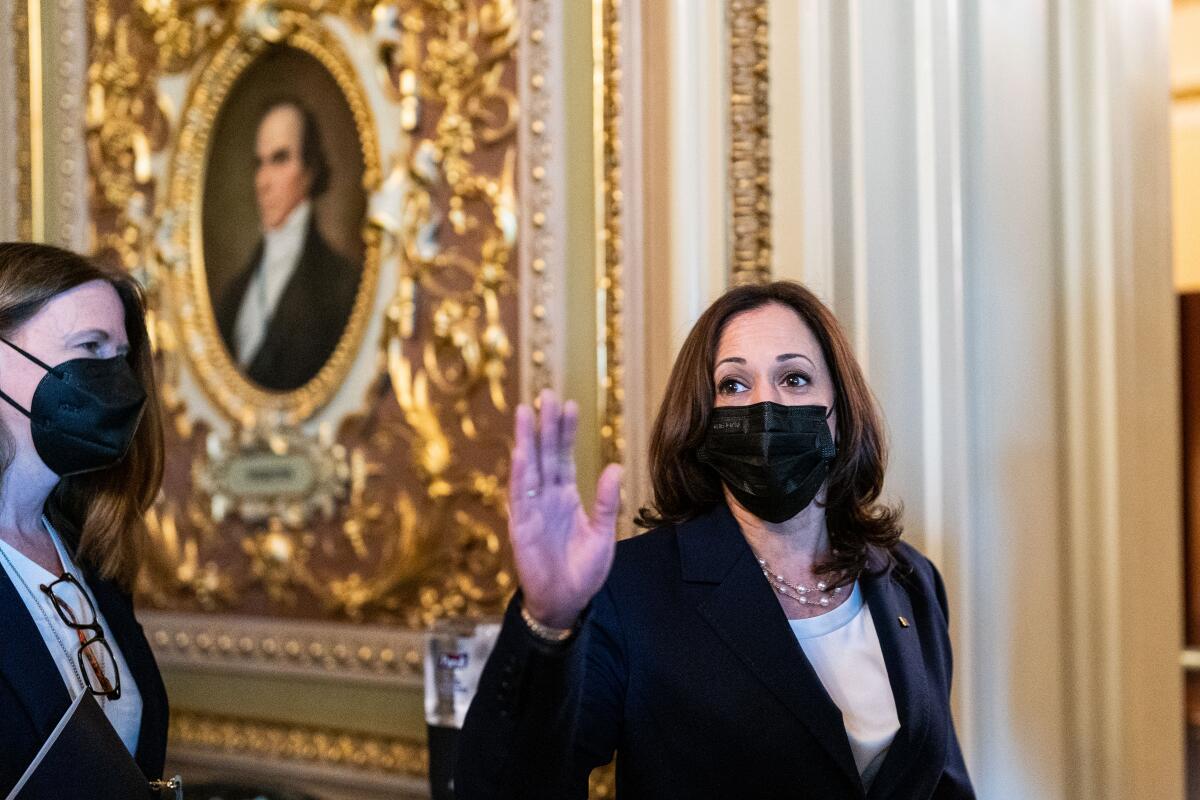

Kamala Harris heads to Vietnam while Afghanistan chaos rekindles the past

WASHINGTON — Vice President Kamala Harris will arrive next week in Vietnam at a moment when many Americans are again debating the final hours of the war there — with some comparing the recent chaos in Afghanistan to the fall of Saigon in 1975, when Americans frantically fled the U.S. Embassy by helicopter.

Biden administration officials did not anticipate the debacle in Afghanistan when they started planning Harris’ trip to Singapore and Vietnam, her second foreign journey as vice president, and they bristle at the comparisons.

But in some ways, analysts and experts say, the timing of the trip allows the United States to reassert its stature in the region at a moment when its reputation as a world power has been battered elsewhere.

Southeast Asia is a linchpin in America’s global competition with China, and leaders in the region have been impatient with the Biden administration’s failure to deliver more COVID-19 vaccines and the generally slow pace of high-level engagement with top U.S. officials. President Biden, for example, has yet to call leaders from any Southeast Asian country.

