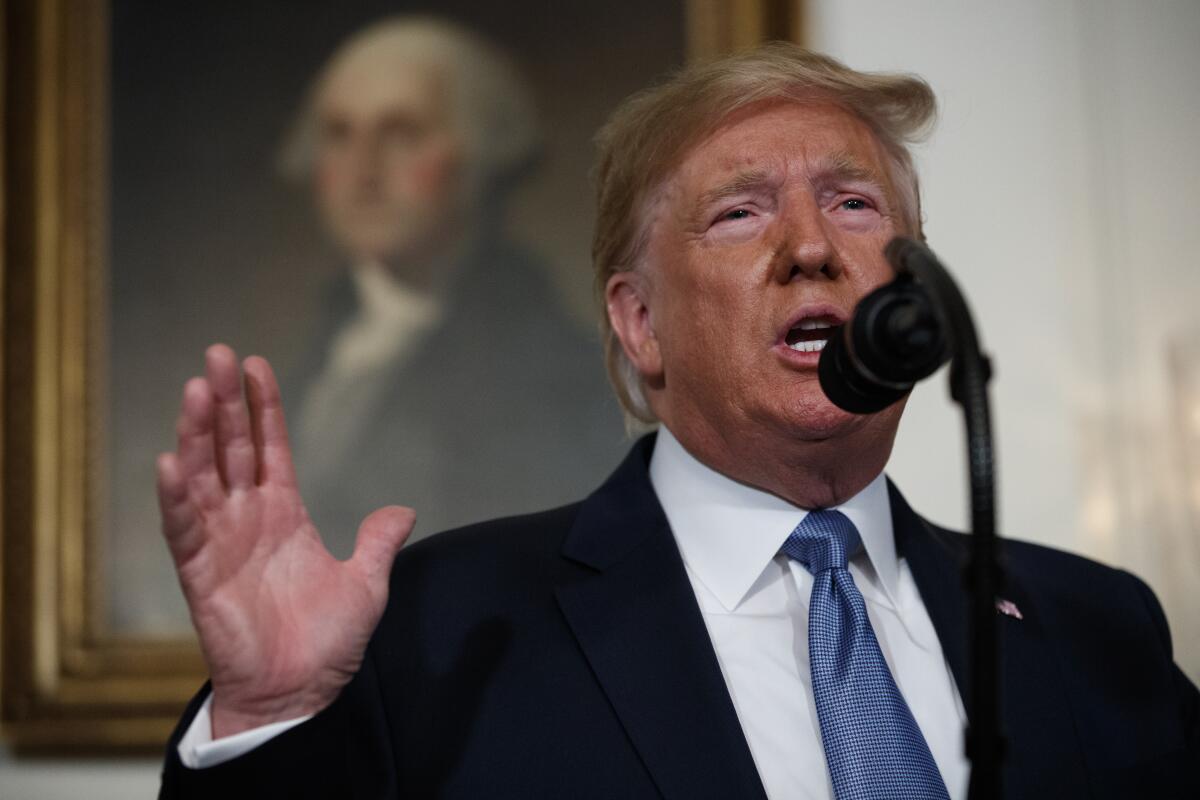

Trump administration begins formal U.S. withdrawal from Paris climate agreement

WASHINGTON — The Trump administration gave official notice Monday that it will pull the United States out of the Paris climate accord, a long anticipated move and a significant step in America’s retreat as an environmental leader.

Despite the president’s repeated claims to have already left the agreement, the U.S. is still very much a part of it. Under the terms of the accord, the formal withdrawal process will take another year to complete, such that the earliest the administration can officially exit the agreement is Nov. 4, 2020 — the day after the next presidential election.

The decision to abandon the agreement makes good on a campaign promise and is in keeping with the president’s belief that climate change is a hoax. It has been widely expected since June 1, 2017, when Trump announced his intention to withdraw, criticizing the accord as “simply the latest example of Washington entering into an agreement that disadvantages the United States to the exclusive benefit of other countries.”

