Lawmakers are studying ‘what’s impeachable.’ Do you know?

WASHINGTON — Rep. Ted Lieu (D-Torrance) is listening to every impeachment podcast he can as he drives around his district. Rep. Mike Levin (D-San Juan Capistrano) catches up with news clips at the end of each day and watches snippets from the Intelligence Committee’s public hearings on his flights back and forth from Southern California.

Rep. Salud Carbajal (D-Santa Barbara) pores over a white binder with every scrap of impeachment information his staff can find. He wants the research categorized and annotated as he prepares for one of the biggest decisions of his life, whether to impeach President Trump.

“I’m trying to devour as much as I can within the limited spare time that I have,” Carbajal said. “I’m trying to be as thorough and as educated as I can, because it’s that important of an issue.”

Congress’ probe of Trump’s actions toward Ukraine and whether they justify impeaching him is quickly moving into a new phase this week as the action shifts to the House Judiciary Committee. That panel is scheduled to start formal impeachment proceedings Wednesday with a hearing featuring constitutional law experts designed to educate members on what exactly is impeachment and what actions by a president merit that punishment.

The hearing provides a tacit acknowledgment that many people — even members of Congress — may not fully grasp what impeachment is. So before the next steps begin, let’s review.

Who will House Judiciary Committee members hear from?

The committee is bringing in four experts, Noah Feldman, a Harvard Law professor; Pamela Karlan, a Stanford law professor; Jonathan Turley of George Washington University law school and Michael Gerhardt, a law professor at the University of North Carolina.

Feldman has argued that an actual crime is not necessary to impeach a president and has written in opinion columns that Democrats have legitimate grounds to impeach Trump because he has abused the power of his office.

Karlan is a former Obama administration Justice Department official who has not been vocal about the impeachment proceedings. She is well known in legal circles for her work of voting rights and political processes and has argued several cases before the Supreme Court. Karlan was a law clerk for Justice Harry Blackmun.

Gerhardt, a former Al Gore campaign official, gave a similar presentation to Congress when the Judiciary Committee was considering impeaching Clinton. His book “Impeachment: What Everyone Needs to Know” describes itself as a nonpartisan “primer for anyone eager to learn about impeachment’s origins, practices, limitations, and alternatives.”

The one expert called by Republicans, Turley has written extensively about Trump and impeachment and has criticized Democrats’ for moving too quickly and being too narrowly focused in the impeachment process.

Although committee panels in Congress normally feature more witnesses called by the majority party than the minority, Republicans say they are upset they were allowed to call only one expert. In a letter Monday, Rep. Doug Collins (R-Ga.) asked Judiciary Committee chairman Rep. Jerrold Nadler (D-N.Y.) to expand the panel and let the minority party call the same number of witnesses as Democrats. He pointed out that 19 academics with a range of opinions were called to educate members during the Clinton impeachment. Nadler has not responded.

What will they say?

Nadler said in a statement announcing the hearing that the point of the hearing is to “explore the framework put in place to respond to serious allegations of impeachable misconduct like those against President Trump.”

Expect a lot of talk about what the framers of the Constitution intended when they created impeachment, what they meant by the phrase “high crimes and misdemeanors,” what standards Congress should use as it examines the evidence, and whether the accusations against Trump rise to the level of impeachment.

Why does Congress have this power anyway?

Having just thrown off a monarchy, the writers of the Constitution were concerned about giving too much power to the executive, the position now known as the president, and having no recourse if that power were abused. So, at the very end of Article II of the Constitution, which set up the executive branch, they inserted 31 words that would give the legislative branch power to try, convict and remove a president, or certain other federal officials, for “treason, bribery or other high crimes and misdemeanors.”

The writers of the Constitution didn’t want to tightly define high crimes and misdemeanors but gave broad examples of what it should include. Legal experts describe it as an offense against the public trust at large, not necessarily a crime defined by law.

James Madison wrote in 1787 that there had to be a way to defend against “incapacity, negligence or perfidy of the chief executive” because the president might “pervert his administration” or “betray his trust to foreign powers.” Alexander Hamilton described the standard in 1788 as “abuse or violation of some public trust.”

Legal experts also stress that this punishment was not intended to be used when Congress disagrees with the president’s policy decisions. (This is why Pelosi and other Democratic leaders have refused to bring articles of impeachment against Trump for policies they don’t like, such as family detention at the southern border.)

Impeachment is an Americanization of British and Colonial law that allowed parliament to police political offenses that subverted the government or public trust, though not those committed by the crown. The Americans narrowed the list of what offenses could be impeachable and expanded it to include the head of government.

Does the evidence against Trump warrant impeachment?

That is up to the 435 representatives in the House.

Individual House members have to decide whether the evidence collected rises — in their opinion — to the level of impeachment. The Constitution set no standard of evidence that has to be met like the “reasonable doubt” standard in the judicial system, though legal experts have suggested a standard closer to a preponderance of evidence, also known as probable cause.

During the Clinton impeachment hearings, the House Judiciary Committee was reluctant to set any formal burden of proof, stressing that it had “clear and compelling evidence,” but that such a finding wasn’t required.

