Beyond ideology: The voters torn between Bernie Sanders and Joe Biden

DES MOINES — The day after Joe Biden announced he would not run for president in 2016, some supporters in Iowa did a surprising thing: They volunteered for their second-choice candidate — Bernie Sanders.

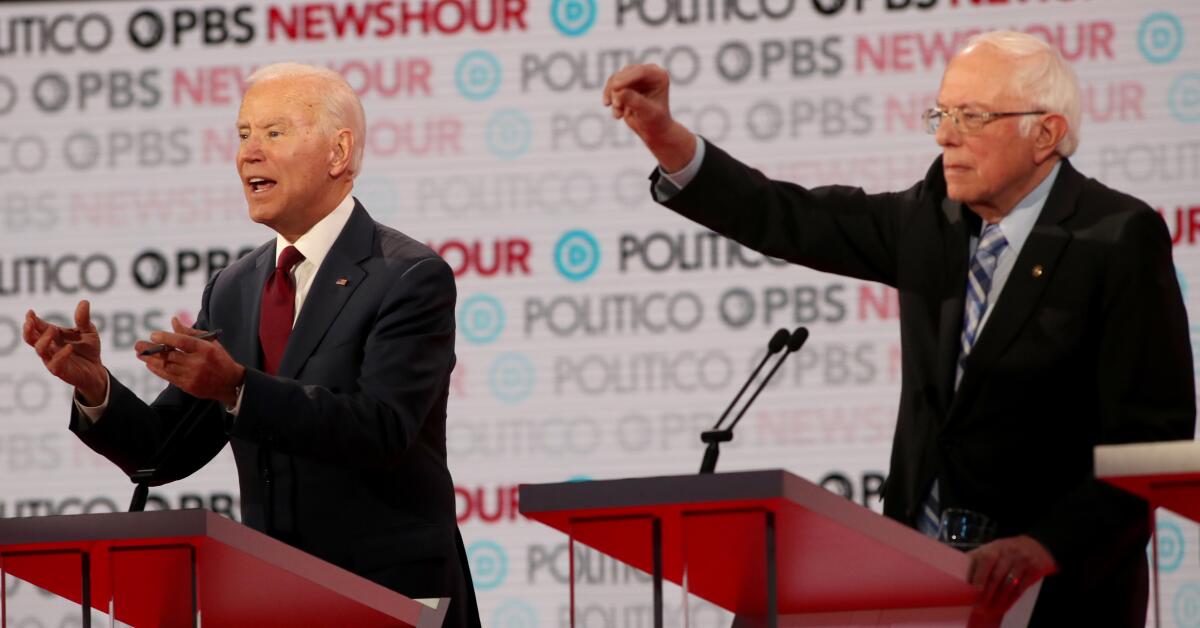

It was an early indication of a counterintuitive dynamic at work four years later, now that the two men are running against each other. They are locked in an ideological struggle for Democrats’ 2020 nomination that pits the politically moderate Biden, a classic party insider, against the liberal Sanders, a blow-up-the-system outsider. And yet they appeal to some of the same voters.

Both campaigns believe there is a swath of voters — mostly white, working-class voters, including those who voted for Donald Trump in 2016 after backing Barack Obama twice — who are torn between Biden and Sanders, the race’s old-timers. Both men’s campaigns are fishing in that electoral pond as each candidate looks to expand his base in a tight contest.

“There are a lot of working-class voters who are up for grabs, and it is increasingly Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders who they are deciding between,” said Ro Khanna, a co-chair of the Sanders campaign. “The more working class, the better Bernie does. And that is where we run into contention with Biden.”

For all the punditry about candidates competing to dominate in ideological lanes — and the recent attention on the personal feud between the left’s marquee candidates, Sanders and Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren — the competition between Sanders and Biden reflects how voters’ decision-making is often far more nuanced, and divorced from standard political labels.

“They’re both scrappy,” said Sean Bagniewski, chairman of the Democratic Party in Polk County, Iowa, which includes Des Moines. “Ideology isn’t as important as the personality. To a lot of folks, they feel like they know and can trust both Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders, regardless of the ideological stuff.”

The latest Morning Consult/Politico poll of likely Democratic primary voters nationwide found that among Biden supporters, 29% said that Sanders was their second choice, more than any other Democrat in the race. Other polls show the two candidates in competition for the lead among non-college-educated white and Latino voters.

With the rivalry among top Democrats so intense, the Sanders campaign sees a clearer path to poaching voters from the Biden coalition than to exploiting what would seem the more obvious target of voters supporting Warren, Sanders’ ideological soulmate.

