Lawmakers question Biden’s Pentagon nominee on civilian control of the military

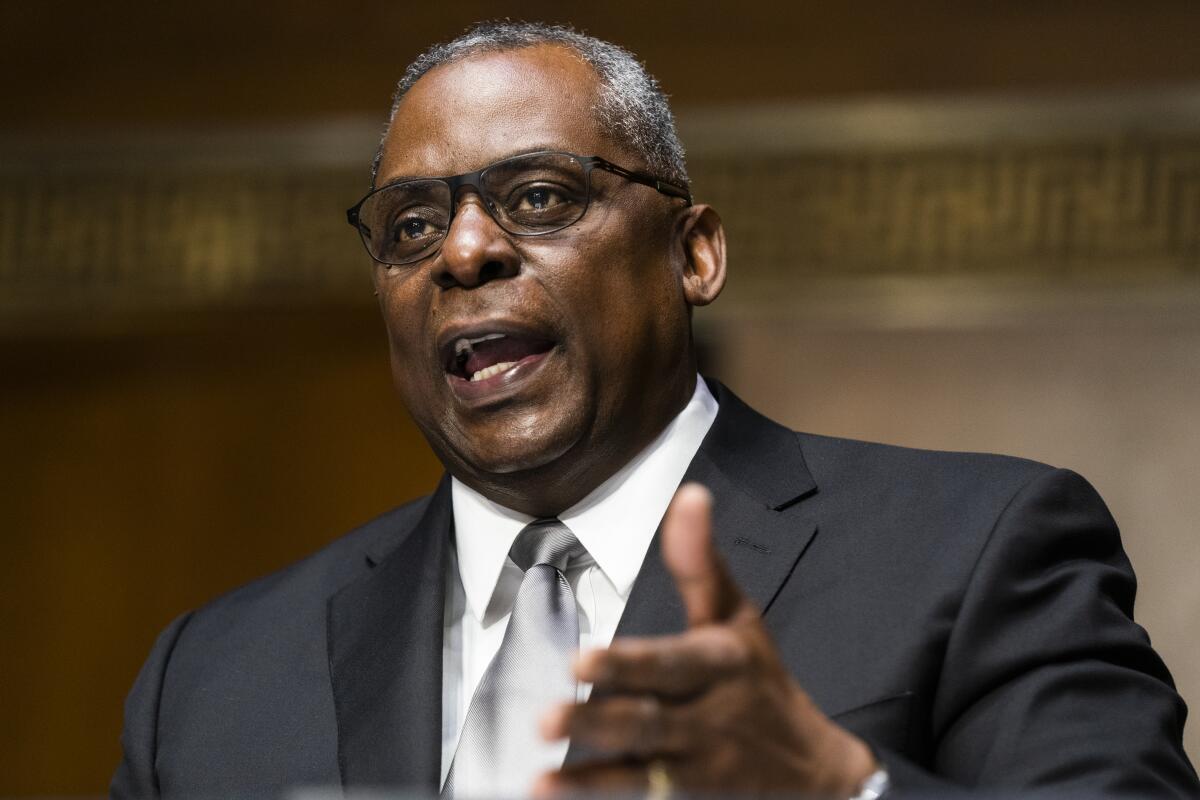

WASHINGTON — President-elect Joe Biden’s nominee to run the Pentagon, retired four-star Army Gen. Lloyd J. Austin, reassured lawmakers Tuesday that he endorses civilian control of the military and could effectively oversee the armed forces despite his decades in uniform.

“I would not be here, asking for your support, if I felt that I was unable or unwilling to question people with whom I once served and operations I once led, or too afraid to speak my mind to you or to the president,” Austin told the Senate Armed Services Committee at his confirmation hearing.

Austin’s nomination, only four years after another recently retired general, James N. Mattis, was confirmed to run the Pentagon, has run into resistance from some lawmakers wary of granting another exception to the principle that the U.S. military should be under civilian oversight. Before Austin can be confirmed, the House and Senate must vote to waive a law that requires nominees for Defense secretary to have been out of the military for more than seven years. Austin retired nearly five years ago.

Installing his national security team quickly is a priority for Biden, not only because he wants to reverse or modify some Trump administration policies but because of diplomatic, military and intelligence problems he will face early in his term.

If confirmed, Austin — a 1975 West Point graduate who rose to command U.S. forces in the Middle East — will be the first Black secretary of Defense.

Though lawmakers from both parties have voiced varying levels of opposition to granting a waiver, a senior Biden transition official said Congress likely will approve one, and Austin would comfortably win Senate confirmation.

“I’ve never been all that concerned about the seven years, but others have,” said committee Chairman James M. Inhofe, a Republican from Oklahoma who oversaw the hearing but will be giving up the leadership post when the Democrats assume control of the Senate, probably Wednesday.

Sen. Jack Reed (D-R.I.), who is taking over as chairman, had voiced misgivings about granting another waiver at the time Mattis’ was approved. He said Tuesday that Austin could “mitigate” the concerns, “if you demonstrate your commitment to empowering civilians” at the Pentagon.

At least two Democrats on the committee have announced their opposition to granting Austin a waiver: Sen. Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut and Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts. Some may vote against the waiver and then vote for Austin’s confirmation. Republican Sen. Tom Cotton of Arkansas has also said he opposes waiving the law, as have several House members.

Before Mattis’ waiver, only one had ever been approved — for retired Gen. George C. Marshall, who served one year as Pentagon chief 70 years ago.

Austin appeared in person at the hearing, while most lawmakers appeared by video. He acknowledged that being one of the top civilian members of Biden’s national security team would require shifting his perspective but vowed to rely on civilian appointees in the Defense Department and to work with Congress.

Among other issues, as secretary Austin would face debates about whether to continue President Trump’s policies of moving toward withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria and whether to rejoin the Iran nuclear agreement that Trump rejected. He would also likely be tasked with helping to restore allies’ faith in U.S. defense commitments, which has frayed considerably under Trump.

Referring to his decades in the Army, including his time in command in Iraq and as overall commander of U.S. forces in the Middle East, Austin said, “In war and in peace, I implemented the policies of civilians elected and appointed over me.”

But, he added, “I know that being a member of the president’s Cabinet — a political appointee — requires a different perspective and unique duties from a career in uniform.”

Austin vowed to purge the military’s ranks of “racists and extremists” and to address sexual harassment, a rampant problem in the armed forces. Echoing Biden, he said the most immediate challenge facing the country is the COVID-19 pandemic.

Biden, as vice president in the Obama administration, worked closely with Austin during the troop drawdown in Iraq in 2010 and 2011, when Austin was in Baghdad as the top commander of U.S. forces. Austin recommended that President Obama keep as many as 24,000 troops in Iraq, but the White House, including Biden, opposed the plan.

The two worked closely when Austin was in charge at Central Command and U.S. troops went back into Iraq in 2015 after the Islamic State took over large parts of the country. Biden came to admire Austin’s publicity-averse style and willingness to carry out White House decisions loyally, even if he disagreed with them, associates said.

Austin also worked with Biden’s late son, Beau, who served on the general’s staff in Iraq; they attended Mass together and stayed in touch following their deployments — another important bond with the president-elect.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.