Virginia Democrats pick Terry McAuliffe as nominee for governor, setting the stage for a bellwether election

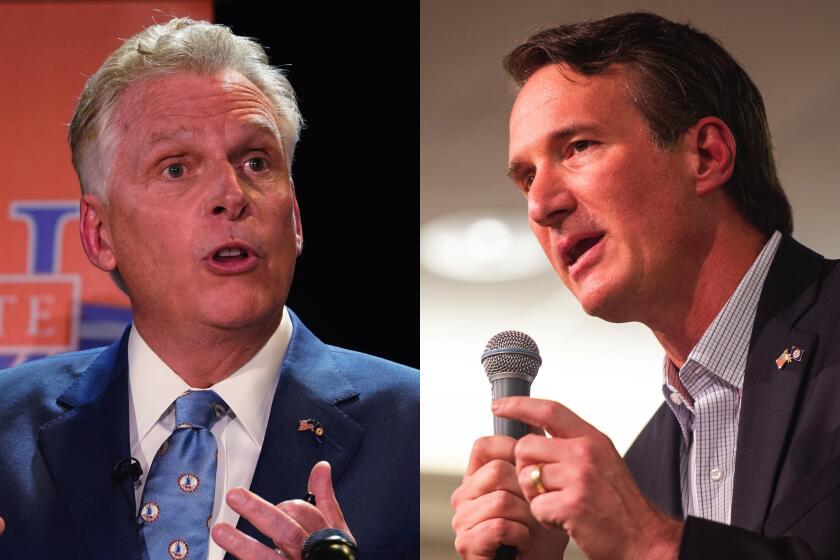

WASHINGTON — Virginia Democrats chose Terry McAuliffe to be their nominee for governor Tuesday, setting the stage for one the biggest electoral tests of strength between the parties since President Biden ousted Donald Trump from the White House.

McAuliffe, a former governor trying to make a comeback, built on a big fundraising advantage and easily won the state’s primary, beating four Democratic rivals who vied to succeed Gov. Ralph Northam.

Now McAuliffe takes on GOP nominee Glenn Youngkin, a former private equity executive who has been endorsed by former President Trump.

Virginia race, coming a year after Biden won on a wave of anti-Trump sentiment, will test the parties’ strength ahead of the 2022 midterm election.

Buoyed by great personal wealth that could supplement his fundraising, Youngkin has already been attacking McAuliffe, portraying him as Biden’s ally in steering the country too far to the left. In turn, McAuliffe is tagging Youngkin as an apostle of Trumpism.

The off-year election will be watched nationally as a political bellwether heading into the midterm election of 2022, a window onto how the parties fare without Trump on the ballot as a galvanizing force for both his friends and foes.

Virginia race, coming a year after Biden won on a wave of anti-Trump sentiment, will test the parties’ strength ahead of the 2022 midterm election.

Virginia has been trending Democratic in recent years, but Republicans believe they have a chance in 2021 because history is on their side: The commonwealth’s gubernatorial contest is almost always lost by the party that holds the White House.

The Democratic primary offered voters a choice between elevating a new generation of leadership, including two Black women running for governor, or going with an older, familiar white political figure who once headed the Democratic National Committee, and has been portrayed as the safest bet to win in November. Democrats nationally faced a similar choice in the 2020 presidential primary, when they chose Biden over a diverse field of younger candidates largely because he was seen as the most electable.

“I know how to defeat Republican extremists like Glenn Youngkin,” McAuliffe said Monday on Twitter. “I’ve done it before and I’ll do it again.”

McAuliffe’s strongest opponents were state Sen. Jennifer McClellan and former state Delegate Jennifer Carroll Foy. Their supporters had hoped that, with one of them as the nominee, Virginia could have made history this fall by selecting the nation’s first female Black governor.

Also running were progressive state Delegate Lee Carter, and Lt. Gov. Justin Fairfax — who might have been a leading contender and could also have been the state’s second Black governor had he not been confronted with sexual assault allegations, which he strongly denied, maintaining the relations were consensual.

McAuliffe’s rivals argued that the commonwealth’s leadership needs new blood, and warned that McAuliffe would not generate the voter enthusiasm and high levels of turnout that will be needed to beat the well-funded GOP nominee and keep the state Legislature in Democratic hands.

“If we want something different, we gotta do something different,” said Carroll Foy at a church in Hampton Roads on Sunday.

McClellan, at the candidates’ final debate in Newport News last week, said Democrats needed “a nominee who will excite and expand” the base of the party.

“It’s not enough to give someone something to vote against,” McClellan said.

But McAuliffe was the front-runner from the start. He served as Virginia’s governor from 2014 to 2018, then left office because of the commonwealth’s ban on anyone serving more than one consecutive term.

He campaigned this year as if he is seeking a second term, touting his record of overseeing economic growth, restoring voting rights for many felons and vetoing conservative social policies approved by the state Legislature, then controlled by Republicans. He was endorsed by Northam.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.