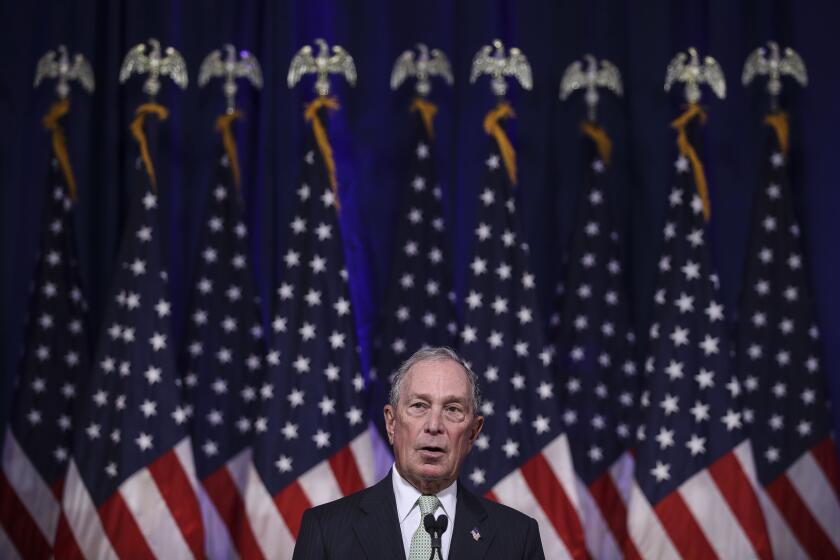

Have you seen Michael Bloomberg during ‘Jeopardy’ or NFL games? He’s spending millions to make sure you do

Television viewers in Southern California can hardly miss the ads promoting Michael R. Bloomberg for president this holiday season.

On Sunday, the former New York City mayor ran two commercials on CBS during the NFL game between the Minnesota Vikings and Los Angeles Chargers, then another during “60 Minutes.” A Bloomberg spot also aired in prime time during “The Sound of Music” on ABC.

Soap-opera fans saw the Democrat’s ads last week during “General Hospital” and “Days of Our Lives”; game-show devotees during “Jeopardy” and “Wheel of Fortune.” On Friday alone, L.A. broadcast stations showed Bloomberg ads about 80 times.

The scale of the billionaire’s advertising for California’s March 3 election is unprecedented for a Democratic presidential primary, campaign veterans say. In the three weeks since he announced his candidacy, he has spent more than $5.4 million on broadcast television ads in the Los Angeles media market alone, station logs filed with the federal government show.

He has put millions more into broadcast TV spots in the San Francisco, San Diego, Sacramento and Fresno markets, along with digital and cable advertising. None of Bloomberg’s rival Democrats have the wherewithal to come even close to matching his flood of ads in California, America’s most expensive state for TV advertising, and he appears set to sustain it for a full three months.

Nationwide, Bloomberg has already dropped $117 million on advertising, including $13.6 million in California, surpassing all of his Democratic opponents combined, according to Advertising Analytics, a firm that tracks political ad buys. Defying tradition, he is all but skipping the four states that open the party’s 2020 nomination battle with contests in February.

As opponents plow enormous time and resources into Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada and South Carolina in hopes of gaining early momentum, Bloomberg is leaping ahead to the bigger states that start voting in March.

Tapping his personal fortune — Forbes puts his net worth at $55.7 billion, making him one of the richest people in the world — Bloomberg is saturating the TV airwaves with ads not just in California, but also in the 13 other states with contests on Super Tuesday and more than a dozen others that vote later in March.

Even if a clear front-runner emerges from the four early states, that candidate will almost certainly be outspent by Bloomberg in cities where TV advertising is costly — Dallas, Houston, Chicago, Miami, Cleveland, Atlanta, Seattle, Boston, St. Louis and Detroit, among many others. And nobody will have his head start.

“Certainly it helps to have the ability to communicate a message broadly,” said Dan Kanninen, who is overseeing the state-by-state campaign operations that Bloomberg has begun setting up from coast to coast. “It’s something that’s unique. People have not tried to run a national campaign in this way.”

About 2% of Democratic delegates will be awarded in the first four states; 65% will be allocated in the contests that take place in March, Kanninen said.

