In this California ‘Trump country’ town, folks hear the impeachment talk, but it feels a world away

TAFT, Calif. — On the road into Taft, fields of fruit trees give way to orchards of oil rigs nodding on golden hills that shimmer against a blue sky like creased velvet.

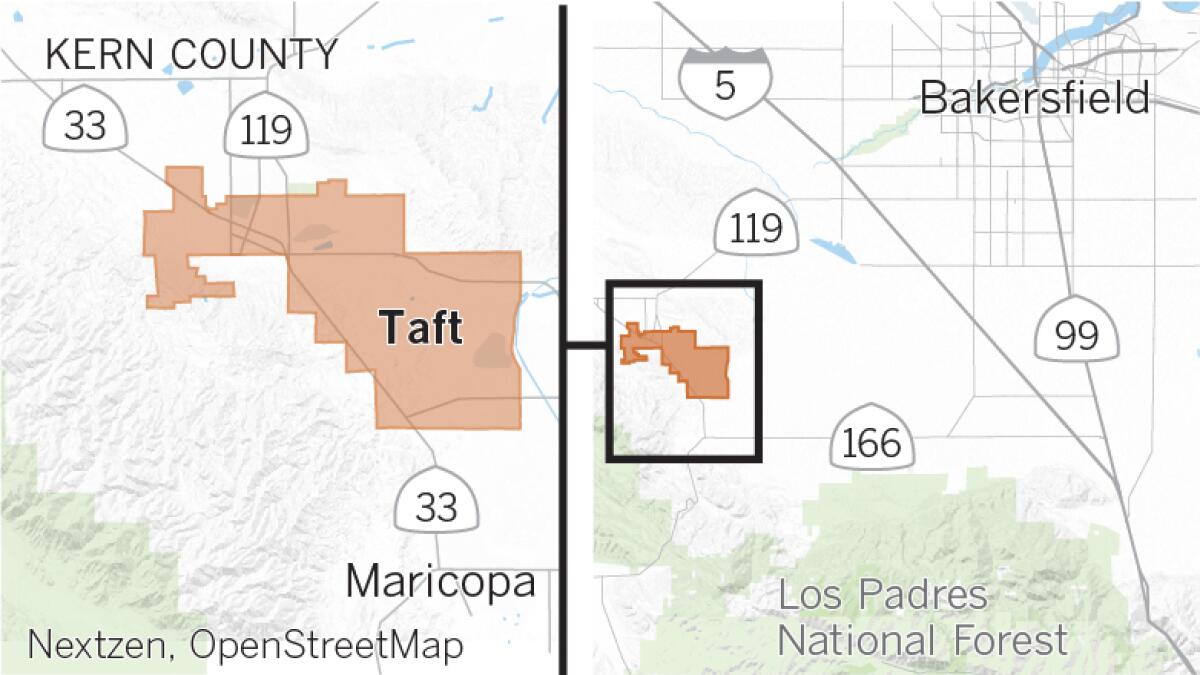

This small oil town two hours northwest of Los Angeles has one stoplight and a city center that seems to go dark well before the sun goes down. Friday night football is the hottest ticket around. Children play on the quiet streets without a parent in sight. Taft, with its 9,400 or so people, feels a world away from the impeachment drama in the nation’s capital.

The city got its name from the 27th president, William H. Taft, who was famous for telling people that “politics makes me sick.” Around here, a lot of people would agree.

Impeachment doesn’t naturally come up in conversations, even as the House inquiry of President Trump heats up and hearings with key witnesses are about to go public.

It’s not that people here don’t like to talk politics; many are just exasperated with the bitterness and division straining the rest of the nation.

Marketing specialist T. Aaron Carter, a voter registered with neither major party who wryly described himself as the most liberal person in this rural outpost on the southwestern edge of the San Joaquin Valley, feels something’s missing.

Senate impeachment trial could keep 2020 candidates in Washington during lead-up to Iowa

“We’ve lost our ability to argue anymore,” he said about much of the country. “It’s either you’re with me or against me.”

Carter, 41, described his hometown as a place set in its ways politically but tolerant, a tight little society that allows people who aren’t alike to disagree and get along, fight but still count on each other.

