Column: Hunter Biden — and Trump’s children — follow a long line of White House relatives cashing in

WASHINGTON — The tangled tale of Hunter Biden is worthy of a Russian, or maybe Ukrainian, novel: A ne’er-do-well son goes abroad to seek his fortune, but succeeds only in endangering his father’s presidential campaign.

In 2014, Hunter, a not-very-successful lawyer who had been in and out of alcohol rehabilitation and debt, landed a lucrative job working for a Ukrainian energy mogul.

Big mistake. His father was vice president of the United States. No matter what work Hunter did or didn’t perform, the aroma of influence-peddling was unavoidable. Second mistake: His father didn’t try to talk him out of it.

Hunter’s contract, which paid him $50,000 a month for a period until he decided not to renew it in May, has given President Trump and his personal investigator, Rudolph W. Giuliani, an enticing target — perhaps even a way to knock a leading Democratic candidate out of the 2020 presidential race.

Trump himself asked the president of Ukraine in a telephone call to investigate the two Bidens. The call was the final straw that landed Trump in impeachment proceedings. That was Trump’s mistake.

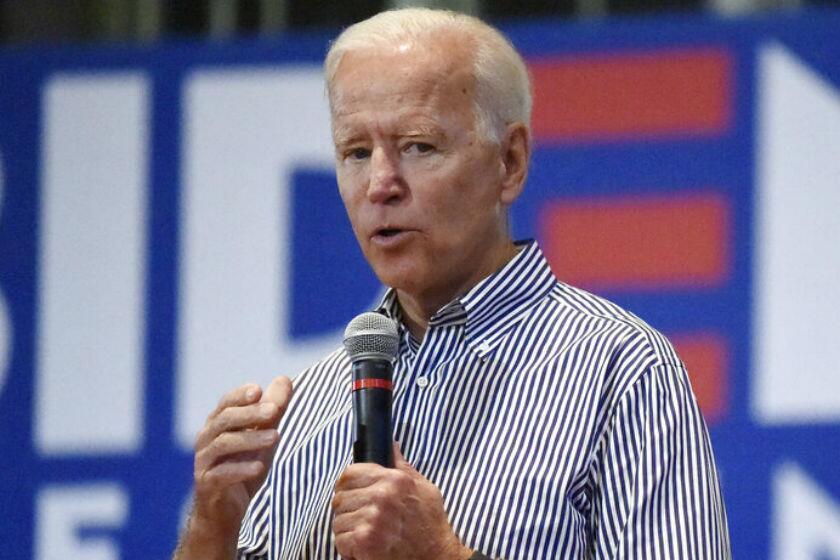

Meanwhile, Joe Biden is trapped between loyalty to his son and the needs of his presidential campaign. He’s not saying anything about the charges except that they’re not true. He wants to keep the focus on Trump, not his son, who’s in Los Angeles trying to rebuild his troubled life.

Hunter told the New Yorker he doesn’t think he did anything wrong, although he’s unhappy about the pain he has caused his father.

“I’m saying, ‘Sorry’ to him, and he says, ‘I’m the one who’s sorry,’ and we have an ongoing debate about who should be more sorry,” Hunter said. “And we both realize that the only true antidote to any of this is winning [the election]. He says, ‘Look, it’s going to go away.’”

And it might. As more evidence about Hunter’s time in Ukraine has trickled out, it has turned up no evidence that either Biden broke the law. Quite the contrary.

The Trump impeachment firestorm hit just as Biden was sagging in the polls.

Trump, Giuliani and their surrogates allege that, as vice president, Joe Biden pushed Ukraine to fire a prosecutor because he was investigating Hunter’s patron. But the evidence available so far shows Trump has the story backward: the U.S. and its European allies wanted the prosecutor replaced because he wasn’t pursuing corruption vigorously enough.

Some readers by now are ready to scream: Why are you talking about Hunter Biden at all? What part of “false equivalence” don’t you understand?

There’s no equivalence. Trump’s allegations against Biden don’t stand up. But the Democrats’ impeachment inquiry against Trump, for pressing Ukraine’s president to investigate Biden during a July 25 phone call, is based in large part on the declassified account of the conversation released by the White House.

Lawmakers still want to know whether that demand was linked to Trump’s decision to withhold $250 million in weapons, communications gear and other military aid to help Ukraine fight a Russian-backed insurgency.

Some Republicans argue that Hunter Biden’s job might be legal but still doesn’t look right — because he appeared to be trading on his connection to his father.

They have a point. Hunter Biden is only the latest in a long line of relatives of elected leaders who appear to have used their names to open doors. In recent decades, Presidents Nixon, Carter, Clinton and George W. Bush all had troublesome family members.

Which brings us to three other children: Donald Trump Jr., Ivanka Trump and Eric Trump.

Donald Jr. and Eric run the Trump Organization, which their father still owns. They have promised to seek no new foreign deals while he is president, but they are still building real estate projects that were announced before his inauguration, and they say they will resume making deals after he leaves office.

Days after launching an impeachment inquiry, House Democrats consider whether they have grounds to charge President Trump with obstruction.

Those self-imposed rules come with loopholes: Donald Jr. has met with wealthy prospective buyers in Indonesia, India and other countries since Trump took office.

Ivanka Trump, officially an advisor to the president, operated her fashion company for a year and a half after entering the White House. She closed it in 2018, saying it had become a distraction.

Meanwhile, she collected dozens of trademark grants in China under applications she filed before her father’s inauguration. In 2017, she received three trademarks on the same day she and her father dined with Chinese President Xi Jinping at Mar-a-Lago.

Anything illegal there? Not at all. But would she have been able to chat up the leader of the world’s second-largest economy if her father wasn’t president? Not a chance.

By calling the president a whistleblower, Stephen Miller took Trumpian doublespeak past the point of absurdity and revealed its duplicitous truth

Just as with Hunter Biden, foreign governments and others see opportunities to curry favor by doing financial favors for a high official’s family.

On Sunday, Treasury Secretary Steven T. Mnuchin explained what he thought was wrong about the Biden case.

“What I do find inappropriate is the fact that Vice President Biden’s son did very significant business dealings in Ukraine,” he said.

Wouldn’t that restriction cover Trump’s children?

Mnuchin fumbled. “I don’t want to get into more of the details,” he said, then insisted that the Trump deals “pre-dated his presidency.”

Nonsense. If Trump’s kids get a pass for cashing in while their dad sits in the Oval Office, Hunter Biden does too.

But let’s give Mnuchin credit for proposing, if only inadvertently, a very sensible “Mnuchin Rule”: relatives of the president and vice president should not engage in “significant business dealings” abroad. Sorry, kids. That means you too, Ivanka, Eric and Donald Jr.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.