This voter has vowed to see every single presidential candidate — in person

BEDFORD, N.H. — Cheri Schmitt keeps her to-do list of more than 20 names on a dry-erase board on the refrigerator in her Bedford, N.H., home. Joe Biden. Kamala Harris. Elizabeth Warren. Bernie Sanders.

Schmitt, 56, is an elementary school teacher, and the number of Democrats running for president this year is larger than the average size of her classes. But she’s decided to see every single candidate — in person.

Like many New Hampshire residents, the Democrat is an eager participant in the state’s influential primary election. After Iowa’s caucuses in February, New Hampshire holds the first primary vote, which means candidates have campaigned here relentlessly, in town halls and sometimes living rooms, courting undecided voters like Schmitt.

Schmitt, who is restlessly inquisitive, loves seeing the candidates up close, watching their campaigns evolve as they graduate from awkwardly shaking hands in diners to running stadium-filling victory machines. And she views her job as helping the candidates become more perfect versions of themselves.

Which is how Cheri and her husband, Karl, a quiet, 66-year-old retired civil servant, ended up in the coastal city of Portsmouth on a Friday night this spring, an hour’s drive from home, in a bar whose brick walls were plastered with campaign signs that said “MATH.” The Schmitts and more than 100 others had shown up to hear a tech entrepreneur named Andrew Yang explain why he should be the most powerful person in the world.

Every candidate means every candidate.

“We’ll have to find out what the ‘MATH’ signs are for,” Cheri told Karl, as some older voters milled around with beers and several younger ones looked at their phones.

While waiting, Cheri and Karl chatted with Steven Borne, 55, about their quest to see the candidates. “My 15-year-old is doing the same thing,” said Borne, who then called out across the bar. “Sam! They’re doing the same thing also!” Sam and Steven were planning to see Democratic candidate and former Maryland Rep. John Delaney the next morning, at “the pancake thing.”

This is life in New Hampshire in this wide-open Democratic presidential contest: There’s always a breakfast thing, a brewery thing, a community center thing, another senator or governor who’s showed up in somebody’s backyard down the street with a small entourage and something to say.

When Yang arrived, he was wearing a “MATH” hat and an American flag scarf, and he made his pitch with the self-deprecating deadpan of a stand-up comedian: “The opposite of Donald Trump is what we need, and the opposite of Donald Trump is an Asian man who likes math!” As she often does with candidates, Cheri positioned herself up front and started shooting video with her cellphone, which she’d share with friends later.

Yang revealed what “MATH” stood for: “Make America think harder!”

The crowd laughed. “Definitely much funnier than I anticipated,” Cheri said afterward. But had Yang won Cheri and Karl’s votes that night? “Absolutely not,” she said later.

Yang was the first of six candidates they would go see over four days. More than two dozen Democrats had entered the race since the Schmitts made their see-everyone pact.

But Yang’s platform, which centers on fears of automation taking workers’ jobs, stuck with Cheri. As Karl pulled their SUV out of the garage, Cheri noticed a ticket-taking machine at the exit — doing a job humans used to do. “Automation, right there,” Cheri said. The outsider candidate’s message had sunk in.

::

The next stop was a house party for Beto O’Rourke in Cheri’s bucolic hometown of Bedford the next morning. It’s polite to bring refreshments to help lighten the load for the host family, so Cheri Schmitt brought Arizona Sweet Tea to the Georgian-Colonial-style house where she would see the former Texas congressman in person for the third time.

Cheri piled into a stuffy, high-ceilinged living room with more than 60 other Democrats. Someone had opened the patio doors to let in some cool air. Sign-ups for the event had reached capacity after two hours, which Cheri attributed to enthusiasm among Democrats this cycle.

She likes arriving early so she can chat up the other attendees. (“What the other people are thinking is just as interesting,” she said.) Karl, a little less intrigued by the candidates but more interested in watching the crowd, often hangs back at the events; today he was in the kitchen.

Then O’Rourke materialized in the doorway to the kitchen: tall, tan, his recently graying hair a little shaggy, in a white collared shirt with sleeves rolled to the elbows.

But there was a problem. C-SPAN had come to cover the house party, and the cameraman was standing at O’Rourke’s back, in the kitchen. Someone in the crowd suggested O’Rourke move to the opposite side of the living room to face the camera.

