Biden wanted policing changes by the anniversary of George Floyd’s death. He’s still waiting

WASHINGTON — Soon after the police officer who killed George Floyd was convicted of murder, President Biden called Floyd’s relatives with a promise: Once he could sign legislation named for Floyd to change policing nationwide, he would fly them to Washington for the occasion.

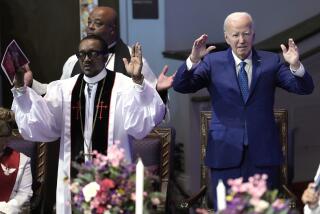

Floyd’s family visited the White House on Tuesday, the anniversary of his death, but there was no bill-signing ceremony. Bipartisan negotiations on Capitol Hill have yet to produce a breakthrough, a reminder of the steep hurdles that Biden faces as he confronts the country’s entrenched racial problems and its political polarization.

So the visit became an opportunity for legislative lobbying.

“If you can make federal laws to protect the bird which is the bald eagle, then you can make federal laws to protect people of color,” one of Floyd’s brothers, Philonise Floyd, told reporters after meeting with Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris. Two other brothers and a nephew similarly pleaded briefly for Congress to act.

Biden issued a statement promising to keep pushing for legislation, saying, “We face an inflection point.”

“The battle for the soul of America has been a constant push and pull between the American ideal that we’re all created equal and the harsh reality that racism has long torn us apart,” the president said. “At our best, the American ideal wins out. It must again.”

Allies similarly seized on the anniversary to press for addressing racism and policing at the national level. The Floyd family met with House members at the Capitol before going to the White House, and afterward were headed back to speak with the lead Senate negotiators on the bill — Democratic Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey and Sen. Tim Scott of South Carolina. Both men are Black and Scott is the only Black Republican in the Senate.

“If we cannot make progress on this issue in this environment, I question when we ever will be” able to, said Rep. James E. Clyburn of South Carolina, the highest-ranking Black member of Congress as the No. 3 House Democratic leader.

A year George Floyd’s murder, Black Lives Matter has achieved mainstream recognition. But the movement must now move beyond recognition toward concrete solutions.

When Biden declared victory over President Trump after November’s election, he said he had won a mandate “to achieve racial justice and root out systemic racism in this country.” He marked a rare moment of progress last week when he signed legislation to address hate crimes against Asian Americans, which have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic because the coronavirus was first detected in China.

“Every time we’re silent, every time we let hate flourish, you make a lie of who we are as a nation,” Biden said at last week’s bill-signing event. He said the law, which passed with bipartisan support, was the “the first significant break” since he took office in a racially fraught moment for the nation.

But getting the next break is proving difficult. Lawmakers are struggling to agree on legislation for nationwide policing changes that could ban chokeholds, set standards for using force and withhold federal funding to local law enforcement agencies that don’t comply.

The sticking point remains “qualified immunity,” a legal precedent that generally insulates police from civil lawsuits for their actions on the job. Republicans have resisted sweeping away or altering that protection.

George Floyd’s killing at the hands of police transformed lives around the world, but nowhere as profoundly as in the city where it occurred.

Biden had set Tuesday as a goal for passing legislation, to mark the anniversary of the killing of Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man who died in a Minneapolis street, his neck pinned for 9½ minutes under the knee of Derek Chauvin, a white police officer.

Although Congress didn’t meet that deadline, signs suggest a deal could be reached in the near future.

“We will get this bill on President Biden’s desk,” Rep. Karen Bass of Los Angeles, the lead House Democratic negotiator on the bill, pledged after a meeting with Floyd’s family on Capitol Hill on Tuesday.

“What is important is that, when it reaches President Biden’s desk, that it’s a substantive piece of legislation,” Bass, former chair of the Congressional Black Caucus, said. “And that is far more important than a specific date. We will work until we get the job done. It will be passed in a bipartisan manner.”

