Ratification of Equal Rights Amendment runs into opposition — from Trump, sure, but Ruth Bader Ginsburg?

WASHINGTON — When Virginia last month became the 38th state to approve the Equal Rights Amendment, the constitutional process launched by Congress in 1972 appeared to finally have what it needed for ratification.

It seemed fitting in 2020 to enshrine in the Constitution the principle of full equality for women on the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, which gave women the right to vote.

But the celebration has been chilled by opposition — not only from conservatives and the Trump administration, but also from Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who was a pioneering advocate for women’s equality in the 1970s.

Opponents have argued that ratification by the required 38 states has come too late — decades past the 1982 deadline set by Congress — and amid legal questions that would likely tie up the amendment in courts and erode its legitimacy.

And the dispute has become entangled in the politics of abortion. The National Right to Life Committee and some Republican lawmakers say the ERA could be wielded to strike down laws limiting abortion or barring the use of taxpayer funds to pay for abortions for low-income women.

The legislation would enshrine in the Constitution a ban on sex discrimination.

It’s unclear not only whether Virginia’s ratification is valid, but also who would make that decision. Some say it is up to Congress. Others say it is up to judges and ultimately the Supreme Court. Nevada was the 36th state to ratify, in 2017, and Illinois was the 37th, in 2018.

The Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel issued a 38-page opinion last month that told the National Archives and Records Administration it should not certify the ERA as the 28th Amendment. The archivist, who is a historian and a librarian, has the legal duty to certify and publish new amendments to the Constitution.

The opinion focused on the joint resolution adopted by more than two-thirds of the House and Senate in 1972. It said the Equal Rights Amendment shall become part of the Constitution “when ratified by the legislatures of three-fourths of the several states within seven years from the date of its submission by the Congress.” The deadline was later extended to 1982.

The text of the proposed amendment said: “Equality of rights under law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.” A second provision said Congress “shall have the power to enforce” the new amendment “by appropriate legislation.”

Twenty-two states including California ratified the ERA in 1972, and the total reached 35 in 1977. But no additional states ratified by 1982.

But in another legal twist, five states — Kentucky, Nebraska, Tennessee, Idaho and South Dakota — voted in the 1970s to revoke their ratifications. It is unclear and unresolved by the courts whether states may rescind a ratification vote.

The Justice Department said it did not matter. “Regardless of the continuing validity of the five states’ ratifications, three-fourths of the states did not ratify the amendment before the deadline that Congress set for the ERA resolution, and therefore the 1972 version of the ERA has failed ... and has expired.”

The opinion cited comments by Ginsburg that supported the idea that the window for ratifying the 1972 ERA had closed. Noting in September that the ERA “fell three states short of ratification,” she said, “I hope someday it will be put back in the political hopper, starting over again, collecting the necessary number of states to ratify it.”

On Thursday, House Democrats, led by Reps. Jackie Speier of Hillsborough and Carolyn B. Maloney of N.Y., approved a resolution to waive the time limit set in the 1972 resolution. They argue that Congress was free to include the time limit in 1972, and it is also free to lift it now. They also point out the states approved the text of the amendment, which does not contain a time limit.

But prospects for passage in the Senate are dim. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) has given no sign he will bring up the legislation.

And on Monday, Ginsburg spoke at the Georgetown University Law Center and repeated her view that the recent ratifications came too late. “There is too much controversy about latecomers,” she said in response to a question. The votes by Virginia, Illinois and Nevada came “long after the deadline passed.... I would like to see a new beginning. I’d like it to start over.”

Women’s rights advocates are reluctant to criticize Ginsburg, but they disagree with her view on the significance of the deadline.

“It is ultimately up to Congress, not the courts, to decide whether the ERA has been ratified,” said Julie C. Suk, dean for the master’s programs at the City University of New York. In two decisions early in the 20th century, the Supreme Court left it to Congress to decide whether to include a deadline for ratifying a constitutional amendment and whether to deem an amendment was ratified in a reasonable time period. “Put together, these precedents support Congress’ power to lift a deadline imposed by a previous Congress,” she said.

States on both sides of the dispute have gone to court. Two weeks ago, state attorney generals for Virginia, Illinois and Nevada sued David Ferriero, the national archivist, seeking a ruling that would declare the ERA “has become the 28th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.” In December, the state attorneys for Alabama, Louisiana and South Dakota sued seeking a ruling to prevent the archivist from “illegally adding the long-failed ERA” to the Constitution.

The abortion issue has spurred new opposition from Republicans.

“We’ve been concerned about this for a long time,” said Douglas D. Johnson, a veteran policy advisor for the National Right to Life Committee. “They used to say this was a right-wing scare tactic, but we have seen many statements recently from pro-abortion-rights advocates who say they would use the ERA as a pro-abortion legal weapon.”

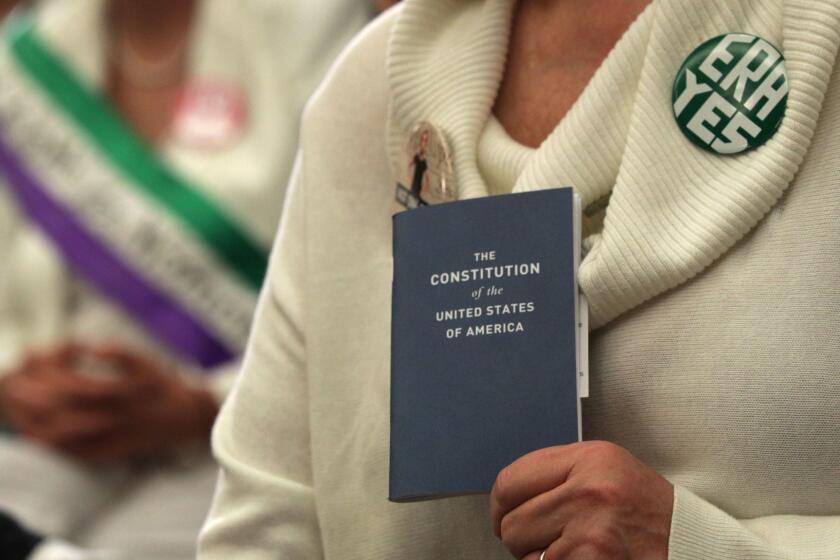

He cites as an example NARAL Pro-Choice America in its “ERA-YES” campaign. It says the amendment “would reinforce the constitutional right to abortion” and “would require judges to strike down anti-abortion laws because they violate both the constitutional right to privacy and sexual equality.”

Many others say the ERA would cap the long drive for equality for women. In 1964, Congress made it illegal for employers to discriminate based on sex. A 1972 amendment extended the ban on sex discrimination to schools and colleges, while preserving separate sports teams for girls and boys.

During the 1970s, the Supreme Court took up a series of cases brought by Ginsburg, then an attorney with the ACLU Women’s Rights Project, and struck down laws that permitted discrimination between women and men. But the justices stopped short of ruling squarely that equal rights under law may never be denied because of sex.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.