“The Sanders folks realize the progressives with Warren are with her and there is no point in trying to out-progressive her,” said Patrick Murray, director of the Monmouth University Polling Institute. “They need to find voters making a decision on a dimension other than ideology.”

The Biden campaign is taking nothing for granted. It believes his edge over Sanders, as well as other rivals, is the perception that the former vice president is the most likely to beat Trump.

“When it comes to voters making up their minds, particularly in Iowa and New Hampshire, the perceived narrow ideological lanes aren’t as clear as anyone would expect,” said Pete Kavanaugh, Biden’s deputy campaign manager.

Many blue-collar Democrats attracted to Biden remain uncommitted, and their interest in what Murray calls “an old-school, working-class Democrat who fights for you” creates an opening for Sanders. “Biden and Sanders share this sense that they both came through the school of hard knocks,” he said.

For Sanders, who must expand his base of support beyond the die-hards who will be with him no matter what, that large group of uncommitted working-class voters offers perhaps his best opportunity.

Khanna noted the parallels between these men who seem to have so little in common. “Biden was born in Scranton [Pa.]. He is a person who can connect with anyone he meets. He comes off as someone who doesn’t look down at people, who is still a regular person, even though he was vice president,” Khanna said. “It is a great skill, and it is genuine.”

And Sanders, Khanna continued, grew up with immigrant parents in a rent-controlled building and is the furthest from the elites of anyone in the race, which is why farmers, factory workers and service employees in hardscrabble communities pack his events.

The Sanders campaign hesitates to revive the “beer track” label that some Washington pundits have used to describe blue-collar workers who fit the mold of the Sanders-Biden crossover voters. But it is clear those are the voters they are after.

Such voters “are looking for someone to believe in,” said Chuck Rocha, a former union officer who is a senior advisor to the Sanders campaign. “It just happens those people don’t buy a lot of wine and they don’t own a lot of lobbyists and are not really rich.” As if to punctuate the point, senior Sanders staffers arrived at last month’s Democratic debate in Los Angeles wearing T-shirts that mocked the fundraiser of another rival, former South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg. “Pete’s Wine Cave,” the shirts read.

Buttigieg is very much on what some political handicappers call the “wine track,” with supporters who tend to be college-educated and more affluent. These voters also swerve in and out of ideological lanes. Many lean toward Warren, whose platform for a vastly expanded government and wholesale economic realignment looks nothing like Buttigieg’s moderate agenda. Indeed, the crossover between the two is much like that for Biden and Sanders. A staple at Buttigieg and Warren events are voters wavering between them.

“I’m struck by how many yards have both Buttigieg and Warren signs in them,” Bagniewski said of his neighborhood in Des Moines, known as Beaverdale and home to many urban professionals. He said both candidates represented that “new generation” of leadership that attracts voters in communities like his. Warren may be 70 years old and building her movement around New Deal-style policies, he said, but “she’s seen as a progressive who might not have some of the baggage Joe Biden or Bernie Sanders or other folks might have from previous cycles.”

Warren and Buttigieg are sensitive to how their appeal is defined. For example, Warren’s feud with Sanders was sparked by a script the Sanders campaign gave to its canvassers in multiple states suggesting to voters that Warren’s appeal is confined to “highly educated, more affluent people,” and not broad enough to win in November.

Even as Sanders competes for liberal voters with the like-minded Warren, the battle with Biden for more populist working-class types goes on. In the industrial and rural communities of eastern Iowa, where voters who supported Obama twice and then crossed over to Trump are not uncommon, it is Biden and Sanders going particularly hard after votes.

The Sanders team has focused on contrasting the candidates’ records, charging that Biden has morphed from Main Street to Wall Street Democrat, one who will sell them out on Social Security and healthcare, entangle America in foreign wars and make bad trade deals.

“Biden ran as one of us, as somebody who understands the middle class,” Rocha said of Biden’s campaign theme dating to his first Senate election in 1972. The Biden of today “has not been nearly as consistent as Sen. Sanders has been.”

The Biden campaign counters by emphasizing the former vice president’s popularity across party lines, and warning that a nominee from the left could push swing voters to Trump.

It’s an argument that resonates with Des Moines retiree Bruce Koeppel, one of those volunteers who enlisted with Sanders when Biden didn’t run in 2016. Back then, Sanders’ big plans for healthcare drew Koeppel in, but this year, he cares less about policy preferences and more about backing the candidate he believes can defeat Trump.

“I like Bernie. I’ve liked him a long time, but he can’t win,” Koeppel said. “I think the vice president has the best chance to beat the president. And we have to beat the president.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.