Much of Bloomberg’s advertising runs during news and talk shows. In Los Angeles, he has paid $2,000 each time his 30-second spots aired during NBC’s “Today” show.

Prime time is far more expensive. The spots shown Friday during “Hawaii Five-0” and “Magnum P.I.” on CBS each costs $12,000 to run just in L.A. The 30 seconds during “60 Minutes” came to $30,000. Popular sports programs are even costlier. Bloomberg booked two commercials during the Vikings-Chargers game. The price each time was $45,000.

Many know little to nothing about the former New York City mayor. Others have concerns about his vast wealth.

Bloomberg’s ads highlight his fights against guns, tobacco and coal. They describe him as a stable leader tough enough to beat President Trump.

National polls suggest the ads are having some effect. Bloomberg registers about 5% support among Democratic primary voters, according to Real Clear Politics, a nonpartisan website that aggregates poll results. He trails former Vice President Joe Biden, Sens. Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, and Pete Buttigieg, the outgoing mayor of South Bend, Ind., but he’s ahead of the rest of the candidates, who have been campaigning for roughly a year.

Several Democratic opponents say Bloomberg and Tom Steyer, the other billionaire in the race, are trying to buy the presidency.

“I don’t think America looks at the guy in the White House and says, ‘Let’s find someone richer,’” Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar recently told ABC’s “The View.”

Bloomberg, who faced similar accusations in his mayoral campaigns, suggests his wealth protects him from the corrupt influence of donors.

“I’m doing exactly the same thing they’re doing, except that I am using my own money,” he told “CBS This Morning.” “They’re using somebody else’s money, and those other people expect something from them. Nobody gives you money if they don’t expect something, and I don’t want to be bought.”

Bloomberg spent a total of more than $260 million on his 2001, 2005 and 2009 campaigns for mayor and won all three elections.

“It’s his classic playbook, and it succeeded before, particularly in the first race when no one thought he had much of a chance,” said Bill Carrick, a Los Angeles Democratic consultant. “I think presidential campaigns are really a hell of a lot more complicated.”

Michael Bloomberg sat stone-faced behind an ornate desk at City Hall, as speaker after speaker berated him for four and a half hours.

Beyond the challenges of appealing to diverse voter groups and mastering the Byzantine sequence of primaries and caucuses that allot delegates, candidates inevitably face trouble shaping the way they are covered by the media. In a presidential race, news stories can blunt the effect of advertising.

TV commercials are also less important than they used to be as more Americans turn to social media and websites as their main sources of information about candidates.

Nonetheless, it remains for now the most effective way to communicate with the public, especially older people who tend to be the most reliable voters.

After South Carolina’s primary on Feb. 29, the race for the Democratic nomination will instantly expand into a national race, with Super Tuesday coming three days later. The March 3 contests include California, Texas, Virginia and Colorado. The primaries later that month include Florida, Illinois, Ohio and Georgia.

The biggest prize is California; 416 of its 495 delegates will be up for grabs on March 3. A party formula will spread them among candidates who win at least 15% of the vote statewide and in each of the state’s 53 congressional districts.

California’s vast size can make it prohibitively expensive for candidates to advertise in its major media markets. Apart from Bloomberg, the only other Democrat to run ads in the state so far — but at a much lower volume — is Steyer, who made his fortune running a hedge fund in San Francisco.

Nationwide, Bloomberg has already spent more than double what Steyer has, according to Advertising Analytics. Forbes lists Steyer’s net worth as $1.6 billion.

Bloomberg’s late start in the presidential race left him little choice but to bypass the early-voting states and start advertising heavily on the assumption that Democrats will not yet have a clear favorite by Super Tuesday, said Rob Stutzman, a California Republican consultant.

“The only path for him is to build up credibility, likability and [name] identification,” said Stutzman, who was a top campaign advisor to former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger and billionaire Meg Whitman, the GOP’s failed candidate for governor in 2010.

Whitman, who was endorsed by Bloomberg, a former Republican, is part of a large stable of rich candidates whose lavish personal spending was not enough to win statewide office in California. She spent $178.5 million on her campaign, including $144 million of her own money, only to finish 1.3 million votes behind Jerry Brown.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.