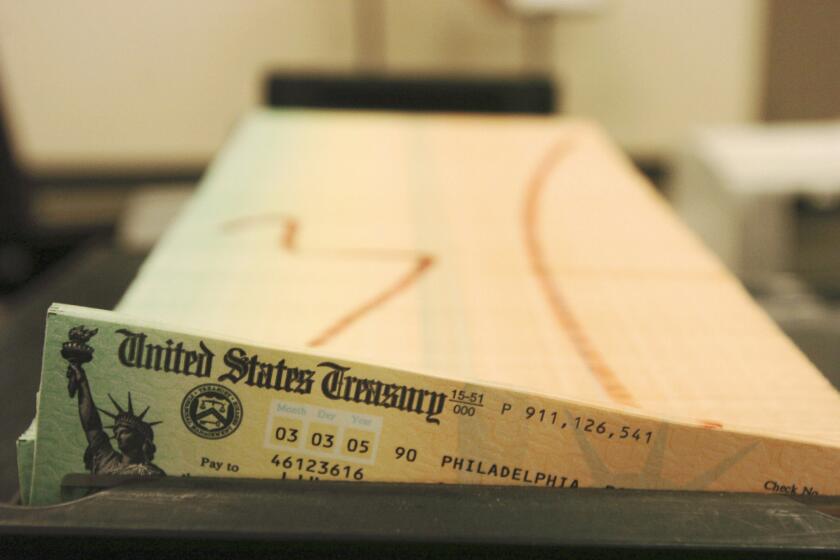

You might get $1,200 from the $2-trillion stimulus bill. What will special interests get?

WASHINGTON — In the days before the Senate unanimously passed a roughly $2-trillion bailout bill for the nation’s nosediving economy, lobbyists and special-interest groups flooded Congress with long-standing wishes and wants — though couched as urgent needs in a time of crisis.

The 880-page bill that emerged — and that the House is expected to approve Friday — did not give everyone everything they sought.

But it does include provisions plucked from the wishlists of hotels, restaurants, retailers and over-the-counter drug manufacturers, among others. Some measures will last only as long as the coronavirus crisis and its economic fallout last. Others are permanent.

One of the biggest winners could be a company whose name doesn’t show up anywhere in the relief package. Aerospace giant Boeing Co., which had struggled long before the coronavirus pandemic hit, appears the chief beneficiary of a $17-billion loan program intended for what the bill calls “businesses critical to maintaining the national security.”

Small banks won lower requirements for capital reserves, a longtime goal for their lobbyists, on the theory that it would allow them lend more money to struggling businesses.

When will stimulus checks go out? Who qualifies for a check? And other frequently asked questions.

Similarly, restaurants, grocery stores and other retailers argued successfully for a federal tax break that would let them write off renovations to their business they would otherwise have to spread out over years.

And a little-noticed provision added to the bill would speed up the Food and Drug Administration’s review of over-the-counter drugs and sunscreen products.

The provision, which has been on the Senate’s to-do list for over a year, has the backing of both physicians’ groups and makers of nonprescription drugs. But even the Public Access to SunScreens Coalition, an industry group, said protection from sunburn is not tied to the coronavirus crisis.

“It’s not controversial but it certainly caught a ride on this train,” said Steve Ellis, vice president of Taxpayers for Common Sense, a Washington-based group that highlights wasteful government spending. “People are arguing about various treatments for COVID-19, but sunscreen isn’t one of them.”

Easing the FDA’s approval process for sunscreen has been a priority for Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, who represents Kentucky, where the cosmetics company L’Oréal has a manufacturing plant. McConnell’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

Democrats also attached measures that are not directly tied to the coronavirus.

Whatever their pre-coronavirus views on budget deficits, leaders are channeling cash to households, businesses and markets, strengthening publicly funded safety nets. It may be hard to stop afterward.

The bill includes $75 million each for the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, which give grants to museums and artists.