Similarly it’s up to individual senators to decide if the evidence the House presents warrants removal from office. Even though the proceeding is called a trial, it is not a criminal proceeding. There’s no specific standard of evidence that has to be met as there is in the judicial system. Counsel for presidents in previous impeachment cases have argued that the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard used in criminal cases should also be the standard senators adopt; House managers who have presented impeachment cases have argued for a lower standard.

Pop quiz. Does impeachment mean removal from office?

Nope (it’s a common misconception). Think of impeachment as similar to having charges brought against the president. The Senate holds the trial and decides whether to remove the president.

The Senate has never removed a president. Presidents Bill Clinton and Andrew Johnson were impeached by the House, but not convicted by the Senate. Each finished his term.

With a Republican majority, the current Senate is unlikely to get the two-thirds vote necessary remove a Republican president.

As a whole, the process doesn’t often lead to removal from office. The House has impeached 19 individuals: 15 federal judges, one senator, one Cabinet member and two presidents. The Senate has convicted just eight of them, all federal judges.

Can the Supreme Court overturn the Senate if it convicts or stop the House from impeachment?

President Trump has tweeted a few times that the Supreme Court should step in to stop the impeachment proceedings, but the framers of the Constitution specifically sought to keep this from happening. They put the power to remove a president solely in the legislature’s hands.

The Supreme Court backed that up in 1993 when a federal judge from Mississippi challenged his removal. The Constitution makes impeachment “a bridle in the hands of the legislative body upon the executive branch,” the court said.

One caveat is that the Senate proceedings are overseen by the chief justice. That keeps the vice president, who is normally the presiding officer of the Senate, from overseeing a trial that could potentially elevate him to the presidency.

What else do you need to know before the hearing?

It could be a long day. The Judiciary Committee is one of Congress’ largest committees, and every representative gets a chance to ask questions.

The resolution that sets the ground rules for impeachment gives the chairman and ranking members, or a designated staff member, up to 45 minutes to ask questions at the beginning of the hearing. If you don’t normally watch committee hearings, it’s worth knowing that high-profile hearings — especially ones with some of the most conservative and liberal members of Congress like this — can devolve quickly into speechifying and pontificating as some committee members try to get attention during their five minutes of questions. Setting aside up to the first hour and a half for concentrated, direct questioning allows the chairman to set the tone for the entire hearing.

After that, all 41 members of the committee get their five minutes. If they all stick to that time limit (a big if) that’s an additional three hours and 40 minutes of questions.

And it’s just the first day

Further impeachment hearings haven’t been scheduled yet, but at least a few more are expected.

The committee held multiple hearings over six months when considering articles of impeachment against Nixon. It held four hearings in two days before voting on articles against Clinton.

The Intelligence Committee report has to be introduced and weighed in some way by the Judiciary Committee, likely with a presentation of the facts by the committee’s staff counsel who did much of the witness questioning in that committee. The Judiciary Committee will also look at Republicans’ rebuttal.

The Judiciary Committee could call witnesses to testify, and Republicans on the committee have the option to call witnesses or offer evidence of their own, though only if a majority of committee members agree.

So far, Trump has refused to cooperate with the investigation or allow high-ranking officials to comply with subpoenas for testimony or documents, and his lawyers turned down an invitation to participate in Wednesday’s hearing. That could change, and they still have the ability to participate in future hearings and question witnesses if the president changes his mind.

If the Judiciary Committee recommends articles of impeachment, then the House will debate them and hold a vote.

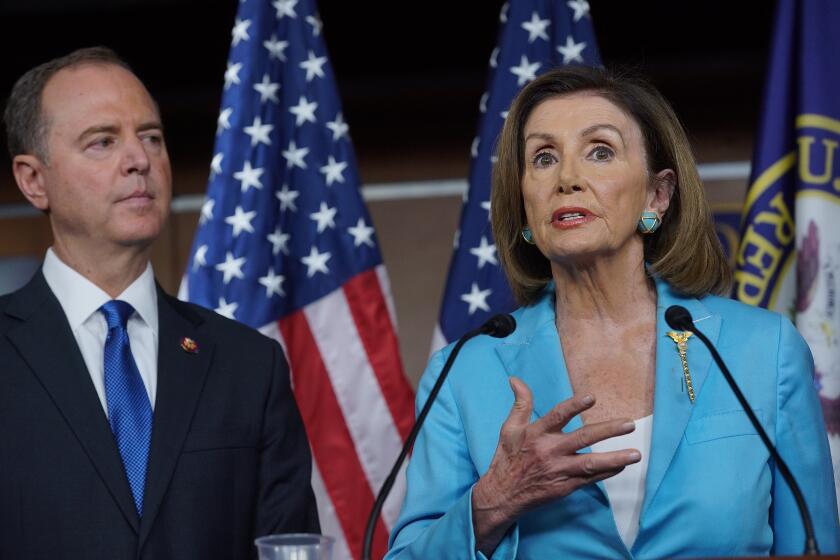

Speaker Nancy Pelosi insists there is no timetable for impeachment, so there is a chance this could slip into 2020. Still, Democratic leaders are thought to want the process wrapped up before Christmas, so a whirlwind two and a half weeks could be ahead.

Then it’s time for a Senate trial, which could last weeks, but that’s a story for another day.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.