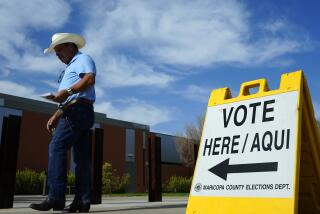

Supreme Court limits Voting Rights Act in ruling for Arizona Republicans

WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court’s conservative majority limited the reach of the Voting Rights Act on Thursday and ruled that states may enforce election rules even if they have a more discriminatory effect on Black, Latino or Native American voters.

In a 6-3 decision, the justices upheld two Arizona rules that were sponsored by Republicans and opposed by Democrats. One calls for throwing out legal ballots that were cast in the wrong precinct. Arizona discards a higher percentage of ballots than any other state because of its shifting precinct boundaries.

The justices also upheld a second law that makes it a crime for anyone other than family members or postal workers to deliver a mail ballot, a rule that has a significant effect on tribal reservations.

The Arizona case took on major importance this year because it came amid a partisan national battle over voting rights and election rules — and because the Supreme Court has said remarkably little to clarify at what point state election rules become so strict that they may interfere with the right to vote.

In the end, the justices divided along partisan lines. The six Republican appointees voted to uphold Arizona’s Republican-backed rules, while the three Democratic appointees agreed with Democrats who sued to challenge the voting restrictions.

Writing for the court, Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. said that voting in Arizona was “equally open” to all eligible voters and that “mere inconvenience cannot be enough to demonstrate a violation” of the Voting Rights Act.

He acknowledged that the “out-of-precinct” policy resulted in discarding twice as many ballots from minority voters as white voters. But he said the overall effect of the rule was modest.

Alito also dismissed Democrats’ argument that even if votes regarding local races were discarded because they were cast in the wrong precinct, other votes on the same ballot should be counted in races in which location did not matter, such as for president or governor. Alito said the law did not require this.

The court’s three liberal justices dissented. They said Congress had amended the Voting Rights Act to forbid election rules that “result in” discrimination against minority voters.

“What is tragic here is that the court has (yet again) rewritten — in order to weaken — a statute that stands as a monument to America’s greatness, and protects against its basest impulses,” Justice Elena Kagan wrote in dissent.

The court has freed Texas and other Southern states to add voting restrictions, and has given the GOP an edge in the battle to control Congress.

UC Irvine law professor Rick Hasen, an expert on election law, said the ruling has “severely weakened” the Voting Rights Act just as Republican-led states, including Arizona, are passing restrictive new voting laws. Combined with earlier rulings, “the conservative Supreme Court has taken away all the major available tools for going after voting restrictions,” he said.

President Biden said he was “deeply disappointed in today’s decision … that undercuts the Voting Rights Act. In a span of just eight years, the court has now done severe damage to two of the most important provisions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 — a law that took years of struggle and strife to secure.”

He said the decision “makes it all the more imperative to continue the fight” for new voting rights measures in Congress.

Janai Nelson, a lawyer for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, said “the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was once our country’s most effective federal civil rights legislation, won on the backs of civil rights leaders and allies determined to gain unfettered access to the ballot box for Black Americans. Today’s decision dealt a substantial blow to what was left of the act following the court’s Shelby County decision, which effectively invalidated the other core part of the statute.”

Alito’s opinion will make it harder for civil rights lawyers and the Justice Department to challenge new restrictive rules on voting because they are based on racial bias or because they would have a discriminatory effect on Black or Latino voters.

Thursday’s opinion undercuts both lines of argument. Alito said election rules are not illegal as long as minorities still have an opportunity to vote. He said, for example, that if voters do not know their precinct, they could vote by mail.

And he said that sometimes what looks like racial bias may be just partisanship.

The district judge who initially heard the Arizona case found that Republican lawmakers were spurred to enact the criminal ban on collecting mail ballots after they watched a false and “racially tinged” video of a “thug” delivering a bag to a postal center, supposedly stuffed with ballots. A Republican senator warned that such unsavory characters were collecting ballots from Mexican Americans.

The 9th Circuit Court of Appeals cited this incident as evidence the Arizona law was motivated by racial bias.

But Alito discounted it. “The spark for the debate over mail-in voting may well have been provided by one senator’s enflamed partisanship, but partisan motives are not the same as racial motives.” Moreover, there is “no evidence that the legislature as a whole was imbued with racial motives,” he said.

Last week, the Justice Department sued Georgia over its new voting restrictions and contended the legislation was motivated by a discriminatory purpose. Thursday’s decision suggests that specific evidence of racial bias may not be enough to prove the legislation had an illegal discriminatory purpose.

The Justice Department will file a lawsuit challenging a Georgia voting law that the attorney general says discriminates against Black voters.

The 9th Circuit had said last year that Arizona discarded far more ballots than any other state by redrawing its precincts often and by canceling all votes cast in the wrong place. In nearly all cases, these out-of-precinct voters were legally entitled to vote for a candidate for U.S. senator, U.S. representative, governor or president who appeared on the ballot.

In its defense, Arizona argued that half of the states had laws that require voters to cast their ballots in the right precinct. California is not among them.

Eight years ago, the conservative justices in a 5-4 opinion threw out the part of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that imposed federal oversight on states with a history of discriminating. Arizona was among them.

After that ruling, in Shelby County vs. Holder, states including Georgia, Texas and Arizona were free to adopt new election rules without preapproval from the Justice Department in Washington.

They could still face discrimination lawsuits under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which applies nationwide. But exactly what constitutes discrimination under the law has been unclear.

In 1982, Congress amended the law with a bipartisan compromise to say it did more than forbid intentionally racist rules. Rather, the law also forbids states and localities from imposing any voting rule or procedure that “results in a denial or abridgment of the right … to vote on account of race.”

In recent decades, this part of the law has been used to challenge state election maps whose districts have been drawn in a way that’s made it hard for Black and Latino candidates to be elected. But the Supreme Court had not spoken on how the law applies to voting rules.

The Democratic National Committee sued over the two Arizona provisions that it said resulted in discrimination. Its lawyers alleged the “wrong precinct” rule resulted in discrimination against Latino voters in the Phoenix area who moved more often. In some areas, more than 40% of the voters had their precinct changed in the two years between elections.

The Democrats also alleged the criminal ban on so-called ballot harvesting had a discriminatory effect on Navajos and other Native Americans who lived on reservations with poor mail service.

They lost before a federal judge and a three-judge panel of the 9th Circuit but won before an 11-member group of the appeals court.

In a 7-4 decision, the appeals court said Arizona had by far the nation’s highest percentage of ballots discarded because they were cast in the wrong precinct. And it said Latino, Black and Native American voters were more than twice as likely as white voters to have their otherwise legal ballots thrown out.

The appeals court also described Arizona’s history of discriminating against Latino and Native American voters. Its opinion noted that an earlier version of its criminal ban on “ballot collection” had been blocked as discriminatory under the Voting Rights Act but was revived after the Supreme Court’s ruling, which lifted the “pre-clearance” rule.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.