Groans spread through the crowd. Everyone had already settled into a comfortable position. O’Rourke froze, uncertainty crossing his face as he grasped a microphone: “We’ve got our backs to the cameras — yeah — well —”

And in that moment, who was more powerful a force? The more than 60 New Hampshire voters in front of O’Rourke, or the national audience of C-SPAN at his back?

A shorter woman in the audience — who had taken off her shoes to stand on a white alligator-skin chair in order to see O’Rourke better — said to herself, irritation in her voice, “Are you here for the people, or the cameras?”

O’Rourke stayed put. New Hampshire it was.

Cheri, standing in front of O’Rourke, recorded his stump speech, which she later posted to Facebook, then switched to taking notes about O’Rourke’s answers to voters’ questions, which she also shared. “I’m like my own little roving reporter,” she said.

“We don’t normally go to six events in a weekend,” Cheri said in the car afterward; two might be more normal. Karl was driving them past a series of hamlets to their next event that Sunday afternoon in the small town of Warner.

Cheri sees the presence of the candidates in New Hampshire as a luxury — a privilege she knows other voters don’t have. She’s already seen several of the candidates multiple times — even meeting some of their family members — making her an expert on the nuances of their candidacies.

For instance, O’Rourke tailored some of his stump speech to shout out area Democrats and local issues plaguing New Hampshire, while Yang had kept his stump generic. “That’s the difference between someone working in the system” and outside it, Cheri said. Yang also didn’t do a Q-and-A, which she thought was a missed opportunity.

In Warner, more than 60 people were already crammed into the back room of a bookstore to see Kirsten Gillibrand. Staffers strategically placed campaign signs to obscure art depicting nude women on the wall behind where the New York senator would stand.

Cheri left with a good impression of Gillibrand and a lament for the rest of the field. “She was the only female candidate in the state this weekend,” Cheri said. “Go girl power!”

For Cheri, the political is the personal. Her son Connor was 5 when he was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes. She and Karl bought his insulin, managed his injections, bought syringes, took him to get tested, and footed steep bills not fully covered by insurance. The day that Congress passed the Affordable Care Act — with its provision covering preexisting conditions — Cheri sobbed.

“If he doesn’t get insulin, he dies,” she said.

On Sunday evening, she and Karl drove to another neighborhood across Bedford to catch a house party for Sen. Michael Bennet of Colorado.

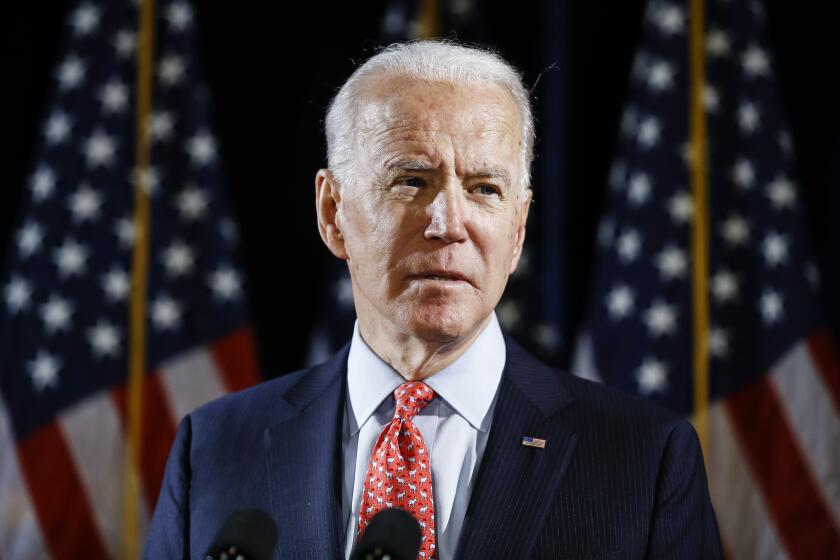

The field is down to Joe Biden now that Bernie Sanders ended his presidential campaign. Here is the Democrat heading for a battle with President Trump.

Bennet, who has thick eyebrows and a curtain of light brown hair sloping across his forehead, stood at a slight stoop as he gave a discursive talk to the crowd in the living room, in long, roaming sentences, about the need to preserve the nation’s institutions.

