The 2020 race could become the coronavirus election. Is America ready?

It’s hard to run an election during a pandemic, let alone stay healthy.

In 1918, as Spanish influenza wreaked havoc in one of the greatest health disasters in United States history, politicians were sidelined as bans on public gatherings made it impossible to hold campaign rallies.

For the record:

1:33 p.m. Feb. 28, 2020An earlier version of this story referred to the “Democratic National Convention in Milwaukee, which has seen one confirmed case of coronavirus.” The convention is in Milwaukee, but the coronavirus case was reported in Dane County, not Milwaukee County.

There was no vaccine for that virus, which killed hundreds of thousands of Americans, and the best officials could do was keep people away from each other to limit the microbe’s spread. Voters in that year’s midterm election headed to the polling booths in masks for fear that a simple act of civic participation could be deadly.

And for good reason: In Wayne, Neb., officials lifted a public-gathering ban five days before the election, allowing a flurry of last-minute campaigning — which also coincided with a rise in deadly infections.

Now, for the first time in a century, a U.S. election faces the unusual threat of being upended by a potential pandemic as a new coronavirus has shocked the global economy, tested President Trump’s administration and fueled Democratic attacks on both his leadership and the private healthcare system’s ability to protect all Americans.

Should the virus spread, experts are also raising concerns over Americans’ ability to participate in the political process should the nation undertake the kind of isolation measures that could make it more difficult to hold campaign rallies, nominating conventions and in-person balloting.

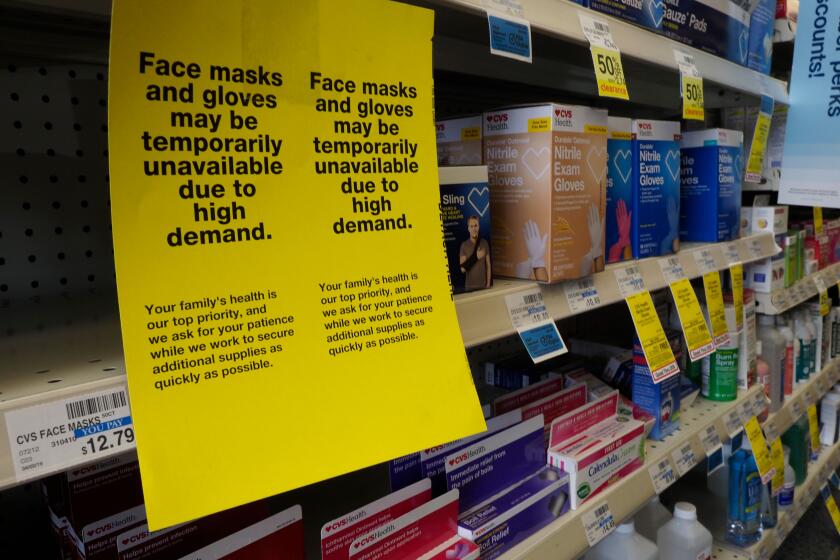

Business leaders are already canceling large conferences as a preventative matter, and American health officials are warning that disruption to daily life could be “severe,” raising questions about a pandemic’s potential impact on the nation’s democracy.

Once the coronavirus begins to spread, even those who aren’t infected will have to deal with school closures, telecommuting and other adjustments.

“If we’re unfortunate enough that the virus becomes prevalent in the United States, it could affect both campaigns and the election itself potentially, and affect how campaigns are run, affect who turns out to vote, and potentially affect even the outcome of the election,” said Richard Hasen, a professor specializing in election law at the UC Irvine School of Law.

In the best case scenario, the one still hoped for by American health officials, the virus’ march can be stopped, or at least slowed long enough for the development of an effective vaccine, which would likely take more than a year.

That would allow Americans to carry on with their lives and limit the damage to the domestic economy from the drastic isolation measures taken by China and other nations. It would prevent deaths and, as a political bonus to Trump, boost his argument for reelection.

“Because of all we’ve done, the risk to the American people remains very low,” Trump said Wednesday at a news conference with medical experts at the White House, who nonetheless warned that the virus’ trajectory in the U.S. was “uncertain” and that they were bracing for more cases.

But as evidence emerges that the virus may have gained a toehold inside the U.S. in addition to other countries, Democratic candidates have slammed Trump’s sunny outlook on containment, while also arguing that the patchwork, costly nature of the nation’s private healthcare system poses a threat to the country’s ability to manage a deadly pandemic.

