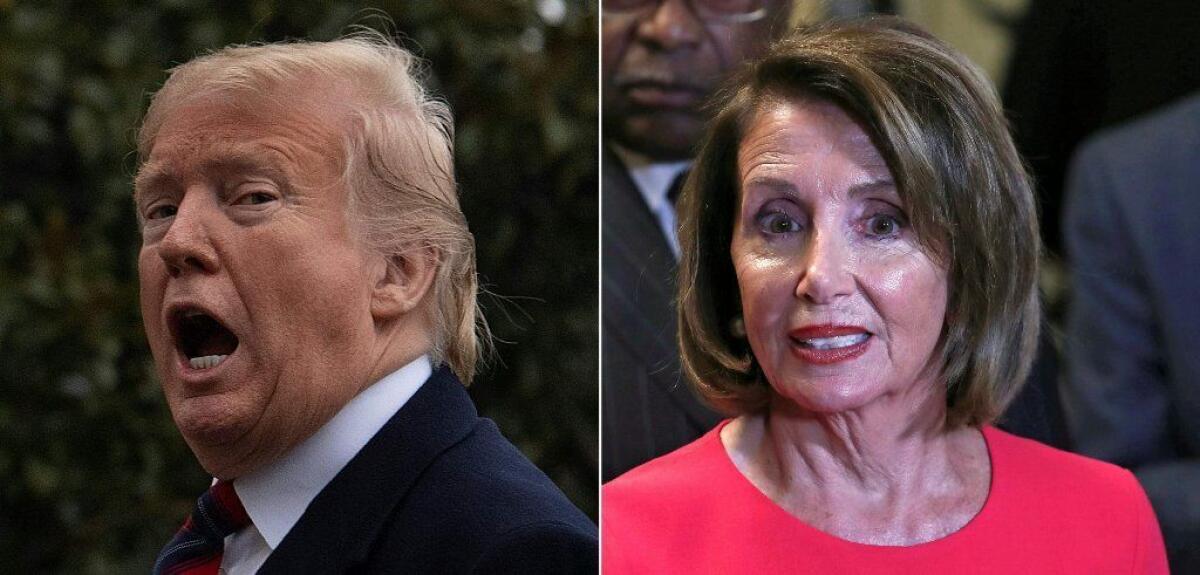

Why Nancy Pelosi is confident as she confronts Trump on impeachment inquiry

WASHINGTON — Speaker Nancy Pelosi and President Donald Trump have been at odds virtually since he took office.

They squared off in the Oval Office over shutting down the government. She insulted his “manhood” and he dubbed her “Nervous Nancy.” He’s trashed her home of San Francisco and she dismissed him as unworthy of his office.

But their political rivalry — which at times included kitschy tweets and sarcastic memes that did little more than rile up both parties’ bases — has spiraled into one of the gravest questions Congress can consider : impeachment of the president.

Pelosi begins what is expected to be a short sprint toward an impeachment vote — perhaps no longer than two or three months — with confidence. She already has the support of the vast majority of her Democratic members and believes the American public will agree, particularly as the facts are laid out.

But just as important, because the president’s interactions with the Ukrainian president have brought the debate into the national security arena, Pelosi sees the upcoming fight as one she can wage on familiar turf thanks to her 25 years of experience on the House Intelligence Committee.

When Trump called Pelosi on the phone on Tuesday to discuss gun legislation and Congress’ demand for access to a whistleblower’s complaint about his alleged abuse of power, the speaker was blunt: “Mr President,” she said, “you have come into my wheelhouse,” according to a person familiar with the call.

The House of Representatives intends to vote to impeach President Trump for abusing his office and obstructing Congress, a condemnation that only two other U.S. presidents have faced in the nation’s 243-year history. Despite the historic nature of the vote on charging the president with committing high crimes and misdemeanors, Trump’s fate has been sealed for days, if not weeks in the Democratic-controlled House.

Trump has acknowledged pressing the Ukrainian president to investigate former Vice President Joe Biden — a possible 2020 presidential rival — even as he withheld nearly $400 million in U.S. aid to that country.

Pelosi’s familiarity with such sensitive matters of national security — along with the seriousness of the allegations — are what helped push her to feel comfortable enough to end her long-standing resistance to an impeachment inquiry.

Democrats are betting that because Trump’s actions potentially threatened the fairness of an upcoming election, the new allegations are more timely and more likely to resonate with voters, who didn’t understand or follow many of the details of the Mueller report into Russian election interference.

