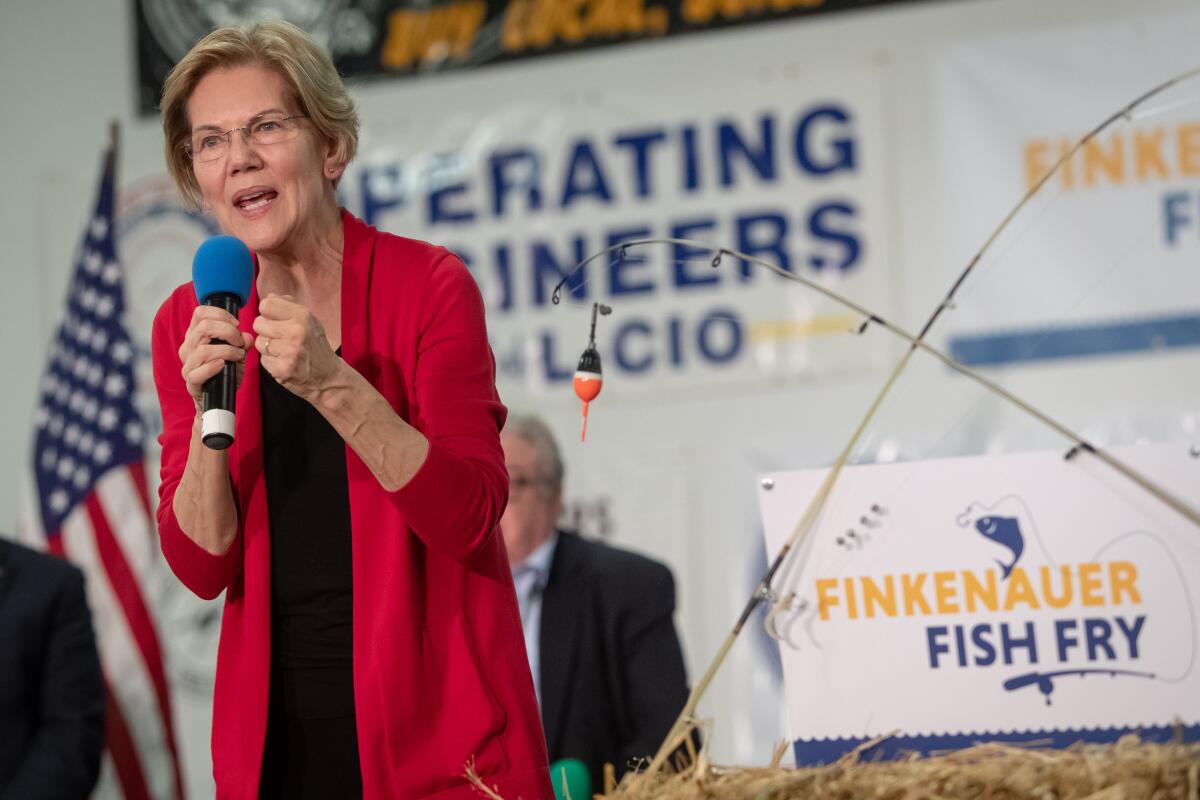

Elizabeth Warren’s pivot on ‘Medicare for all’ shows the tricky politics of healthcare

WASHINGTON — Last spring, at the dawn of the endless Democratic primary debates, it seemed as if presidential candidates couldn’t wait to endorse the idea of “Medicare for all.”

It was a fine slogan, even if they didn’t agree on what it meant. Everyone likes Medicare; every Democrat wants to move toward universal health coverage. What could go wrong?

Only this: Bernie Sanders had already written a detailed healthcare bill — and in it, Sanders laid claim to sole ownership of Medicare for all.

Sanders’ version of national healthcare is expensive and ambitious. It would abolish private health insurance, cover much more than Medicare does now, and raise middle-class income taxes to pay for it. It’s hard to imagine Congress considering it.

Other candidates were hit with a predictable question: Do you support Sanders’ bill, including the abolition of private insurance?