Questions are raised about coronavirus testing, federal government quarantines as well as safety protocols.

“We need a president who does not play politics with our health and national security,” Democratic front-runner Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont said in a statement Thursday. He urged support for his Medicare for all plan to create a national healthcare system “so everyone can see a doctor or get a vaccine for free.”

As stories circulate of some coronavirus tests costing as much as $1,400, Pete Buttigieg, the former mayor of South Bend, Ind., said that insurance costs and coverage barriers could “get in the way of the opportunity to delay the spread of infection.”

Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts has attacked the administration’s “outrageous” refusal to promise a coronavirus vaccine would be affordable for all Americans.

In a USA Today op-ed, former Vice President Joe Biden slammed Trump’s attempted budget cuts to national health and disease-prevention agencies, which Congress has ignored by instead boosting financing for the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Former New York Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg broadcast an attack ad against Trump over his management of the virus. Fellow billionaire candidate Tom Steyer warned that Trump’s management “risks a [Hurricane] Katrina-level disaster for our country.”

A pandemic poses a unique threat to the political process. Unlike an earthquake or a terrorist attack, a pandemic is not an unforeseeable event, potentially giving officials weeks or even months to prepare. A World Health Organization official on Friday declined to call the coronavirus outbreak a pandemic, but scientists have previously said it could reach that level.

Political conventions could pose a particular risk for the spread of a virus; it’s happened before. In 2016, California Republicans had to be quarantined in their hotel rooms in Ohio after suffering from an outbreak of norovirus. Health and party officials are already monitoring the potential impact to this summer’s Democratic National Convention in Milwaukee; Wisconsin has seen one confirmed case of coronavirus.

“Our No. 1 concern is to ensure all eligible voters are able to make their voices heard without jeopardizing anyone’s health and safety,” said Maya Hixson, spokeperson for the Democratic National Committee. “We will continue to closely monitor as the situation develops.”

The Wisconsin Department of Health Services is uncertain about the virus’ potential trend in the state by July, but it said it will take the advice of the Centers for Disease Disease Control and Prevention “to keep Wisconsinites and our visitors safe and health,” said spokeswoman Jennifer Miller.

Microsoft and Facebook has both canceled upcoming conferences in California as health agencies say they are preparing for more cases.

A Republican National Convention spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment about the party’s convention in Charlotte, N.C., nor did local health officials.

Unlike other potential election emergencies, a pandemic could affect the entire country, throwing the nation’s system of locally managed elections and their protocols under harsh strain. Voting experts are calling for election officials to make pandemic contingency plans now, rather than waiting to see the progress of the virus.

“You could have 50 states simultaneously all being impacted” in a pandemic, said Michael Morley, an assistant professor of law at Florida State University College of Law who specializes in election law. He warned that the legal complexities of such a scenario could be unprecedented.

“So rather than looking at the law of a single state or a handful of states, you’re looking at the law of 50 different states, which could handle crises in 50 different ways,” Morley said.

According to the most recently available research from the National Conference of State Legislatures, “At least 45 states have statutes that deal with Election Day emergencies in some way, though there is little consistency between states on what events would be covered and exactly what plans will be followed in each emergency.”

Morley said local officials should start planning now, getting rules in place “before the emergency hits. The last thing you want is government officials, many of whom themselves are elected officials, trying to make up the rules for an election in the middle of an ongoing election.”

But the National Assn. of State Election Directors, a group that represents election officials, was mum when asked if it was examining the issue of administering elections during a pandemic.

“For questions about the coronavirus and its impact on any domestic activities, you should contact the CDC,” the group’s executive director, Amy Cohen, told The Times. The Centers for Disease Control, in turn, did not respond to a request for comment on whether it had guidance for officials making contingency plans for elections.

Another question mark would be Trump’s management of the crisis, with critics questioning his ability to manage voting issues fairly and impartially.

“What if Trump decided is what he was going to do is put a quarantine on two or three states that were likely to go the other way [and support Democrats], but not on the red states?” said Norman Ornstein, a resident scholar and elections expert at the conservative American Enterprise Institute think tank. “This raises a whole set of questions we don’t normally like to think about, but we have to think about.”

Ornstein added: “You would hope that people would act in the national interest and would put those things aside, but we’re in a time of high stakes and high tribalism.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.