Coronavirus could deliver blow to struggling rural hospitals

WASHINGTON — Rural hospitals nationwide are bracing for a wave of high-risk coronavirus patients that could break an already fragile healthcare system, one facing shortages of supplies and a scarcity of doctors so dire that some centers might have to shut down if a single physician contracts the disease.

“There is literally no room for error here,” said Alan Morgan, chief executive officer of the National Rural Health Assn., which represents 21,000 healthcare providers and hospitals. “Rural America is a tinderbox of a healthcare crisis for those most in need.”

About 2,000 hospitals serve more than 60 million people in rural areas, about a fifth of the U.S. population, and experts say they are simply not equipped to handle a pandemic that has claimed more than 7,000 lives and infected more than 275,000 people in the U.S. as it spread from China and around the globe. Dense urban areas have been the hardest-hit so far — New York City has recorded about 1,500 deaths, making it the epicenter of the outbreak in the U.S. But it’s expected to be only a matter of time before the virus strikes rural America.

Doctors at rural hospitals say they are getting ready, if belatedly, and bracing for the impact.

Dr. Gregory Byrd, vice president of medical affairs for the 25-bed Shenandoah Memorial Hospital in Woodstock, Va., said his staff is improvising on the fly. It has started using video and telephone conferences to reach patients before they get to the hospital, prescribe them medications or refer them to offices dedicated to the coronavirus. Those who show up at the hospital must first enter a tent erected outside the emergency room, he said.

Patients deemed likely to have the illness are sent to a “hot zone” at the hospital. The rest are treated in another area. In recent weeks, the hospital has transferred several patients sick with the virus to a sophisticated medical center in Winchester, Va., about 45 minutes away.

“This has been the craziest two weeks of my career,” Byrd said. “We are trying to plan for something we had theoretical knowledge would happen one day, but we just weren’t prepared. We were all caught with our pants down.”

The coronavirus could inflict disproportionate damage on the American countryside for a variety of reasons. Its population is generally older, heavier and has more underlying health conditions than city and suburban dwellers. Such patients are more likely to need risky invasive care.

Yet its healthcare system is ill-prepared for the need. It has been hard-hit by social and economic forces, operating mostly in areas that have lost population and serving a disproportionate number of patients whose age and condition make them among the most expensive to treat. Rural hospitals rely on government payments, but many are in Republican-led states that have resisted expanding Medicaid to more low-income adults and children. Nearly half of rural hospitals lost money last year. In the last decade, more than 100 rural hospitals have closed, eight of them since January.

Instead of gearing up as the coronavirus spreads to rural areas of the Pacific Northwest, outlying hospitals face critical cash shortages that could force some to go out of business.

The pandemic is likely to exacerbate those trends. To keep hospitals afloat, administrators have focused intensely on the bottom line, boosting outpatient and elective procedures and cutting back on costs like stockpiles of protective gear. Yet the virus has forced hospitals to halt most elective surgeries, both to preserve stores of masks, gloves and scrubs and to reduce chances of spreading infection, thus eliminating a major source of revenue.

Rural hospitals will face trouble boosting those stockpiles. They don’t have the political sway or buying power to obtain such supplies in a chaotic open market dominated by larger hospitals and their networks.

Also, they were not built to treat people with contagious pathogens. Many don’t have the space for makeshift infectious disease wards. And while major medical centers have specialists directing patient care, rural hospitals rely on generalists who may not have access to the most up-to-date treatments.

They have evolved in recent decades from full-service medical centers into army-like “field hospitals” that often triage and stabilize patients before sending them to more sophisticated facilities. While that system is adequate for car-crash victims and those with minor illnesses and injuries, it is not equipped for a wave of coronavirus patients.

But if larger regional centers become overwhelmed, rural hospitals will have no place to send their sickest patients. Most rural hospitals have only one or two ventilators, administrators say, and their doctors and nurses have little experience keeping people alive on such devices for days on end, a routine outcome for critically ill coronavirus patients.

