She helped make California a clean air leader. Now Trump could upend that legacy

She has served under four governors, and has long been the force behind California’s crusade to reduce air pollution, clean car emissions and lead the United States in addressing climate change.

But in what she says is likely her last year in office, Mary Nichols, the chair of the state Air Resources Board, faces the prospect of the U.S. Supreme Court, tilted to the right by President Trump’s appointees, crippling California’s ability to set its own pollution standards. It’s the biggest threat among dozens of Trump environmental rollbacks that California is fighting in court, Nichols says, and the case that concerns her the most.

California sued the Trump administration last year after it moved to revoke the state’s waiver, one of dozens the federal government has granted over the last 50 years giving the state the authority to adopt its own pollution standards.

And while state officials say they are confident in their legal arguments, they are openly determined to prevent the dispute from reaching the Supreme Court, fearing a conservative majority could strike down the linchpin of their air pollution and climate change policies.

As a result, Nichols and California Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra have settled on a strategy of trying to outlast Trump, in the hope that he will lose reelection and that the next president will drop the case.

“Our strategy is to win, but to win in a way that does not precipitate a Supreme Court taking of this case until Mr. Trump is out of office,” Nichols said in an interview in December at a cafe near her Los Angeles home. “There’s nothing secret about that. We think that a new administration is likely to change position.”

California’s go-slow approach contrasts with its aggressive resistance to Trump’s efforts to weaken clean air, water and climate change regulations. The state has filed dozens of environmental lawsuits challenging the administration’s rollbacks. The Air Resources Board alone is involved in more than 20 ongoing cases against the administration.

Legal experts said the state’s reluctance to put the case before the Supreme Court is logical.

“The current Supreme Court, especially after the confirmation of Justice [Brett] Kavanaugh, is not considered a friendly venue for proponents of environmental regulation, so they try to stay away,” said Michael Gerrard, director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University.

Defeat could undo some of the legacy of Nichols, 74, who has spent decades working to clean California’s air, in state and federal government and as an environmental lawyer at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Her legal expertise, political savvy and skill at implementing tough regulations is widely credited with making the state an international leader in fighting climate change.

Appointed by Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger in 2007, Nichols has overseen the powerful Air Resources Board’s evolution from a smog-fighting agency to one charged with limiting carbon emissions from one of the world’s largest economies.

“She is the smartest and most effective regulator of auto pollution anywhere in the country and possibly in the world. She’s been dealt a difficult hand by Trump,” said Dan Becker, director of the Safe Climate Campaign, which advocates for tough action against global warming. “Probably the most important part of her legacy is: Will California continue to be the nation’s, and often the world‘s, leader in fighting auto pollution?”

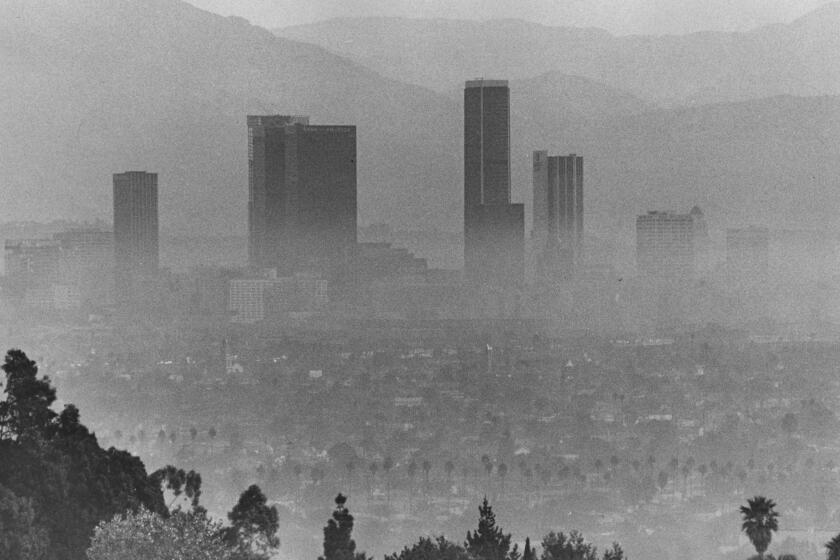

If the Trump administration triumphs in court, California would lose a powerful tool that it has relied on for decades to clean the nation’s worst smog and reduce people’s exposure to health-damaging emissions. Without it, regulators warn that millions of Californians could be forced to continue breathing unhealthy air. Alternately, California might have to compensate by imposing more onerous measures, such as banning gas-powered vehicles.

A few months into his presidency, Trump announced plans to roll back nationwide fuel economy standards adopted by the Obama administration and California with the aim of getting the nation’s cars and trucks to average more than 50 miles per gallon by 2025. The administration in 2018 released a proposal that would freeze the standards at 37 mpg, but has not acted to finalize it.

