Biden lavishes time and money on key industrial states, but hasn’t locked them down yet

WASHINGTON — The worst strategic mistake Hillary Clinton made in her 2016 campaign for president, many analysts believe, was overconfidence about three states Democrats had won in every presidential election since 1992 — Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.

No one is going to accuse Joe Biden of taking those states for granted.

The Democrats’ presidential nominee is showering money, staff and time over those states — the “blue wall” that crumbled when Donald Trump’s victories by tiny margins in all three propelled him to the White House.

By this weekend, Biden will have made five trips to those battleground states in less than two weeks.

He traipsed across Pennsylvania as he began venturing from quarantine in his Delaware home last month. On Friday, both he and Trump are scheduled to be in the state to commemorate the victims of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks.

Biden’s first trip further afield was to Wisconsin. He’s deployed hundreds of campaign staff and spent millions on advertising.

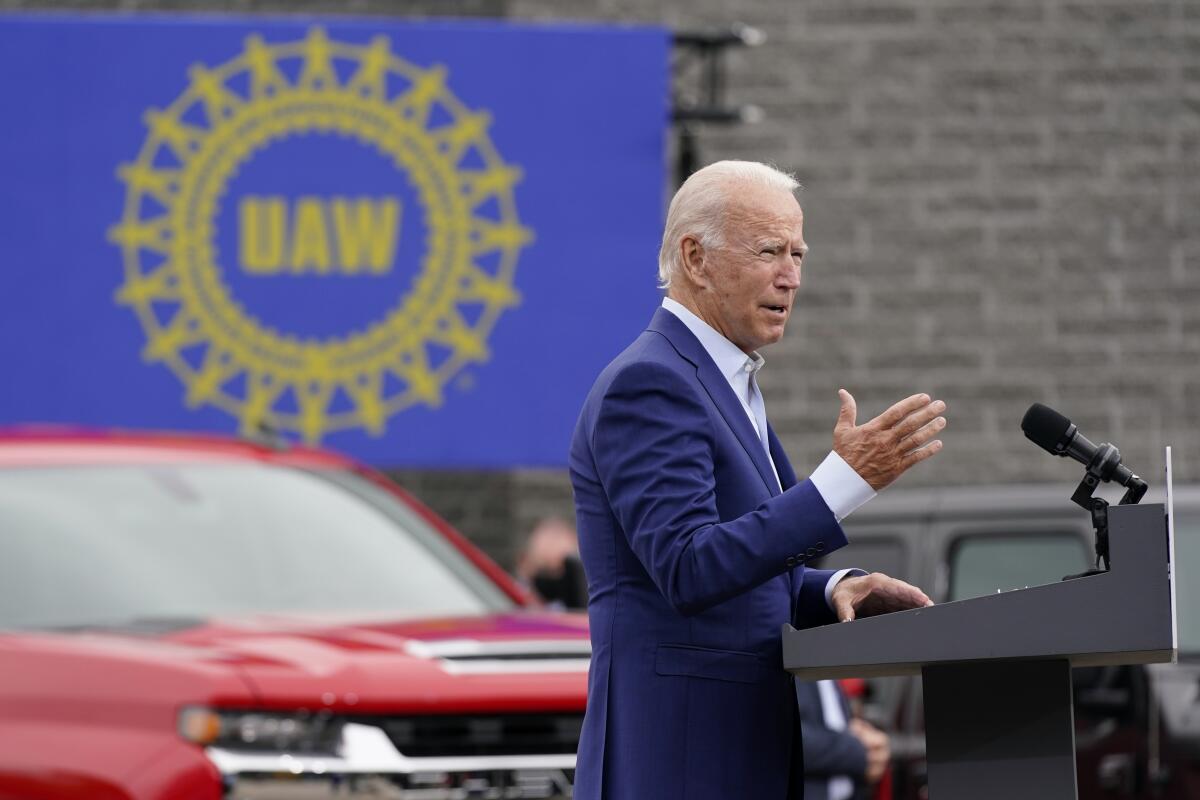

On Wednesday, he went to Michigan to unveil a new economic policy to discourage the outsourcing of jobs — a scourge of the manufacturing sector across the industrial belt.

“Make it in Michigan, make it in America,” Biden said in Macomb County near Detroit — home to many of the white working-class voters he aims to bring back into the Democratic fold.

For all that, Biden has yet to lock down those crucial states. He has held a consistent polling lead over Trump in each of them, but not enough to feel confident.

Trump and Biden have been shadowing each other in campaign appearances across the region. In addition to Friday’s Pennsylvania trips, both went to Wisconsin last week, two days apart. Both are in Michigan this week, one day apart.

After Trump bypassed Jacob Blake’s family and praised police, Biden met with slain man’s family and called for the officers involved in the shooting to be charged.

“You can’t take any of these Midwestern states for granted,” said Rep. Debbie Dingell (D-Mich.), who in 2016 pleaded for Clinton to do more to communicate with white working-class voters in her state.

Clinton famously made no campaign stops in Wisconsin, which critics blamed for a drop in Democratic turnout. She put plenty of resources into Pennsylvania — including a star-studded election-eve rally in Philadelphia — but it was not enough to overcome the surge of rural blue-collar voters turning out for Trump.