“I’d like to hear your thoughts on healthcare,” Cheri said to Bennet, telling him about Connor, who is now 24. “In the most wonderful and most powerful country in the world, we have people right here who are using GoFundMe to help pay for their healthcare expenses. What are you going to do about it?”

Cheri’s question brought Bennet’s longest answer of the night — he said America needs “universal healthcare coverage,” but he warned against independent Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders’ plans to effectively replace private employer-provided health insurance with a “Medicare for all” plan.

“It did not seem like a canned stump speech,” Cheri said to Karl afterward. Bennet had talked so fast and so extensively that she had given up on trying to take notes.

::

The next morning, at a gym in Concord, Cheri and Karl sat in the bleachers behind Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey after a campaign staffer invited them. The gym’s overhead lights gleamed on the 6-foot-3 senator’s shaved head. Booker told personal stories about violence in his home city of Newark and about the need for gun control.

Afterward, Karl, typically the more reserved of the two Schmitts, was clearly impressed. “This is the ‘wow’ effect,” he said.

“I want to meet his mom,” Cheri said, maneuvering toward an older woman sitting near Booker as he took selfies with voters. Cheri came back and said, “I thanked her for sharing her son with us.”

A woman who had been sitting in the bleachers in front of Cheri said that before Booker’s event, she thought that Barack Obama was a once-in-a-lifetime candidate and that the nation would never elect another black man as president. “Well, I’ve changed my mind,” she told Cheri.

And this is why candidates grind out event after event after event in New Hampshire. To change the stories about themselves, voter by voter.

That night, Cheri and Karl joined a river of people entering Manchester Community College to catch the race’s headliner, former Vice President Joe Biden. It was the most professionally choreographed and staged event of the weekend. Risers for the television cameras had been erected in the back of the school’s gym; more than 100 attendees were tightly cordoned close to the stage, with a smaller group diverted to a balcony behind the podium, to make the room — and Biden’s support — look and feel fuller. A singer came out and sang the nation anthem.

Then Biden started talking. He was soft-spoken, and sometimes hard to hear; his voice would disappear as he turned away from the microphone and glanced across the crowd. He was the first candidate all weekend to use TelePrompTers, and his head sometimes mechanically pivoted 90 degrees to the left, 90 degrees to the right, 90 degrees to the left, as he warned about the “existential crisis” President Trump had brought to the nation.

Biden left without taking questions.

Standing in the school’s lobby afterward, the Schmitts were mixed on the former vice president. “Joe Biden is the comfortable candidate,” Cheri said. “That cozy old sweatshirt you like to hang out with at the end of the day.” She liked that he has a lot of foreign policy experience.

Karl was worried Biden would turn off younger voters. Biden seemed “low-energy” — and to Karl, he looked, well, old.

“I wouldn’t say he has lower energy,” Cheri responded briskly. “I disagree with that.” She doesn’t see age as a barrier.

“I’d love to be able to meld all the candidates into one big super-candidate. That would be lovely,” she said later. “Unfortunately, I don’t think it’s going to work out that way.”

::

Last week, Cheri Schmitt, getting close to fulfilling her mission to see every candidate running for president, decided to go to a Trump rally in Manchester. (He was not her first Republican candidate; she had previously attended a house party for the president’s little-known primary challenger, former Massachusetts Gov. William Weld.)

Cheri wore a blue hat that said “Life is good,” which stuck out in the sea of red “Make America great again” hats around her, and she warily eyed the conspiracy theorists in “QAnon” T-shirts. To her, the inside of the arena felt like a professional wrestling event where the president was the star performer, delighting in the crowd’s reactions. Cheri didn’t enjoy the show and its open contempt for liberals.

“Politics is not theater to me,” Cheri wrote in a text message later. “It’s about people’s lives, and it was disturbing to see it play out so cavalierly.”

After a while, she couldn’t stomach any more and left early, hoping to avoid the rush to the exits at the end. She was looking forward to reading a fact-check from CNN at home afterward. Schmitt was still undecided on candidates, but it’s safe to say she won’t be voting for the president.

But there was a bonus on the way out: She spotted a strange, bedraggled man in a gray beard wearing a boot on his head. It was performance artist and perennial nonserious presidential candidate Vermin Supreme, whom Cheri knew as a New Hampshire staple.

Schmitt decided to get a grinning selfie with him, and she added his name to the list on her fridge when she got home. A candidate is a candidate.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.