Column: How the pandemic is helping Biden advance his broader economic agenda

When Joe Biden launched his campaign for the presidency in 2019, his economic proposals were relatively modest updates of the middle-class-oriented agenda he championed as vice president under Barack Obama. “It doesn’t require some fundamental shift,” he said, pushing against the sweeping proposals of rivals like Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren.

Then came the pandemic.

Today, Biden’s economic message, retooled to address current needs, has real urgency.

“We can’t wait,” he said last week. “There’s a lot of people who are in real, real trouble — a lot of people going to bed at night, staring at the ceiling wondering … if they’re going to be evicted.”

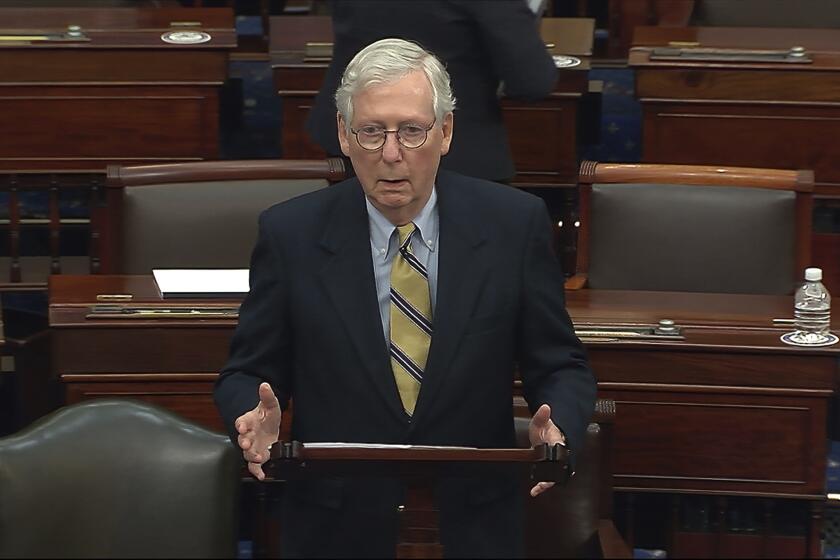

Former President Trump viciously castigated Sen. Mitch McConnell as a ‘dour, sullen and unsmiling political hack’ after he took to the Senate floor to denounce Trump’s behavior.

And Americans seem ready to spend to make things better. The huge $1.9-trillion pandemic relief bill Biden has proposed is wildly popular. A CBS News poll last week found that 79% of Americans want Congress to pass a bill as big as the one Biden proposed, including 61% of Republicans.

Biden isn’t stopping at pandemic relief. He’s also using the emergency to build support for the far broader program of economic reform he adopted midway through his campaign last year, including massive investments in manufacturing, technology, education and child care.

“We’re in a position to think big and move big,” he said.

He’s following the advice that Rahm Emanuel, then a member of Congress, offered during the financial crash of 2008: “You never want a serious crisis to go to waste.”

For Biden, that begins with the pandemic relief plan, a package that includes a $1,400 check for most adults, increased unemployment insurance, a child tax credit of up to $3,600 a year, $440 billion for state and local governments and $130 billion to help reopen schools.

And once that proposal is enacted, White House officials say, the president will turn to the broader, long-term economic proposals of his campaign, including a $400-billion “Buy American” plan to support manufacturing, $300 billion for research and development, more spending on clean energy and — if it doesn’t pass as part of the pandemic package — a $15 minimum wage.

It’s an ambitious agenda: a dramatic expansion of federal government spending to create jobs, especially in manufacturing and strategic technologies.

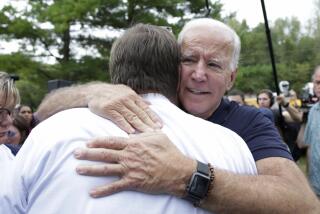

Biden’s economic populism is aimed, in part, at the same voters Donald Trump appealed to when he called for revitalizing American manufacturing and bringing jobs back home — but only in the sense that Biden, too, has promised to repair some of the damage wrought by the long decline in manufacturing jobs.

“A lot of white working-class voters thought we forgot them,” he said last year during a campaign tour of faded industrial towns in Pennsylvania. “I get them. I get their sense of being left behind.”

He’s kept a few of Trump’s policies, most notably the tough stance on trade with China. But the difference in the two populisms is illustrated by the predecessor each president chose as a model.