The result was a shocking triumph for Trump in three states that few Democrats believed were in question. In an election in which more than 130 million people voted, Trump won those three states by fewer than 80,000 votes.

Job one for Biden has been to win them back.

His claim to have special appeal in the region — as a Scranton, Pa., son of a working-class family — was a big part of his case against his Democratic primary rivals.

Some Democrats have downplayed the importance of the region, arguing that the party’s best path to victory runs through diverse Sun Belt states that could be flipped from the GOP rather than recovering lost ground among the white working class in the Midwest.

Biden’s campaign has tried to do both, making some efforts to compete in states like Florida, Arizona and Georgia that Trump won in 2016. Biden plans to make his first trip to Florida next week. But campaign investments in those states pale compared with what he has poured into rebuilding the blue wall.

The campaign has fielded 242 staffers in Wisconsin and 347 in Pennsylvania — compared with 112 in Georgia.

In September so far, the Biden campaign had more ad airings in each of the three blue-wall states than any state but Florida, according to data compiled by Advertising Analytics. Taken together, Biden’s campaign had four times as many ad airings in Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania as the Trump campaign.

Polling averages put Biden ahead of Trump by mid-single digits in all three states. That is close enough to spook Democrats, who remember Clinton leading polls by similar margins.

“It’s close, and it is tightening,” said Michelle Deatrick, a Democratic National Committee member from Michigan. “We need to work very hard in Michigan. The fact that the Biden campaign is coming shows that they are very aware of it.”

One advantage Biden has over Clinton is a spike in voter interest in the election.

“The dynamics are completely different between 2016 and 2020 in terms of motivation to vote,” said Richard Czuba, a nonpartisan pollster whose survey for the Detroit News this week showed Biden with a 5-percentage-point edge in Michigan.

“It’s the single highest level of motivation in Michigan I’ve seen in 37 years of polling.”

In Michigan, Biden is banking on goodwill generated by his role, as Barack Obama’s vice president, in overseeing an auto industry bailout and other economic relief in 2009. The state’s former governor, Republican Rick Snyder, has endorsed Biden.

Trump’s remaining strength in the region: many voters prefer him to Biden for handling the economy. Biden worked to close that gap in his Michigan speech Wednesday by arguing that Trump had failed to make good on promises to protect American jobs and keep manufacturing from moving overseas.

“President Trump has broken just about every promise he’s ever made to the American worker,” Biden said. “He’s failed. He’s failed our economy and our country.”

Joe Biden unveils his economic recovery plan in a speech in Pennsylvania and accuses President Trump of being out of touch.

The Trump campaign has been buoyed this week by new internal polls showing Biden’s lead in Michigan, which appeared insurmountable through much of the summer, narrowing in recent surveys, one official said.

But amid an effort to curtail spending under new campaign manager Bill Stepien and a still unsettled swing-state strategy, it’s unclear how hard Trump will fight to keep Michigan in his column this fall. The campaign may intensify focus on states like Wisconsin or even Minnesota, if they seem more likely to remain or become red.

In Pennsylvania, Biden faces a fight despite many assets. He was born there, located his national headquarters in Philadelphia, kicked off his campaign in Pittsburgh, and held more events in the state than any other since COVID-19 hit, due to its proximity to his home in Delaware.

Former Vice President Joe Biden, jumping into the 2020 presidential race as the apparent front-runner, flashed his political calling card Monday with a kickoff rally at a Pennsylvania union hall that underscored his claim to be the candidate best equipped to win over blue-collar workers in crucial states that gave Donald Trump his victory in 2016.

When he traveled to Pittsburgh last week, in a speech about racial justice, protests and urban violence, Biden dropped in a shout-out to a core local economic concern: He declared that he was not calling for an end to all fracking, as Trump ads in the area have contended. Stopping short of the full ban many progressives want, Biden has said he wants to block new federal permits for drilling on public land.

Biden’s clarification was welcomed by those like Rich Fitzgerald, Allegheny County executive, who thought support for a fracking ban would crush his chances in western Pennsylvania.

“There’s no way we could have been able to sell those policies and candidates who back those policies in western Pennsylvania,” said Fitzgerald, who met with Biden after the speech and thanked him for refuting the Trump ads on the topic. “He may have to say it again in debates,” he added.

In Wisconsin, the outlook remains clouded. Republicans had thought the unrest in Kenosha, in the aftermath of the police shooting of Jacob Blake, would create a promising environment for winning over swing voters with Trump’s hard turn to a “law and order” message.

That seems not to have happened. A new Wisconsin poll from Marquette University Law School found the presidential contest essentially unchanged.

Wisconsin voters’ support for racial justice protests and the Black Lives Matter movement has dropped in recent months, but that did not translate into changed views of the presidential contest. It may, however, have helped consolidate GOP support for Trump. The poll found that Republicans’ approval of how Trump has been handling recent protests rose to 87%, up from 65% in August.

Democrats had hoped for a boost in Wisconsin from their convention, originally scheduled to be held in Milwaukee. But the pandemic forced the cancellation of the in-person convention in favor of an online affair. The Marquette poll found that neither party’s convention produced any significant shift.

“Despite all those real world events, there’s very little change in this poll,” said Charles Franklin, director of the poll.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.