Congress braces for Trump impeachment vote as partisan lines harden

WASHINGTON — The nation’s fractured leadership continued its somber march into the history books as the House of Representatives prepared to impeach President Trump on Wednesday, a dramatic step that has been sapped of almost any drama by relentless partisanship, creating a sense of inevitability around an otherwise monumental constitutional clash.

With the congressional machinery grinding toward a searing rebuke of his presidency, Trump lashed out at House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, the architect of the proceedings, in a six-page letter denying any wrongdoing on the eve of the vote.

“You are making a mockery of impeachment and you are scarcely concealing your hatred of me, of the Republican Party, and tens of millions of patriotic Americans,” he wrote in a screed that veered from grievance to grievance, echoing his increasingly frequent tweets, but under a presidential letterhead.

No Republicans are expected to vote for impeachment, and Democrats anticipate only a handful of defections at most. Many Democratic moderates who represent congressional districts that Trump carried in the last presidential election have announced they will vote yes, a sign that party lines have hardened like concrete around Capitol Hill.

The greatest mystery was whether long-winded speeches and procedural maneuvering would delay the vote until Thursday. What is all but certain is that Trump will become the third president in U.S. history to be impeached and, next month, the Republican-controlled Senate will refuse to remove him from office.

The ultimate impact of the impeachment saga awaits next year’s election results and, eventually, the verdict of historians. For now, national polls show public opinion has barely budged in either direction, with Americans divided down the middle, mainly by party.

Although Pelosi (D-San Francisco) once said impeachment should be a bipartisan undertaking, she said in an interview with The Times on Tuesday that the gravity of the president’s misconduct made her willing to push forward without any Republican support.

“If they are not going to honor their oath of office, I cannot join them in that,” Pelosi said. “And that’s what they have decided to do.”

Impeachment inquiry

What else you need to know

The prep, promises and drama of the Senate impeachment trial

The key players and terms to be familiar with

A timeline of how we got here

How impeachment works

Our full coverage of the inquiry

Democrats argue that Trump violated his oath of office by asking Ukraine to launch investigations that would benefit him politically, a request made while the president was withholding nearly $400 million in security aid for the Eastern European country as it faces Russian aggression. They put forward two articles of impeachment, one for abuse of power and the other for obstruction of Congress because Trump directed administration officials to ignore subpoenas seeking documents and testimony.

“There’s no question that it’s a very sober moment, but I would say that I feel such a profound obligation to register my support for impeachment because the president has shown such contempt for the rule of law. And his willingness to continue this criminal activity is pretty obvious, and he has to be reined in somehow,” said Rep. Jackie Speier (D-Hillsborough).

Republicans have largely ignored or denied the evidence compiled by Democrats, instead complaining about the process and accusing them of desperately trying to undermine a president they couldn’t beat at the ballot box.

“The Democrats’ impeachment inquiry has been flawed and partisan from Day One,” Rep. Tom Cole (R-Okla.) said. “So I guess it should come as no surprise the Democrats’ preordained outcome is also flawed and partisan.”

Trump declined to participate in the impeachment process by presenting evidence or allowing top officials to testify, yet he complained in his letter to Pelosi that he was provided less due process than “those accused in the Salem Witch Trials.”

Once the House Intelligence Committee issued its report on the Ukraine scandal early this month, the House Judiciary Committee finalized articles of impeachment against the president during a handful of hearings. As the minority, Republicans had no chance of stopping the process.

“It’s just something that we’re having to plow through at this point,” said Rep. Doug Collins (R-Ga.), the ranking member on the Judiciary Committee. “They have the votes. And they’ll move it forward.”

The last steps before the articles of impeachment reached the House floor occurred Tuesday at the House Rules Committee, an otherwise obscure panel responsible for laying out the guidelines for House debate.

Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-Md.), who presented the Democrats’ case at the hearing, said Trump had elevated “the personal interests and ambitions of the president above the common good, above the rule of law, and above the Constitution.”

Noting that the president had asked Ukraine to investigate former Vice President Joe Biden, his potential opponent in next year’s campaign, Raskin said Trump had invited foreign interference into a U.S. election.

“You have everything the framers were concerned about tied up in one bundle here,” he said.

Collins, who spoke on Republicans’ behalf during the hearing, did not concede that Trump had done anything wrong.

“The president is well within his right to do that,” he said.

Assuming the House votes to impeach Trump, there will be no respite from partisanship once the matter moves to the Senate, which is planning to hold a trial in January.

