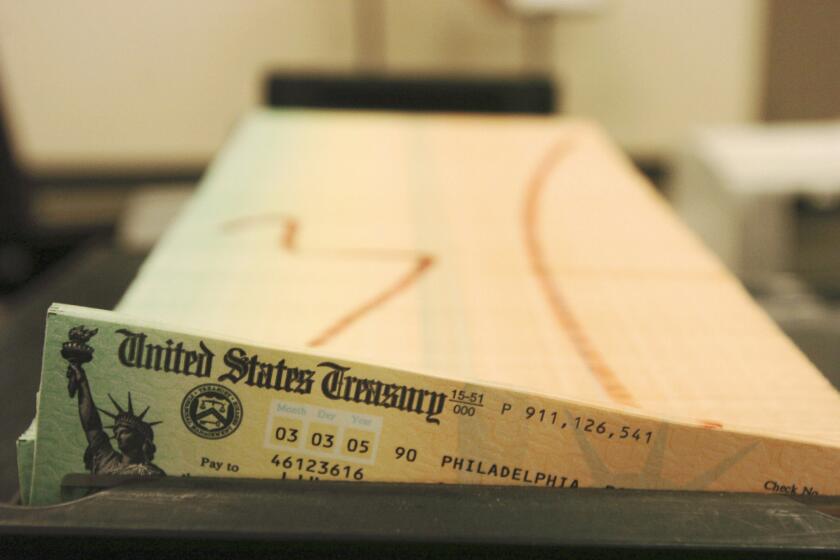

Mass layoffs hit the economy. Can the government’s $2-trillion stimulus plan stem the tide?

WASHINGTON — Even in the darkest hours of 2008, when the nation teetered on the edge of a second Great Depression, Congress never passed anything close to the economic stimulus plan scheduled for final approval Friday.

The Senate’s roughly$2-trillion response to the devastating economic effects of the coronavirus stands out not only for its record amount — almost 10% of U.S. gross domestic product — but in giving employers unprecedented — and untested — financial incentives to keep people on their payrolls.

For the record:

7:37 a.m. March 31, 2020An earlier version of this story said the roughly $2-trillion coronavirus relief package would provide an additional $600 a week for recipients of unemployment insurance benefits through the end of the year. The program provides for additional payments for up to four months.

In addition to providing direct help to those who are losing their jobs and livelihoods due to a pandemic, the bill includes novel ideas designed to encourage employers to avoid layoffs, including offering loans that could turn into grants if companies maintain enough workers, payroll mandates for large firms and expanded government help for state unemployment insurance programs.

“We’ve never in all the stimulus since World War II had direct payments to employers to retain people on their payrolls,” said Michael Bernick, former director of California’s Employment Development Department and now an employment attorney at Duane Morris in San Francisco. “This is the most aggressive employee retention effort we’ve seen — well beyond the previous efforts from the Carter administration in the 1970s through the more recent Great Recession.”

The Senate package will doubtless ease some of the immediate economic pain, but it remains to be seen whether it will be enough to send millions of suddenly unemployed workers back to their jobs and prevent more massive layoffs in the days ahead.

And there are already discussions among lawmakers for the need for another relief and stimulus package, given the sheer magnitude of economic impact and the uncertainty over how long the health crisis will last. Experts say the Senate plan is meant to cushion the blow and tide things over for a few months at most.

Since the shutdown of large sectors of the American economy earlier this month, countless restaurants, hotels, entertainment venues and manufacturers already have laid off millions of workers or ratcheted back their employees’ hours.

When will stimulus checks go out? Who qualifies for a check? And other frequently asked questions.

The Labor Department said Thursday that in just the seven-day period ending March 21, about 3.3million people filed for first-time unemployment claims.

That seasonally adjusted number was five times greater than any single week since record-keeping began in 1967 — and it points to what many expect will be a dramatic increase in the jobless rate, possibly even into double digits later this spring.