Vietnam, after years of estrangement, has become a popular destination for American presidents, who are generally greeted warmly, regardless of political party. Harris, whose mother was born in India, is the first American vice president and the highest-ranking American leader of Asian descent to visit Vietnam.

The Biden administration “spent the first six months really getting the crap kicked out of them” in the Southeast Asian press, with pundits condemning the U.S. president’s seeming indifference, said Greg Poling, a Southeast Asia specialist at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a nonpartisan think tank.

That began to change late in recent months. In July, Defense Secretary Lloyd J. Austin III traveled to Singapore, Vietnam and the Philippines, and early this month Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken attended a virtual summit of Southeast Asian officials. Harris’ trip is meant to build on that momentum, though the exclusion of Indonesia, the world’s third-largest democracy, from her itinerary has prompted griping there among opinion leaders.

Administration officials, speaking on the condition of anonymity, conceded that Harris considered postponing the visits as the situation in Afghanistan deteriorated, with the Taliban this week cementing its takeover of a country where the U.S. has been at war for two decades.

The Harris team decided to go ahead, in part, to rebut criticism that Biden’s withdrawal from Afghanistan signaled a retreat from his promise to revamp America’s global role following four years of President Trump antagonizing allies with his “America first” agenda. During the weeklong trip, the administration officials said, the vice president will keep close tabs on the situation in Afghanistan, where the U.S. military is scrambling to evacuate thousands of Americans and Afghans who assisted in the war effort.

“It’s always good for senior U.S. officials to visit Southeast Asia,” said Matt Pottinger, a China specialist who served as Trump’s deputy national security advisor. “These are countries that are nervous about China’s rising shadow.”

Harris is scheduled to leave Washington on Friday and arrive late Saturday in Singapore, a small but bustling island nation where the U.S. maintains an important naval base and where a variety of multinational companies — including Facebook and Google — maintain their Asian headquarters. The country is just beginning to emerge from a strict COVID-19 lockdown.

Singapore is eager to cooperate more on climate change and digital regulation with the U.S. but, like other countries in the region, wants to balance its American relationship with China, which is rapidly expanding its economic and military influence.

Harris will spend three days there, meeting government and business leaders and American sailors serving on the U.S. warship Tulsa. She will also deliver a broad foreign policy speech intended to lay out the administration’s vision for the region.

She will then fly about 1,400 miles to Hanoi, where her meetings with leaders will focus more on the pandemic, including a ceremony to open a regional office of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vietnamese leaders are likely to press Harris about U.S. efforts to deliver more vaccine doses. In Singapore, a global business capital, about three-fourths of the population is vaccinated. But Vietnam is one of many countries in the region that has been struggling with low access to vaccines and high rates of infection.

She will return to the United States on Thursday, stopping in Hawaii to refuel and speak with troops at Pearl Harbor. Rather than return to Washington, Harris plans to spend time in San Francisco, where she is expected to campaign for Gov. Gavin Newsom as he fends off a potential recall, an administration official said.

Harris undoubtedly hopes the visits will assist in erasing memories of her first foreign trip, to Guatemala and Mexico, when she was criticized at home by conservatives and some liberal activists for comments about immigration and the U.S.-Mexico border. But she may not get much attention for this trip outside Asia, with a 12-hour time difference on the East Coast and international interest fixed on Afghanistan and a devastating earthquake in Haiti.

COVID-19 restrictions will also limit her events and restrict the number of reporters covering them. While President Obama famously dined with the late Anthony Bourdain at a simple Hanoi noodle shop — a goodwill gesture that only enhanced his popularity in the country — Harris is not expected to participate in any cultural diplomacy.

Harris is likely to still get attention in the local press in both nations, particularly in Vietnam. The country has been locked down for months amid a surge of coronavirus cases, and its leaders and citizens are eager to receive a high-level visitor, said Thomas Vallely, the director of the Vietnam program at Harvard University’s Kennedy School.

The country is “in a crisis and all of the sudden someone’s coming,” Vallely said, adding that Harris’ Vietnam stop will be “the most significant trip [there] of any American official since Bill Clinton,” who opened diplomatic relations with the country in 1995.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.