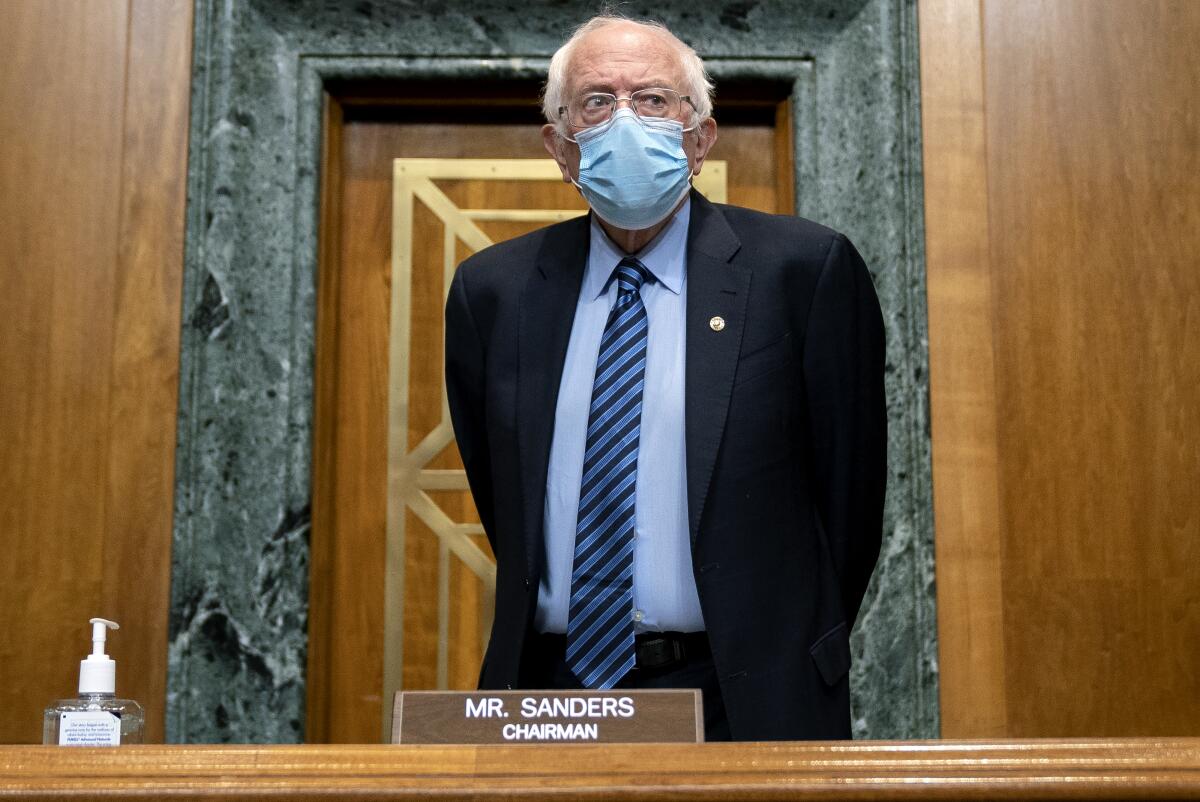

A new act for Bernie Sanders: Power broker

WASHINGTON — As control of the Senate teetered early this year, Republicans warned of a menace they feared would be unleashed on America if they lost power: Bernie Sanders would call the shots over the federal budget.

The reality for them may be even worse than they anticipated.

The longtime outsider, irritant of the Democratic and Republican establishments and cantankerous gadfly is proving shrewd at playing the inside game from his powerful new perch atop the Senate Budget Committee. His fingerprints are all over the historic $1.9-trillion relief package President Biden signed into law last week.

The democratic socialist who once encapsulated his time in Congress by writing a book titled “Outsider in the House” has now become the consummate insider in the Senate. The Bernie who honeymooned in the Soviet Union, who declared the Democratic Party hopeless, who sparked a revolt against an Obama administration tax deal during an 8 ½-hour filibuster, has transitioned into the Bernie orchestrating trillion-dollar deals.

“All of the committees played their role,” Sanders said in an interview just after the landmark relief bill won final congressional approval. “But all that stuff had to go through the Budget Committee. We had to put it together.”

“The result is we have a piece of legislation that will be more helpful to working families than any bill passed in Congress in decades,” he said.

Sliding back into the Senate after a second wildly popular — but ultimately unsuccessful — presidential run is tricky business, especially for a cranky maverick like the Vermonter, who was never fond of back-slapping, backroom plotting or wearing a suit.

But the 79-year-old who lost to President Biden in the 2020 primary is following a path carved out by earlier political celebrities such as Republican John McCain and Democrat Edward M. Kennedy, who bounced from defeat in their insurgent White House bids to final acts as legislative maestros.

“Being talked about as a presidential candidate is a huge distraction,” said Donald A. Ritchie, historian emeritus of the Senate. “You have to weigh everything you do with how it will affect running. It is a burden people are free from once they have run and lost and know it is not going to go that way.... If you were really a leader in the group running, you return with a lot more stature and can accomplish a lot.”

Sanders artfully navigated a high-stakes, high-wire act on the bill over the last several weeks, calming restive progressives who wanted more, fending off anxious moderates who wanted the price tag trimmed, and keeping the confidence of the Biden White House throughout.

His influence over the process was amplified by the tenuous majority Democrats hold over the Senate, which forced them to push the bill through the chamber using the Byzantine procedure known as reconciliation. Lawmakers use the tactic to advance spending measures with a simple majority vote, sidestepping threatened filibusters from opponents.