In California, more than a million people have applied for unemployment benefits this month, Gov. Gavin Newsom said Wednesday.

It’s clear that Washington policymakers believe they won’t be able to prevent a lot of COVID-19-related layoffs and large-scale unemployment, which for some workers will be permanent.

With that in mind, the Senate relief package includes a vast expansion of unemployment benefits to the tune of $260billion. Currently, the amount of jobless benefits varies from state to state, but they typically don’t replace more than about half of an employee’s wages, and then only for up to 26 weeks. In California, the maximum weekly payment is $450.

The stimulus package would add $600 a week to that cap for up to four months and would extend the maximum length of benefits by 13 weeks.

Significantly, the Senate’s expansion of the unemployment insurance program would enable states to offer jobless compensation to workers who are not laid off, but have their hours — and thus their incomes — cut back. In some states, such workers are not currently eligible to claim unemployment.

Harry Holzer, a public policy professor at Georgetown University, said 26 states, including California, have such so-called work-sharing programs, which spread the pain during downturns by reducing hours for everyone to avoid or minimize layoffs.

Work-sharing benefits are common in Western Europe but relatively new in the United States. The Senate plan also provides subsidies for states that don’t have such programs to develop them.

“I’m hoping that this will also help firms, especially those that don’t want to take out big loans, to convince them” to retain employees and cut back hours instead, Holzer said.

For smaller businesses, which employ the bulk of American workers, the Senate package offers a significant incentive for them to hold onto employees: loan forgiveness.

The legislation earmarks $366billion for low-interest loans up to $10million for a coronavirus-affected business with fewer than 500 employees. And the more a borrower maintains its staffing level in the short term, the larger the amount of loan forgiveness.

Loan funds spent for rent, utilities and other business operations also could be subtracted from the amount of money to be repaid, but the biggest deduction in the loan would be tied to employment levels.

“So small businesses can get liquidity now. But if they hold onto their workers, they ultimately won’t have to pay most of that money back,” said Marc Goldwein, senior policy director for the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

“There’s an incentive to keep your workers because, in some ways, it’s free to pay them,” he added. “The federal government is kind of picking up the tab.... It’s a big deal.”

Meagan E. Garland, a Duane Morris attorney in San Diego, expects many employers will take such loans, or at least give them a very close look.

For one thing, employers would rather keep workers on if they can because it’s costly to train and bring on new employees.

“The whole point of this is really to extend an offer to employers they can’t refuse,” she said.

Paul Herber is vice president of Ascend Hospitality Group, which operates 13 restaurants in Washington state, Oregon and Utah. He said all but 40 of its 500 employees have been furloughed in the last two weeks.

One restaurant in Portland will close for good because it was already in a tenuous situation. Half of the remaining ones have takeout services, generating just 30% of normal revenue.

“The idea of loading up on debt just to keep the doors open — though it’s through no fault of our own — isn’t appealing,” he said. But if “it turns from a loan to a grant, that’s obviously the most attractive component. If that’s the case,” he added, “this would be a really helpful stimulus package.”

For large firms, including hard-hit airlines, the Senate package makes available billions of dollars in direct loans, and they are conditioned in part on maintaining payrolls.

In fact, one requirement is that businesses must keep at least 90% of the employees they had on hand as of March 24 through the end of September.

Millions of workers were let go before March 24, so some firms aren’t likely to have trouble meeting that condition. And the provision also provides a potential escape from the employment obligation in that the 90% payroll mandate must be followed “to the extent practicable.”

But there is no loan forgiveness for large firms, and the funds cannot be used for stock buybacks, something congressional Democrats as well as President Trump demanded. And loan recipients also face certain restrictions on pay and severance for executives.

For employers small and large, the legislation also provides a payroll tax credit for businesses that retain and pay employees even though their operations have been suspended or severely harmed due to the coronavirus crisis. Analysts say employers aren’t likely to be excited by this.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.