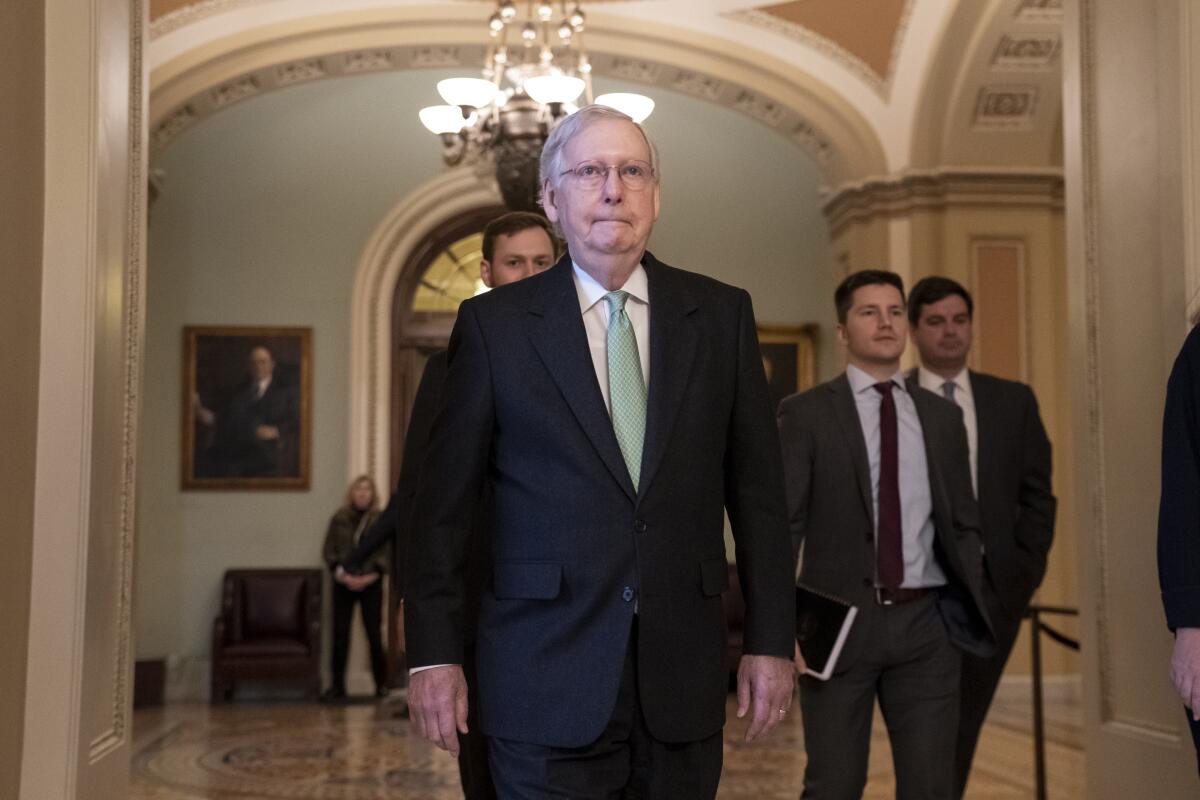

“I think we’re going to get an entirely partisan impeachment. I would anticipate almost an entirely partisan outcome in the Senate as well,” Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) told reporters on Tuesday.

Removing an impeached president requires a two-thirds vote in the Senate, and Republicans hold a majority, making such a step highly unlikely.

McConnell rejected a proposal from Minority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.) to call witnesses during the trial. Arguing that it was the Democratic-controlled House’s responsibility to make the case for removing the president, McConnell said there was no reason for further investigation.

“It’s not the Senate’s job to leap into the breach and search desperately for ways to get to guilty,” he said on the Senate floor. “That would hardly be impartial justice.”

Schumer wanted Mick Mulvaney, Trump’s acting White House chief of staff, and John Bolton, his former national security advisor, to testify, among others. Neither of them spoke to the House during its investigation, but Democrats believe they have relevant information about the president’s behavior based on other witnesses’ testimony.

Trump blocked Mulvaney from testifying to the House, and Bolton said he would only participate if forced by a federal court. Democrats did not push the issue, given the time that a legal challenge would entail.

“What is Leader McConnell afraid of? What is President Trump afraid of?” Schumer said to reporters. “The truth? The facts?”

Times staff writers Jennifer Haberkorn and Sarah D. Wire contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.