California’s junior senator being Tom McClintock, or whoever it would be,” the Democrat added, referring to two conservative GOP politicians, one leading the field of Republican candidates in the recall and the other an influential member of Congress who could presumably replace Feinstein.

The Harris-Newsom story began in 2003 in San Francisco when Harris was elected the city’s top local prosecutor and Newsom its mayor. They were young — both were under 40 — and ambitious, and had a coterie of overlapping friends, donors and advisors.

Brian Brokaw, who held senior positions in three statewide campaigns for Harris and is helping Newsom fight the recall, said he, like others, has used the term “frenemy” to describe the relationship “but I don’t think that actually captures the reality of it.”

“They were political siblings who were reared in the same 7-mile by 7-mile fishbowl of San Francisco politics, had many of the same mentors, had many of the same donors, had much of the same base of support, were elected on the same ballot,” he said.

Politics, especially in those early San Francisco years, could feel like family affairs — with everyone bumping into each other at political events and fundraisers. At one gala, according to Politico, Harris and Newsom engaged in a friendly bowling competition with charity centerpieces — large orbs of ice.

That small universe could also lead to family tension. Newsom’s wife at the time, Kimberly Guilfoyle, once accused Harris of blocking her from getting a job at the district attorney’s office. Guilfoyle went on to become a Fox News personality who dates Donald Trump Jr. and advises his father, the former Republican president.

Newsom got an early leg up in their political rivalry. He was the first to make national headlines in San Francisco, using his mayoral office to issue marriage licenses to gay couples in defiance of state law. They continued their upward trajectory, with Harris rising to state attorney general and Newsom becoming lieutenant governor.

An inflection point came in 2015, when Sen. Barbara Boxer announced she would not seek reelection. There was enormous political pressure for one to run for the open Senate seat, though both were known to harbor ambitions for the governorship.

“It was a game of chicken, I think, to see who would make the move first,” said a former Harris advisor.

Harris blinked, deciding it made more sense to run for Senate, where she could model her career on the party’s growing wing of progressives, giving Newsom an opening to run for governor in 2018.

The two politicians endorsed each other for various jobs, including Harris’ brief run for president. And they appeared together at important occasions and vied to represent similar versions of the Democratic Party’s future. They both realized they had little to gain by challenging each other in public, even if friends have said Newsom appeared to have derived pleasure from Harris’ failed presidential bid and Harris seems to be amused by Newsom’s recall plight.

“If there was a rivalry, and I don’t have that much doubt that there was, over time they reached an accommodation,” said Dan Morain, a longtime state political reporter who wrote a biography of Harris.

In April, they exchanged smiles and wonky banter about infrastructure, when Harris toured a water treatment facility in Oakland during her first official visit to the state as vice president. In her public remarks that day, Harris praised Newsom effusively, as “a real champion in California and outside of California on California priorities.”

By then, it was clear Newsom would be facing a recall election and Harris, trying to keep the Biden administration’s agenda on track, would need him to stay in his job. As Harris spoke in San Leandro for Newsom on Wednesday — extolling “my dear friend, my longstanding friend” — polls showed him in strong position to keep his job.

“There was this media-driven narrative that formed over the years that inevitably they were going to come to a head and there would be this battle of all battles over who would get the keys to the kingdom,” said Brokaw, the political advisor. “It’s worked out pretty well for both of them.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.