Before the coronavirus, Joe Biden offered stability. Now he’s talking bold change

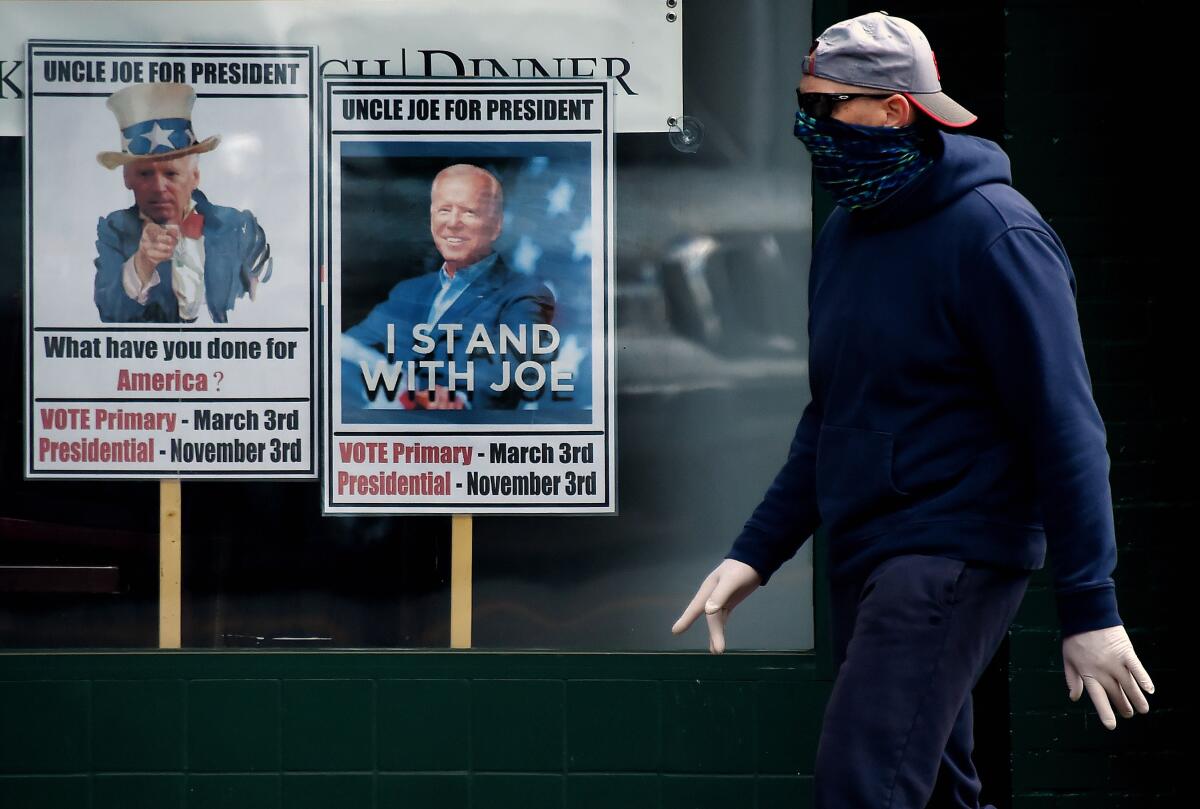

With the world turned upside down by the novel coronavirus, Joe Biden has refashioned his presidential campaign to shift from an emphasis on steadiness and stability to the promise of big, bold change.

While the fundamentals of Biden’s White House bid remain the same — with a call for such Democratic standbys as expanded healthcare and greater equality — he talks less about restoring things as they were before President Trump’s disruptive time in office and more about where the country heads from this unsettling place.

The more transformative vision is a response to the greatest economic and health crises most Americans have ever faced and the way the toll of COVID-19 has changed public attitudes and opened the door to new political possibilities.

“You don’t have a once-in-a-century pandemic wreaking both the human devastation and economic devastation that COVID-19 has wrought without producing new thinking about what’s required — not just bringing this country back but, as the VP likes to say, build back better,” said Jake Sullivan, a senior campaign advisor.

In the coming weeks, Biden said, he will lay out his plan for the “right kind of economic recovery,” which campaign aides say will include boosting the so-called “caring economy” of child care, nursing and healthcare aides; pouring major investments into public health infrastructure; expanding the domestic production of critical medical and protective equipment; and ushering in a new era of corporate responsibility for the private sector, which, Biden pointedly notes, has been bailed out twice in 12 years.

Disruptive events like the COVID-19 outbreak can end political inertia and result in bold changes

The forcefully populist messaging could help Biden in two ways: sharpening the contrast with Trump, who still holds an edge with voters on economic issues, and attracting those progressives who may still be smarting over his defeat of Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren in the Democratic nominating contest.

Biden’s approach in the primaries — offering himself as a keeper of the liberal faith but one more pragmatic and electable than Sanders or Warren — was a winning strategy in the time before the pandemic. Now, he echoes some of their grander rhetorical flourishes, pledging to “transform the country” and “change the system.”