It also provides $7.5 million for the Smithsonian Institution and $25 million for the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C.

And the long-troubled U.S. Postal Service will get a $10-billion loan, though Democrats have warned the agency will need more to stay afloat.

Businesses owned by President Trump and his immediate family, or by the vice president, top federal officials and members of Congress, are specifically barred from obtaining loans under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, known as the CARES Act. Steven T. Mnuchin, the Treasury secretary, is not empowered to lift those bans.

Still, language in the bill could allow the Trump Organization, the private holding company for the president’s businesses, to benefit from two provisions designed to help restaurants and hotels, according to the New York Times.

Other tax provisions could provide a bonanza for wealthy real estate investors, potentially including the president and members of his family.

Senate Republicans inserted a provision that would permit wealthy investors to use real estate losses to minimize their taxes. The estimated cost of the change over 10 years is $170 billion, according to the New York Times.

It’s not too late for industries whose requests didn’t make it into the final bill.

If signed into law, the bill would provide $500 billion in loans from the federal government to distressed businesses, states and local governments. The Federal Reserve, the country’s central bank, would oversee the program, an arrangement that initially worried Democrats who pressed for stronger oversight.

The loans now come with strings attached, such as disclosure requirements and oversight by a special inspector general and a congressionally appointed review board to look for waste, fraud and abuse.

Companies that borrow money under the legislation can’t engage in stock buybacks, and there are limits on how much they can increase a CEO’s pay.

Even with those efforts, the potential remains for particular industries or business owners to receive preferential treatment.

Lisa Gilbert, vice president of legislative affairs for the consumer advocacy group Public Citizen, said the legislation grants Mnuchin broad power to remove bans on profiteering with a simple waiver.

Prohibitions on stock buybacks, dividends or compensation limits can be lifted at any time. The only caveat, she said, is Mnuchin would have to appear before Congress to explain his decision.

“The single largest line item in the stimulus is the nearly $500-billion slush fund for corporations,” Gilbert said. “This money has some guardrails attached but these can be waived if Secretary Mnuchin simply chooses to.”

The bill includes funding for an inspector general to monitor the Treasury’s lending, but it’s unclear whether the office would have subpoena power, so another federal agency could refuse to hand over documents, she said.

Also noteworthy: The prohibition against golden parachutes — or generous severance packages — for CEOs may be limited to double their 2019 compensation. That could still allow a company to increase an executive’s pay by millions of dollars.

Gilbert said her organization supports the relief bill despite its flaws because it provides funding urgently needed for healthcare workers to get personal protective equipment, including masks, and much of the money will go to families as direct payments or unemployment insurance.

Reed Hundt, who led a review of economic policies during President Obama’s transition in 2008, lauded the legislation for beefing up unemployment compensation and commended Congress for not being hamstrung by fears of the deficit.

But he said the lack of transparency in the legislative process is troublesome. In the rush to deal with the crisis, there were no public hearings and little formal process.

“There is a big risk of secret favoritism,” he said. “The Treasury Department has to be completely transparent about everything it does.”

To some critics, the billions of dollars set aside to bail out Boeing, the world’s largest aircraft manufacturer, suggest the Trump administration is already playing favorites.

Aviation authorities grounded the Boeing 737 Max fleet a year ago after two deadly crashes in five months, and Boeing was in financial distress long before the coronavirus slammed the brakes on international air travel.

Partly as a result, Boeing lobbied for a bailout equivalent to the GDP of a small country. It sought $60 billion in loans, and while the Senate package set aside $17 billion for the company, Boeing could potentially receive more from the $500-billion fund.

It did not hurt that Boeing has a supporter in the Oval Office. “We’re not letting Boeing go out of business,” Trump told Fox News on Tuesday.

“Certainly this administration has not been shy about picking winners and losers and rewarding friends and punishing enemies,” Ellis said. “Once this gets in the hands of the executive, who knows how they’re going to allocate the funding.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.