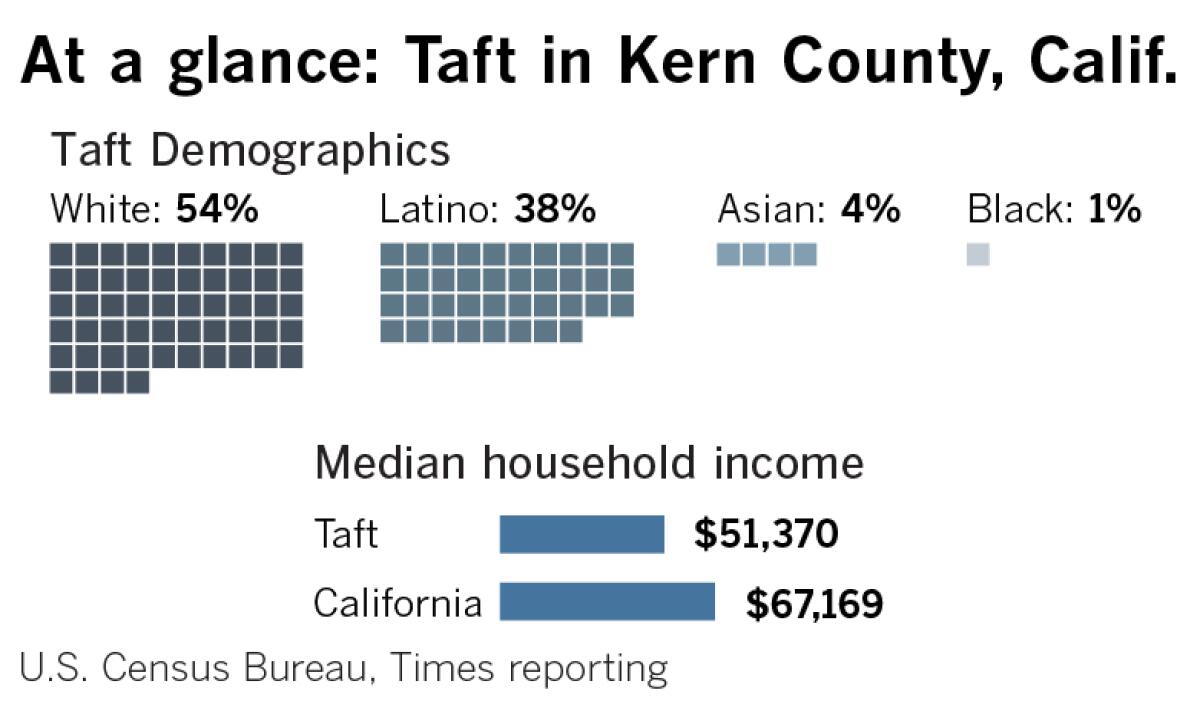

Kern County, where Taft sits, went for Donald Trump in a big way in 2016. The president and fossil fuels are regarded as good things here.

Carter has lived in more progressive parts of Northern California, and is well aware that Taft is a red stronghold in an overwhelmingly blue state.

“Up there, I was defending oil, and down here I’m defending trees,” he said, shaking his head at the political two-step he’s had to perform.

Sitting at a sports bar next to Kasey Morris, who identifies as a libertarian, Carter talked about Taft as a more rugged kind of California that at its best offers up a kinder version of America, where Democrats endure their fair share of ribbing but where anyone can feel at home.

For his part, Morris doesn’t think Taft is perfect but he appreciates its “salt-of-the-earth” decency.

“As much as I disagree with the politics here, I want my kids to go to Taft High School,” said Morris, 40, a single father of two.

“The desert breeds a harder person,” Morris said. “You have to be, especially if you’re going into the oil business. There’s a term called ‘oil field strong.’”

Taft sits atop one of the largest oil reserves in North America, a collection of underground petroleum lakes stretching for dozens of miles west of Bakersfield. Thousands of oil workers known as roustabouts covered the hills and plains with oil rigs to extract the riches, turning this desert outpost into a boomtown.

The Elk Hills oil field here was caught up in one of the most famous federal bribery cases in American history: the Teapot Dome scandal during the Harding administration in the 1920s.

Today the oil industry still employs thousands of people in the valley, making it one of the region’s top job producers.

Trump’s support for oil drilling is one reason Les Clark sees him as an ally of the industry that has put Taft on the map. Clark, an oilman and well-known character in Taft, let his lunch at Black Gold Brewing go cold to share his take on politics.