There are signs that the toll of the coronavirus crisis — with nearly 90,000 Americans dead so far and roughly 36 million unemployed — has so rattled the electorate that broad segments may be open to a more expansive government.

A recent poll from Navigator Research, a progressive group that does daily coronavirus-related surveys, found that 50% of Americans said the federal government should be doing more to improve the economy. A late April poll by the liberal Groundwork Collaborative found roughly 70% of respondents backed “major, sweeping action” by the government to address the pandemic’s economic impact.

Obama’s choice of a vice president altered the course of Joe Biden’s career. It also is shaping how Biden is going about choosing his own running mate.

The nonpartisan Pew Research Poll has similarly found high support for government coronavirus aid across party lines, a notable contrast from the polarized views of the 2009 stimulus package adopted amid the Great Recession.

There is a risk, however, that Biden could overreach in a time when voters may crave a reassuringly even-keeled approach more than massive changes.

“I’d be a little careful,” said Paul Begala, a veteran Democratic strategist who helped put Bill Clinton in the White House. “I think voters are a little skeptical of grandiose plans to remake everything. His party rejected the revolution and chose reconciliation. I think that’s why Joe beat Bernie.”

It’s not so much about the fundamental principles of what he’s proposing being different... It’s about scaling up to meet this moment.”

— Kate Bedingfield, Biden’s deputy campaign manager

Advisors to the former vice president said Biden first began thinking of how the virus would require a more sweeping policy approach in March, soon after stay-at-home orders went into effect across the country.

By early April, he was telegraphing the scope of his expanded thinking, musing in a CNN interview that the economic ruin could equal or eclipse what President Franklin D. Roosevelt faced in navigating the Great Depression. In an interview last month with Politico, he called for a new stimulus bill that was “a hell of a lot bigger” than the $2-trillion package passed by Congress.

Campaign aides are quick to say that Biden’s statements mark an evolution, not a revolution, in his thinking. From the start of the campaign, Biden’s platform, which included calls for a $15-an-hour minimum wage and $1.7-trillion plan to combat climate change, was more progressive than any Democratic nominee before him.

“It’s not so much about the fundamental principles of what he’s proposing being different. Or looking at this crisis and saying, ‘We have to throw out the policy playbook I’ve been working from and start a new one,’” said Kate Bedingfield, Biden’s deputy campaign manager. “It’s about scaling up to meet this moment.”

In response to the coronavirus, Biden has so far called for canceling at least $10,000 of student loan debt per person during the crisis and increasing Social Security payments by $200 per month — notions that were originally promoted by Massachusetts Sen. Warren.

Those initiatives came on the heels of his steps immediately after locking up the nomination to adopt Warren’s bankruptcy reform proposal. He also proposed lowering the Medicare eligibility age to 60 and offering tuition-free public college for many students, steps in the direction of Vermont Sen. Sanders’ signature policies.

Toss-up contests from Arizona to Florida hold the key for President Trump and Joe Biden.

The steady embrace of his rivals’ policies is a sign that Biden is offering more than just a “hat tip” to the left, said Adam Green, co-founder of the Progressive Change Campaign Committee.

“The good news is that so many progressive solutions where there’s a lot of enthusiasm among voters happen to be the solutions that meet the moment with this coronavirus crisis,” Green said, “so it creates a win-win for Biden to both be the president people want and unify the party by bringing progressives over.”

Still, some on the left say they’ll need to see more. Ben Tulchin, a top advisor in Sanders’ two presidential campaigns, said Biden’s hints of a New Deal-style presidency are “encouraging” but incomplete.

“He’s just got to follow through ... on big and bold policies, which he hasn’t done yet,” Tulchin said. “It will require retooling what he did in the primary, because in the primary it was about pushing back on Bernie’s big, bold policy proposals.”

Biden formalized those overtures to the left last week when he announced “unity” policy task forces that consist of Biden and Sanders allies, including some of the latter’s most vocal backers, such as Democratic Reps. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York and Pramila Jayapal of Washington state.

The Republican National Committee quickly seized on the alliance, painting Biden as a Sanders-esque revolutionary.

“Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders are two sides of the same socialist coin,” said Steve Guest, a party spokesman. “Now with his full embrace of AOC’s radicalism, Biden is the bannerman for the socialist agenda.”

Biden’s campaign, meanwhile, has stepped up its attacks on Trump’s handling of the pandemic’s economic fallout, charging that the administration’s efforts to aid businesses have favored the well-off and well-connected over small business owners. Biden and Warren co-wrote an op-ed blasting Trump for shrugging off oversight requirements for coronavirus aid.

“Obviously, this new crisis gives [Biden] and his campaign an opportunity to reassess and reevaluate, and he can say that in earnestness,” Tulchin said. “He doesn’t have to apologize for shifting gears because the world has changed.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.