“It’s extremely important when we’re dealing with this lane, which is so connected to the heart of the role of the Intelligence Committee, that [Pelosi] has background in this,” said Rep. Elissa Slotkin (D-Mich.), who was an assistant to the first director of national intelligence when he appeared before the panel while Pelosi was a member. “It most definitely helps her frame the process going forward — strategic, clear and efficient — because she has that intelligence background.”

President Trump didn’t see it coming. And his aides have no plan. That’s the situation at the White House three days after Democrats launched an impeachment inquiry.

Pelosi already has a stellar legacy among Democrats, who praise the first female speaker of the House for her handling of the Affordable Care Act, the Recovery Act and the Dodd-Frank Wall Street reform in 2010. She said she planned to retire after the 2016 election, if Hillary Clinton defeated Trump. But at the sunset of her legislative career, Pelosi’s raison d’etre now is leading the Democrats’ charge to hold the president to account. “As long as [Trump’s] here, I’m here,” she told CNN shortly before the 2018 midterms.

“She senses that this is a moment of history,” said Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Fremont). “Her life has been preparation for the moment, and we need to meet that moment.”

Her handling of this process — both the inquiry and a potential vote on articles of impeachment — will be a capstone to her legacy, and one that can only be finally judged with the outcome of the 2020 election.

Whether or not the House impeaches Trump, since conviction in the GOP-led Senate is doubtful, the success of Pelosi’s effort will largely depend on whether he wins reelection — and whether her new Democratic majority retains control of the House.

Reacting to the impeachment inquiry, the president launches a tweetstorm against the California lawmaker, who is leading the congressional investigation.

In 1998, Republicans were so confident about impeaching President Clinton, they campaigned on the issue. But they ended up losing House seats in the midterm election, costing then-speaker Newt Gingrich his job.

In recent days, Pelosi has tried to frame the question through a historical, apolitical lens. She is sprinkling her speech with quotes from Ben Franklin and Abraham Lincoln. And she has repeatedly cited her frequent prayers for the president, his family and their safety.

“Believe me, I am very prayerful about this,” she said Thursday. “This is a heavy decision to go down this path. For some people, it was easier. They saw the transgressions as self evident. I thought we needed more facts to show the American people as to why this was necessary.”

For now, Democrats are almost universally united in their support for an impeachment inquiry. Only a handful of members are publicly opposed to it.

Here’s a look at some of the events that led up to House Democrats’ impeachment inquiry and what has happened since the formal announcement.

“She has something that most people thought would never happen. She has a caucus that’s united on this issue,” said Rep. Dan Kildee (D-Mich.), who helps Pelosi count votes as a member of her whip team.

But centrists say those numbers are soft and stressed that support for an impeachment inquiry should not be construed as support for articles of impeachment. In fact, several centrist Democrats admit privately that they felt they got forced into supporting impeachment by the sudden tide of Democratic support, triggered by the whistleblower’s disclosures.

Those divisions exist under the surface now. But they threaten to spill into the public if Pelosi can’t bridge the divide. Her most immediate questions will be how quickly the impeachment process will move and how the messaging will be crafted.

Pelosi has said the timing would be guided by the investigation in the House Intelligence Committee. That work would eventually be forwarded to the House Judiciary Committee and then to the House floor.

The whistleblower complaint about President Trump’s contacts with Ukraine that set off an impeachment inquiry is released.

Democratic sources suggest that process could be wrapped up by early December. Progressives are eager to move quickly in hopes of keeping calendar year 2020 clear for the presidential candidate to make his or her own case against Trump, free from the impeachment battle.

“I think it’s everybody’s intention here to get this done in 2019,” said Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-Md.), a member of the Judiciary Committee. “We want it to move quickly and the storyline is perfectly clear: the president of the United States went abroad to a foreign government to try to extract information damaging to a political opponent and he was willing to overthrow the rule of the law of the United States to do that.”

But moderates are reluctant to look as though they are rushing toward a predetermined conclusion and are nervous that members in more progressive districts will focus their case on animosity toward Trump rather than the new allegations.

“We have all kinds of members of Congress who are pushing all kinds of different messages,” said Slotkin, who represents a district where Republicans outnumber Democrats. “The most certain thing I can do ... is keep it focused and tight. Talk about what we know the president has acknowledged and said and [Trump lawyer Rudy] Giuliani acknowledged and said. Don’t try to kitchen sink the situation.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.