Elizabeth Warren boasted of having a plan for everything else, but she outsourced this one.

“I’m with Bernie,” she said.

Kamala Harris agreed, saying she wanted to “eliminate” the hassle of dealing with insurance companies.

Cue the backlash. It turned out that progressive activists who attend Democratic town halls are ready for Canadian-style government insurance, but millions of other voters aren’t.

Polls found that most voters thought Medicare for all meant everyone would be allowed to opt into Medicare if they wanted, not that private health insurance — the kind most Americans buy through their employers — would disappear.

They also weren’t keen on paying more in federal taxes, even though Sanders and other advocates argued that they’d save money on premiums and other healthcare costs in the end.

The moderate candidates pushed back. Joe Biden proposed a more gradual route toward universal coverage, a government-run public option that anyone could choose to buy, and that he said would be “like Medicare.”

Pete Buttigieg proposed a similar plan and dubbed it “Medicare for all who want it.” Both said they’d allow people to keep private insurance.

After weeks of waffling, Harris came up with hybrid: a government-run plan with private insurance as an option, similar to the role “Medicare Advantage” plays in the current Medicare system.

Oddly, Harris’ plan resembles present-day Medicare more closely than Sanders’, which would change Medicare into something much bigger.

On Nov. 1, Warren belatedly offered details of how she’d finance a Sanders-style Medicare for all through more than $15 trillion in new taxes on businesses and the rich. But that didn’t stop the criticism.

So last week, she backpedaled.

In the great debate between Sanders’ big leap to a single government-run health plan and Biden’s incremental steps toward broader coverage, Warren declared herself in favor of both.

She’s still in favor of Sanders’ plan. But she acknowledged that it would take a while to get through Congress. That’s if she can pass it at all — although she doesn’t say that part out loud.

So Warren proposed fast-track legislation in the interim to make traditional Medicare available to everyone over 50 and create a Biden-style public option plan available through Obamacare. She calls this the “Medicare for all option,” which sounds a lot like Buttigieg.

Meanwhile, she promises, she’ll try to pass a full Sanders-style bill later, probably in the second half of her first term.

By then, she said, “the American people will have experienced the full benefits of a true Medicare for all option,” and public support will be stronger. Never mind that most new presidents have more sway in their first two years in office, rarely years three and four.

Needless to say, Warren took flak from both sides.

Sanders, in Los Angeles, said he’d turn his plan into law right away — implying that Warren’s strategy is too slow.

A spokeswoman for Biden accused Warren of “double talk.” A spokeswoman for Buttigieg said Warren still “wants to force 150 million people off their private insurance, whether they like it or not.”

It’s true that Warren’s plan calls for abolishing private insurance and imposing huge new taxes — and voters aren’t sold on those ideas.

But Warren’s new plan is smart for one big reason: None of these proposals was ever going to sail through Congress — not even the relatively moderate Biden plan.

The Democrats’ debate on healthcare has suffered from a bad case of fairy dust.

They’ve argued plenty about policy — about how they want to change the nation’s health system and how they’d pay for it.

But their progressive candidates sometimes sound as if they’ve forgotten basic politics: Which proposal will help them win the White House? And how will they get it through a Congress in which Republicans might retain a majority (or at least a near-majority) in the Senate?

No president’s agenda survives its encounters with Congress unscathed. Barack Obama arrived in the White House in 2009 with big majorities in both houses, and his Affordable Care Act — less ambitious than even Biden’s current plan — barely survived.

In that sense, what Warren has done is useful. She’s tacitly acknowledged that she can’t get everything she wants on Day One, and she needs a backup plan. She doesn’t admit that Medicare for all will be hard to pass — “I’ll fight my heart out at each step,” she promises — but that’s what she means.

It’s a nod toward realism. It’s a step forward in the Democrats’ debate on voters’ top domestic issue.

And it’s an intriguing step forward in the still-brief political career of Elizabeth Warren. She’s no head-in-the-clouds Harvard professor. She’s become a cannier, more practical politician.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.