In a statement released Monday, Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo said the president decided to withdraw from the agreement because of the “unfair economic burden” it imposed, but that the U.S. would continue to work with other countries to reduce emissions and “enhance resilience to the impacts of climate change.”

“The U.S. approach incorporates the reality of the global energy mix and uses all energy sources and technologies cleanly and efficiently, including fossils [sic] fuels, nuclear energy, and renewable energy,” Pompeo said.

Democrats in Congress panned the move. New Jersey Sen. Robert Menendez, the top Democrat on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, released a statement calling it “one of the worst examples of President Trump’s willful abdication of U.S. leadership.”

“By charging forth with this withdrawal, the Trump administration has once again thumbed its nose at our allies, turned a blind eye to the facts, and further politicized the world’s greatest environmental challenge,” he said.

The year-long legal process required to leave the agreement means that whether the U.S. ultimately abandons its commitment depends on the outcome of the 2020 presidential election.

How close can U.S. cities, states and companies get to meeting the country’s abandoned climate goals without help from the federal government?

All of the Democratic presidential candidates have promised to rejoin the Paris agreement and some, including many of the leading candidates, have called for the U.S. to set more ambitious emissions reduction goals.

Samantha Gross, an energy and climate expert at the Brookings Institution, said that rejoining the agreement would be far simpler than leaving it because there is no waiting period.

“The accord is really designed to bring people in and keep them,” Gross said. “They need very little notice at all to let us back in.”

If Trump is reelected, his decision to withdraw from the agreement will turn the U.S. into an outlier.

In the years since representatives from 195 nations gathered in France in 2015 to approve the landmark accord, none except the U.S. has threatened to withdraw. And though foreign leaders have tried to persuade the president not to leave, their calls and entreaties have been ignored.

The accord, which took years of international negotiations to reach, differed from previous environmental treaties in that it called upon all countries — rich and poor, developed and developing — to commit to voluntarily lowering their emissions of planet-warming greenhouse gases.

Its central aim was to keep global warming “well below” 2 degrees Celsius this century, potentially forestalling the most devastating effects of climate change. At its most ambitious, the agreement hoped to limit warming to just 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Countries were not legally required to meet particular targets and they were given the flexibility to set their own goals. Under the Obama administration, the U.S. pledged to reduce its carbon emissions by at least 26% below 2005 levels by 2025.

The agreement was meant to be a first step in the fight against climate change. But nearly four years after it was signed, the U.S. is not on track and neither is much of the rest of the world.

A U.N. report released in 2018 found that many large emitters were unlikely or uncertain to fulfill their climate commitments, including China and the U.S., which lead the world in greenhouse gas emissions. According to data from the Climate Action Tracker, the U.S. is only projected to reduce its emissions by about half of its original goal.

Environmentalists say part of the reason the U.S. is falling short is because of the president’s agenda of rolling back regulations intended to reduce carbon emissions.

Since taking office, Trump has replaced the Clean Power Plan, President Obama’s signature domestic program to curb greenhouse gas emissions, with a new plan that does away with aggressive nationwide goals for reducing the energy sector’s carbon footprint. The administration has also announced its intention to weaken vehicle emission and fuel efficiency standards, a move that would result in Americans burning more gasoline and emitting more carbon dioxide than they would have under the current regulations.

Dozens of states and cities across the country responded to the president’s plans to withdraw from the Paris accord by vowing to fulfill the U.S. commitment without Washington’s help. Yet the administration has pushed back against this as well, most recently by announcing plans to revoke a decades-old waiver that California and 13 other states have relied on to follow tougher car emissions standards than those required by the federal government.

The Obama administration’s emissions reduction goals were already modest, Jean Su, energy director with the Center for Biological Diversity’s Climate Law Institute, said in a statement. But the Trump administration’s industry-friendly agenda has undercut them.

“Most Americans know we need urgent action, and they realize this administration’s pro-polluter policies have devastating consequences,” Su said.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.