White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki said Tuesday that Biden remained in close touch with negotiators while “respecting the space needed” for them to find common ground. “We are continuing to press in the way that we feel is most effective and most constructive,” she said.

Benjamin Crump, a lawyer for Floyd’s family, said Biden didn’t want negotiators to move too fast just to make the deadline he’d set.

“He said he doesn’t want to sign a bill that doesn’t have substance and meaning,” Crump said. “So he is going to have patience to make sure it’s the right bill, not a rushed bill.”

Clyburn, in an interview Monday, said he remained optimistic, and he praised Biden for his commitment to addressing racism.

“We’ve got a president who is sensitive to these issues, a president who has a head and a heart,” he said. “We just finished four years of a heartless presidency.”

Underscoring Biden’s focus, the White House said Tuesday that the president would visit Tulsa, Okla., on June 1 to mark the 100th anniversary of the city’s race massacre.

Democrats and Republicans agree changes are needed to the legal doctrine but not how to do it.

Cornell Belcher, a Black pollster who worked to elect Barack Obama, the first Black president, said Biden had gone further than his predecessors to address racism.

“Understanding someone’s pain and someone’s story isn’t symbolism. It’s, in fact, the key to leadership,” Belcher said. “What is fundamentally different about this administration than any other administration in my lifetime is that no other administration has so openly talked about systemic racism and put plans in place across this administration, across the Cabinet, to, in fact, take on systemic racism.”

Belcher also said that hosting Floyd’s relatives offers Biden a political opportunity to increase pressure on Republicans, including Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, to reach a deal.

“The opportunity for Biden is to say, ‘Look, I’d hoped to have you here because I’d hoped there’d be a signing ceremony for justice and policing, but we can’t do that because Mitch McConnell and Republicans in the Senate have dug in,’” Belcher said. “He can and should pivot to the conversation politically about why what the vast majority of Americans want to happen is not happening.”

Belcher and some other Democratic pollsters say that singling out Republicans for blocking Biden’s broadly popular agenda could keep the Democratic Party’s core voting blocs, including Black and younger voters, energized and active heading into the 2022 midterm election.

“The lack of movement on signature issues could actually help in creating higher turnout and more engagement if it’s communicated the right way,” said John Della Volpe, the polling director at Harvard’s Institute of Politics, who advised Biden’s campaign last year on outreach to younger voters.

He pointed to Biden’s remarks in Philadelphia after Floyd’s death, when he called on the country to work to eradicate systemic racism. Biden called it “the work of a generation” and warned that it would take longer than a presidential term. If younger voters believe that the president and his party are engaged on racial justice issues, even if progress is slow, “they will continue to work with the administration to address those systemic issues,” Della Volpe said.

I’ve thought about George Floyd every day for the last 365 days. It will take a lot longer than that to make real progress.

But Matt Gorman, a Republican strategist, dismissed the idea that his party would be at an electoral disadvantage next year. “Hoping voters will vote against [Republicans because of] someone whose name is not on the ballot — Mitch McConnell — that’s just wishful thinking.”

Addressing policing practices might end up as a rare issue where bipartisan compromise is possible, Gorman added. “But I don’t think that’s the deciding issue for most voters in November 2022.”

Attending the private meeting at the White House was Floyd’s sister, nephew and brothers, as well as his former partner and their 7-year-old daughter, Gianna. Biden has often mentioned Gianna and her comment that “my daddy changed the world” by his death.

Psaki said the family’s “courage and grace” have “really stuck with the president,” and “he’s eager to listen to their perspective and hear what they have to say.”

Lindsay M. Chervinsky, a senior fellow at the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University, said that apart from policy changes, Biden has harnessed the power of his office to push a national dialogue around race. And unlike Obama, Biden may face fewer political land mines in doing so.

“Biden’s whiteness is actually something that makes that conversation possible in a more open way,” she said. “It’s safer coming from him.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.