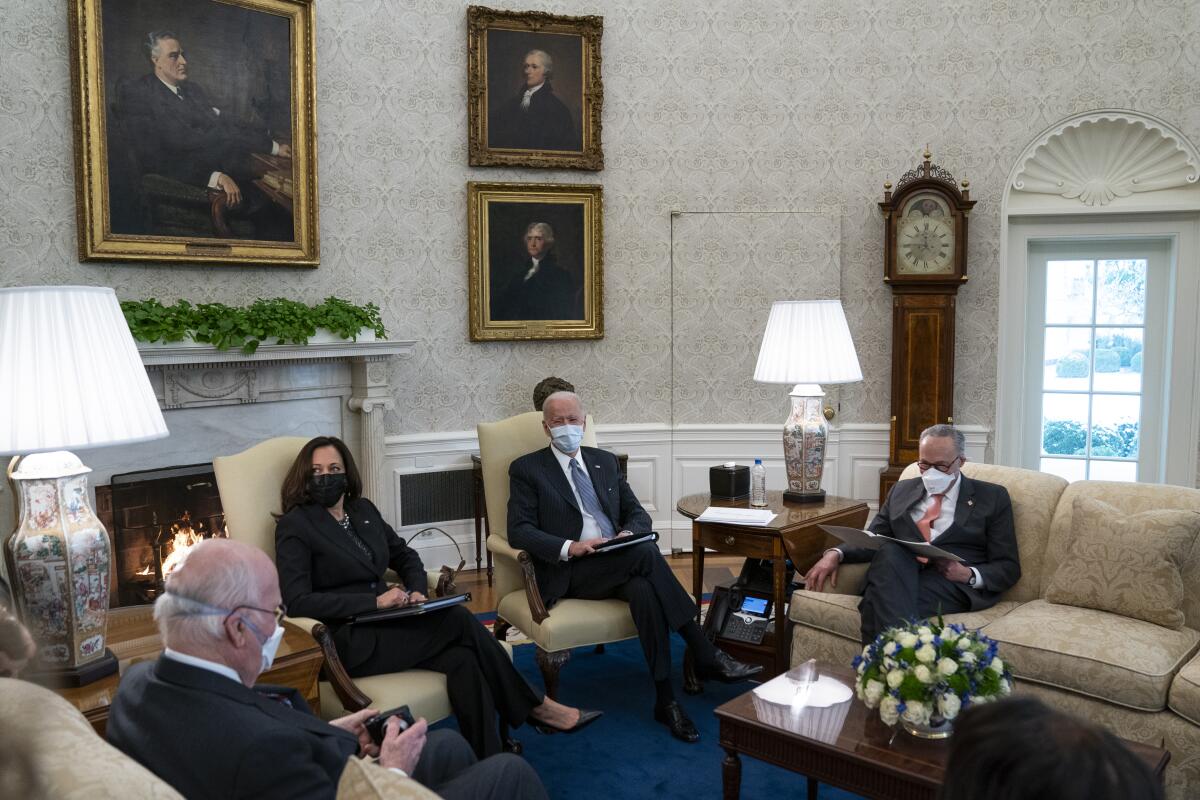

In Trump’s Oval Office, he hung a portrait of Andrew Jackson, the 19th century nationalist who warred with bankers on behalf of working-class white Americans but also supported slavery and pushed tens of thousands of Native Americans off their ancestral lands.

Biden replaced Jackson’s portrait with one of Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Depression-era Democrat who enacted Social Security, vastly expanded the federal government and was reelected three times.

If Biden’s economic agenda were being proposed by full-throated progressives like Sanders or Warren, it might sound extreme to many voters. But his long record as a relatively centrist Democrat could insulate him from that hazard, much as FDR’s aristocratic background allowed him to tack left.

“Voters view him not as a radical, but as a get-things-done moderate,” Biden’s campaign pollster, John Anzalone, told me. “Voters are incredibly transactional right now. They want help and they want it quick.”

Republican opposition to both parts of Biden’s agenda — the short-term relief plan and the longer-term reforms — has been muted so far, mostly because GOP leaders have been too busy with family quarrels over Trump’s legacy to offer much of an alternative to the president’s plans.

That’s unlikely to last. There will be plenty for conservatives to oppose soon enough, beginning with the $15 minimum wage and those new big-government economic programs — not to mention the increase in corporate taxes Biden has proposed to help finance it all.

But as the president nears the end of his first month in office, it’s possible to imagine that by the end of 2021 he could be claiming credit for a rebounding economy and pressing ahead with his broader proposals. If he succeeds, the Biden presidency could be transformative in a way even his supporters didn’t expect.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.