“It is a uniquely exasperating process,” said Senate Finance Committee Chair Ron Wyden, the Oregon Democrat who worked in tandem with Sanders to hold the line on the relief bill amid pressure to cut the $1.9-trillion price tag. “It very often feels like the premium is not on the best ideas but on trying to come up with some kind of workaround. Sen. Sanders showed you can work through this set of unique challenges and bring through the process a bill that really meets the moment and meets the times.”

He called Sanders a skilled practitioner of both the inside and the outside game, who played both to keep the COVID-19 relief package ambitious and to keep pressure on Biden and fellow Democrats to hold their ground.

The budget chair has extraordinary power in putting together packages advanced using the reconciliation tactic, but extraordinarily little room for error. The talents Sanders exhibited along the way often seemed at odds with his public persona as an uncompromising loner.

He worked the phones with gusto, advisors said, chatting almost daily with the White House chief of staff and Senate majority leader, but also with the chair of the 93-member Progressive Caucus in the House, Rep. Pramila Jayapal of Washington, who worked with him to keep the left on board.

None of it surprised Jayapal, one of many longtime Sanders colleagues who say his image as a gruff and rigid crusader belies his deep experience as a legislative tactician.

“Bernie was misunderstood,” she said. “People thought that he just yelled a lot, but didn’t get anything done. But I really don’t think that’s ever been true. And I also think that people underestimate the power of the movement, the power of populism, the power of people really believing in something — and Bernie never has underestimated that.”

Sanders expressed an emotion rarely associated with him as the package won final approval: joy.

“Our belief from Day One was that this bill had to be consequential,” he said. “The main point at this moment is the political shift in the Democratic Party. Democrats are now prepared to think big and not small.”

Nonetheless, all the triangulating, triage and smooth talking involved in the new role is taking Sanders out of his comfort zone.

“He would acknowledge his own shortcomings,” said Faiz Shakir, a Sanders advisor who managed the senator’s 2020 presidential campaign. “He’s said he doesn’t call people on their birthdays, he doesn’t like to chitchat, he doesn’t like the BS.… But he did a hell of a lot of it to get this passed.

“His role was to hold the line at $1.9 trillion,” Shakir said. “It was aggressive. It is a historic level of investment.... He held the line.”

One of the newest members of the Senate, California Democrat Alex Padilla, experienced the senator’s soft skills.

“Behind the scenes he smiles a lot more than you might think,” said Padilla, who sits on the budget panel with Sanders. “Of all the committees I sit on, his is the only committee that offers coffee and doughnuts in the back.”

But Sanders did more for Padilla than smiles and sugar. He recruited Padilla to speak on the floor with him as part of the push to keep a minimum-wage increase in the relief bill after the Senate parliamentarian ruled it could not be included in the reconciliation process. The sharing of that limelight impressed the California freshman and underscored the Vermonter’s aptitude for coalition building.

“This is a teachable moment for progressives,” said Jonathan Tasini, a consultant to politicians and groups on the left and author of “The Essential Bernie Sanders and His Vision for America.” “When you get power, what do you do with it? Do you simply use it for a rhetorical tool or see a somewhat more complicated calculation where I win something now and continue to build?”

Get our L.A. Times Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

It is a familiar conflict for Sanders. When he shocked the city of Burlington, Vt., in 1981 with his first big political victory, narrowly capturing the office of mayor, he nevertheless found a way to work with business leaders wary of a self-declared democratic socialist. They wanted to revitalize the waterfront. He wanted more low-income housing. A deal was struck.

Years later, when Sanders chaired the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee, he presided over a landmark bipartisan compromise that expanded access to care for veterans but also enabled them to see private doctors outside the government system.

The challenges he faces in his new role, though, are immeasurably more complicated as he tries to keep credibility both with the movement he built and with the Biden administration. Sanders was put in a tough spot when progressives demanded the parliamentarian be overruled — or even fired — after ruling that a minimum-wage hike could not be approved by the Senate through reconciliation, forcing Democrats to remove it from the COVID package.

Biden went a different direction, saying he would fight for the minimum wage another day. Sanders paused. He then worked with Wyden and others on a workaround that would have created tax penalties for employers who pay less than $15 per hour. It fell short in a floor vote, but put renewed pressure on the senators who balked, and on Biden. The fight isn’t over.

Sanders also exhibited his political maneuvering savvy when progressive activists pressured him to sink Biden’s nominee to run the Office of Management and Budget. The nominee, Neera Tanden, was a Democratic establishment favorite reviled by the left. Sanders asked Tanden pointed questions at a confirmation hearing, but signaled to the Biden administration that he would not be the one to scuttle the nomination. Other senators ultimately precipitated its collapse.

Sanders “has had to graduate from being the terrible-tempered intransigent progressive to somebody who has institutional responsibilities,” said Ross Baker, a political science professor at Rutgers University who studies the Senate.

Baker said that journey for Sanders is taking shape the same way it did for the late McCain, another outsider whose success in presidential politics was fueled by his distaste for conventional politics. “It is the same hard edge in both men,” Baker said. “But ultimately, they want to do deals.”

Yet some old habits die hard. Jayapal recalled Sanders calling her to express his gratitude that she had worked so hard for the progressive movement, and his regret for not telling her that enough. She told him it was very sweet. Sanders was emphatic that he is not sweet.

“I said, ‘Actually, I think you are,’” Jayapal said.

“Well, please don’t tell anybody,” Sanders told her. “It’ll ruin my reputation.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.