“You’re in Trump country; it’s not Pelosi country,” said Clark, in a reference to San Francisco’s Nancy Pelosi, the Democratic speaker of the House.

“People ask if we’re better off” with Trump, the wisecracking 76-year-old Republican said. “Yeah, we’re better off. He’s pro-energy.”

By the way, he added, “if people don’t like what he’s doing, there’s an election coming up.”

But Clark didn’t dwell on the impeachment inquiry.

In Taft, he said, the national political machinations take a back seat to daily life and local concerns. A private prison here has been slated for closure, which would put more than 300 area residents out of work. People here want the state and federal governments to safeguard the oil industry.

Clark fretted more about California’s taxes and its tight regulation of the oil industry than the impeachment effort. He’s no fan of Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom and doesn’t hesitate to say so, repeatedly.

The town’s Republican mayor, Dave Noerr, who’s serving his fourth term, recalls telling the late hedge-fund mogul T. Boone Pickens during a visit four years ago that Taft is “the greatest city in the United States.”

As public hearings on impeachment near, many Americans haven’t made up their minds, a USC/Los Angeles Times poll finds. They’re generally younger, less partisan and paying less attention.

Noerr said he half-jokingly told Pickens: “The only problem is we’re surrounded by the state of California.”

Noerr, 60, has cultivated not just a skeptical attitude toward the state and federal governments but a complicated connection to the land — and what comes out of it. While he runs a crane and trucking company that supports the oil and gas industries, he said he worries about how best to protect the environment as intensely as any climate change crusader.

Noerr holds no illusions about the fact that despite the surrounding farms and the private prison at the edge of town, oil is this town’s lifeblood. It fuels the local economy and seeps into almost every aspect of life.

Every five years, thousands descend on Taft for Oildorado, a festival celebrating the community’s love affair with petroleum. The town paper is called the Midway Driller. The paper at Taft Union High School is the Gusher. The biggest landmark downtown is a towering bronze monument that pays tribute to oil workers.

Like the mesmerizing rise and fall of the thousands of steel “horse heads” that drive pump rods deep into the earth, Taft’s fortunes move in sync with the global oil markets, as well as political and economic trends closer to home.

“Anything that affects the oil companies affects every single aspect — it affects our jobs, it affects our schools,” said Pamela Noyes, 45, who was born and raised in Taft and works as a server at Black Gold Brewing Co.

Her father worked in the oil fields and a grandfather worked in agriculture.

“Our men are pretty much one or the other,” she said with a laugh.

Right now in Taft, she said happily, “we all have our jobs and we’re all doing well.” She steered clear of talking politics.

Gazing out over oil pumps dotting the Midway-Sunset oil field south of town, which is run by the energy company Aera, operations manager Jeff Joseph, 55, marveled at the consistency and longevity of oil production here, which is kept moving 24/7 by more than 400 workers.

“This industry has been the American dream for me,” he said, with the steady work allowing him to raise a family.

Taft has a high crime rate, but Mayor Noerr dismisses the statistics, saying the city is “a safe place and a good place” to put down roots.

Racism has been a issue. In 1975, the dozen or so black residents, students at Taft College, were run out of town after tensions flared up over an alleged relationship between a black man and a white woman.

But at its best, Taft also shows a little bit of the openness that distinguishes California.

Hundreds crowded the stands at Taft Union High School’s football field on a recent Friday night to watch the Wildcats try to turn around a lackluster season.

As the game ended in a loss, teens celebrated Sadie Hawkins Day by lining up to dance in the dark to a deejay on the school’s nearby baseball diamond.

Jeb Burke, the cheerleading squad’s only male and its co-captain, climbed into the stands to receive hugs from his mom, dad and siblings.

As a gay high school student in a town with a tiny LGBTQ community, the 17-year-old says he sometimes encounters closed-minded people in Taft, but he’s also come to think of it as a place where “if you’re ever in trouble, you can ask someone.”

“That’s the great thing: We all have each other’s back,” said Burke’s mother, Moneé Burke, 45, who runs a salon in town. “We set it all aside and it’s like, ‘What do you need?’”

Far from itching to leave, her son is planning to stay for at least couple of years to attend Taft College.

Taft may be conservative, “oil field strong” and proudly pro-Trump, but it has made a place for him, too.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.