“Managing patients over time will be a big problem,” said Dr. David Wallace, an assistant professor of critical care medicine at the University of Pittsburgh. “Rural areas are just not set up with the same infrastructure to handle a large surge of patients.”

In the absence of a nationwide distribution plan, many smaller hospitals, nursing homes and physicians who need medical equipment are being left behind.

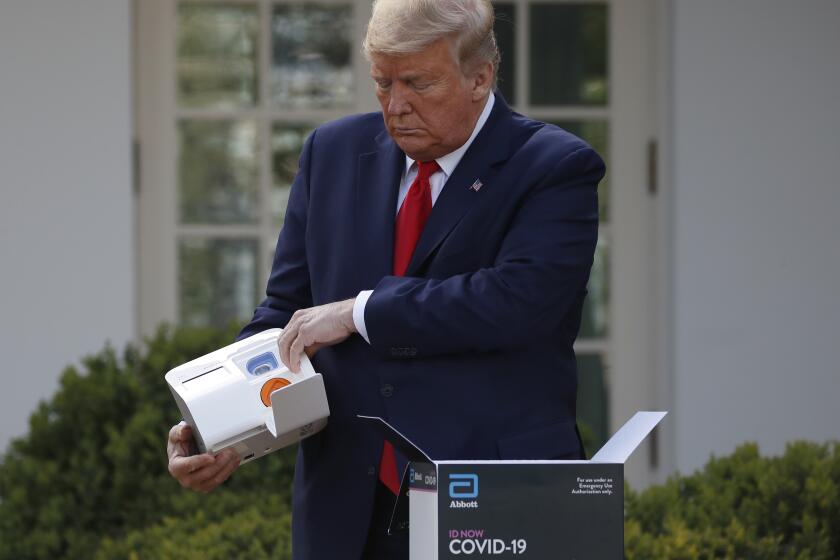

Politics also could be at play. As President Trump often notes, rural America backed him by a wide margin, and it remains loyal. Hospital administrators said they were concerned that residents in their regions had not taken the threat as seriously as they should have because, until recently, Trump and his allies at right-wing media outlets for months downplayed it. Trump supporters distrust the mainstream media and many believed news outlets over-hyped the virus’ dangers, they said.

Rural areas “won’t be spared. In fact, we could get walloped because of where we get our news, and the perception that urban problems are not necessarily rural problems,” said an executive of a state hospital association, who requested anonymity. “There is no doubt the president’s early skepticism is playing a role in this. And then his people were skeptical about it.”

But now, the executive added, “the president seems to be taking it more seriously, and rural America will likely follow his lead.”

Administrators of rural hospitals say they have so far seen only a trickle of coronavirus patients. Those without COVID-19 symptoms or with minor illness are being sent home to rest, and patients in need of more acute care are being diverted to regional centers.

Teresa Grimes, chief executive officer of the Washington County Hospital & Nursing Home in Chatom, Ala., said her facility was taking steps to reduce the chances for transmission and to better treat those with the disease. It has enhanced its screening of employees, visitors and patients, and is beefing up disinfection of high-touch areas. A resident physician, who recently spent time in a critical care ward of another hospital, has been training nurses and doctors on how to best use the hospital’s two ventilators, Grimes said.

“We are as prepared as we can be,” Grimes said. “Two weeks ago, I got a call from a hospital in north Alabama that needed ventilators. I told them if nobody else could help them to call me back and I would see what I could do. But I only have two, and there may come a time when we need them here.”

One thing that might work in rural America’s favor, doctors said, is that the virus may not spread as quickly or deeply in sparsely populated areas as it does in densely populated places like New York City, Detroit or New Orleans.

Said Lorenzo Serrano, chief executive officer of a 19-bed Winkler County Memorial Hospital in west Texas: “It is easier to social distance in rural America.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.