Of much greater concern to California regulators than that rollback is the administration’s move to take away California’s power to set such standards in the first place. Last fall, the White House formally revoked the federal waiver granted in 2013 by the Obama administration, which allows the state to set its own greenhouse gas emissions standards for cars and light trucks and to require automakers to sell zero-emission models. California and nearly two dozen other states filed suit in September, soon after that decision.

If California’s strategy is to run out the clock, the administration’s tactic appears to be to put the case before the Supreme Court as quickly as possible.

On Dec. 18, the Department of Justice asked a federal appeals court to fast-track its unprecedented bid to revoke California’s ability to set its own car emission standards. Lawyers for the federal government argued that a slower timeline would “unduly burden the automotive industry, whose interests here — given the industry’s size and importance to the national economy — strongly compel expedited consideration.”

“We have been seeing this happening a lot,” said Maya Golden-Krasner, a lawyer for the Center for Biological Diversity, which has also sued the administration in defense of California’s authority to set its own car pollution rules. “The Trump administration thinks this court is in their pocket, so they’ve been trying to expedite cases as quickly as possible.”

A Department of Justice spokesman declined to comment on the case, citing a policy of not discussing ongoing litigation.

California and a coalition of supportive states have filed two lawsuits to stop the Transportation Department and the Environmental Protection Agency from revoking the legal waiver that allows the state to set stricter auto pollution and greenhouse gas emission regulations.

The first case, filed in Federal District Court in Washington, strikes at the administration’s argument that California shouldn’t be able to write its own rules. The second case deals with the waiver itself and was filed in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

Federal government lawyers are trying to move the first case to the appellate court as well, leapfrogging the lower court. California lawyers want it to stay in the district court, which still has a majority of Democratic appointees among its active judges.

Both of these cases may eventually reach the Supreme Court.

While Atty. Gen. Becerra’s office would not comment, other California officials and environmentalists said they hope the cases never make it that far.

“We don’t want to go to the Supreme Court because there’s always a risk when you enter into those marbled halls that something bad will happen,” Nichols said. “We think it’s a very strong argument. It’s not that we are worrying about the state of our legal case. It’s just that there’s always a risk.”

A meeting with Gov.

Nichols was first appointed to the Air Resources Board in 1975 by Gov. Jerry Brown during his first term. She was one of Brown’s close allies and he kept her as chair when he returned in 2011. Under her leadership, the agency has pioneered a range of climate and clean air initiatives, including cap-and-trade, which aims to cut greenhouse emissions across industries, a low-carbon fuel standard to clean cars and trucks, and sales mandates to increase the number of electric vehicles on the road.

When Gov. Brown was leaving office, Nichols said she had assumed Gov. Gavin Newsom would replace her, but he too asked her to stay. With a political fight with the Trump administration in full swing, Nichols said she wanted to project stability and “not to send any messages other than one of steady as she goes.”

But Nichols said she does not want to be reappointed after her term concludes at the end of this year.

“The time for me to pass the torch has come,” she said.

David Pettit, an attorney for the Natural Resources Defense Council who has known Nichols for decades, said it “must be really galling” to be playing defense on seemingly settled issues so close to her departure.

“It’s created a huge amount of uncertainty in a time when we need to be moving ahead on climate change, not backward,” he said. “It seems crazy to me that we’re in that position now.”

There’s no guarantee the Supreme Court would agree to hear the cases on California’s authority to regulate vehicle emissions and, if it did, it’s highly unlikely that would take place before the 2020 presidential election.

“Our focus is on ensuring that all issues get a full, careful airing — and on a standard litigation calendar, that will likely take much of next year,” Air Resources Board spokesman Stanley Young said.

Still, California and environmental groups have reason to be concerned.

If the appellate court decides in favor of the administration, California would have little choice but to ask the Supreme Court for a stay, keeping the state’s stricter standards in place while the court decides whether to hear its appeal. Hoping the current court intercedes to shield its climate policies is not a position the state wants to be in.

Nichols said she had no Plan B if the nation’s highest court takes away California’s power over vehicle emissions.

California and local governments could resort to other measures, she said, including bans on gas-powered vehicles in congested areas or “other actions that would make it more difficult to drive or operate the most inefficient and polluting cars.”

Gina McCarthy, a former EPA administrator under President Obama who took over this week as head of the Natural Resources Defense Council, one of the groups challenging Trump’s revocation of California’s waiver, said “if this administration thinks they can win by intimidating, out-thinking or out-litigating Mary Nichols and her staff, they will be sorely disappointed.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.