In suburban Texas, ‘it feels like there’s no place for lifelong Republicans like me’

COLLEYVILLE, Texas — Vanessa Steinkamp is the kind of voter that Texas Republicans counted on. She’s a devoted conservative who volunteered for Bob Dole’s presidential campaign, interned for former GOP Sen. Bill Frist and lives in an affluent suburb between Fort Worth and Dallas that is the reddest pocket of a reliably Republican district.

These days, though, Steinkamp feels alienated, not energized, by her party. The thought of voting in 2020 brings on a weary sigh.

“It feels like there’s no place for lifelong Republicans like me,” she said.

Her unease underscores a larger problem for Texas Republicans: Female suburban voters like Steinkamp are no longer a sure bet for the party, injecting new competitiveness into the Lone Star State’s politics.

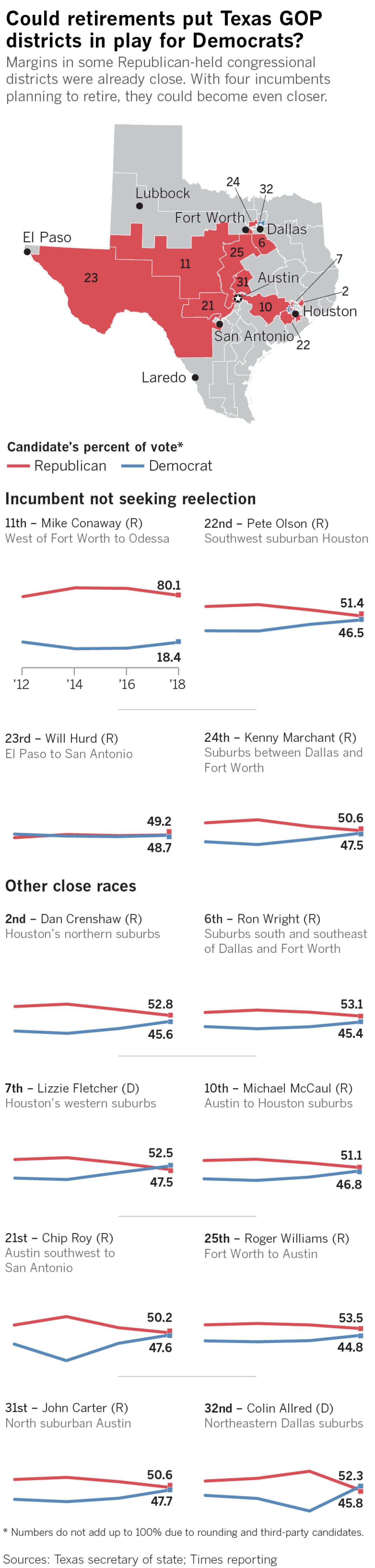

That dynamic captured the national spotlight last week when U.S. Rep. Kenny Marchant, a Republican who represents the communities outside Dallas and Fort Worth, including Steinkamp’s home of Colleyville, said he would not seek reelection next year — the fourth Texas Republican congressman to announce plans to retire.

Across the nation, Republicans are increasingly worried about their strength in once-friendly suburban terrain. Last week, Democrats officially took the lead in voter registrations in California’s Orange County, the storied GOP stronghold. Suburban districts in red states such as Georgia and North Carolina have become hotly contested.

Democrats have pined over Texas for decades, tantalized by the diversifying population and liberal lean of the state’s urban cores. But those hopes had largely been dashed by low voter turnout, a conservative streak among older Latinos, and Republican strength in the rural and suburban areas.

Recent elections, however, have signaled a shift. Donald Trump won the state in 2016 by 9 percentage points — the narrowest margin for a Republican presidential candidate in 20 years. In 2018, voter turnout surged by double digits, and Democrat Beto O’Rourke got within 3 percentage points of unseating incumbent Republican Sen. Ted Cruz.

The news was equally grim for Republicans farther down-ballot. Marchant, who won his first congressional race in 2004 by more than 30 percentage points, eked out a 3-point win last year. Rep. Pete Olson, whose suburban Houston district was once represented by GOP icon Tom DeLay, beat his Democratic challenger by less than 5 percentage points. Olson announced in July he would not seek reelection.

Joe Biden lost Iowa badly when he ran for president in 2008. He’s working hard to make sure it doesn’t happen again in 2020 — and having been Obama’s vice president helps a lot.

The retirements reflect the uphill battle Republicans face in winning back the U.S. House, said Emily Farris, professor of political science at Texas Christian University in Fort Worth.

“It’s not that fun to have to go home every two years, raise a lot of money and have a very close election to be then in the minority,” Farris said.

The suburbs have become increasingly purple thanks to an influx of new residents. Some are coming from the state’s big cities in search of larger, more affordable houses and better school districts. Others are coming from out of state, and around the world, as the healthy economy attracts more workers.

Republican woes have been compounded by a flagging performance among white women in suburban areas. GOP operatives around Dallas-Fort Worth acknowledge this constituency was a glaring weakness in 2018.

Jill Tate, a Colleyville resident who is active in Republican Party groups, said she consistently heard other suburban women express qualms about the GOP over healthcare and immigration.

“They saw the kiddo being separated from their mom at the border, and it’s sad,” said Tate, 45. “We had a lot of [women] voting with their heart.”

Looming over specific policy critiques is a widely-felt exasperation among suburban women over the rancorous political environment — and the blame is falling largely on President Trump and his party.

Steinkamp is among those who despair over Trump’s behavior, which she said falls short of statesmanlike.

“I just wish he would talk about policy and he wouldn’t tweet all the time,” she said as she ferried her three children to the dentist for back-to-school checkups. “He tweets every thought that goes through his mind. I can’t stand that.”

Steinkamp, 42, and her family moved to Colleyville four years ago for her husband’s financial services job. Once predominantly pasture, the town boasts well-manicured subdivisions of big houses sitting on even bigger lots. The median income is $165,000.

Speaking in her spacious brick home at the end of a leafy cul de sac, Steinkamp fretted about how she saw Trump’s vitriolic approach to politics spilling into her community. When she ran for city council this year, her opponent branded her as a liberal interloper from Chicago. The sting of her defeat is still raw.

Her objections extend to Trump’s policies as well. Steinkamp, a government teacher at Tarrant Community College, credited the president with signing bipartisan criminal justice reform legislation, but blanched at him pursuing an $8-billion arms deal with Saudi Arabia over the objections of Congress and toying with granting clemency to imprisoned former Illinois Gov. Rod Blagojevich.

“Now, will I vote for a Democrat over Trump?” Steinkamp said. She thought of the leading progressives seeking the Democratic nomination: Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren and Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders. “I do not agree with almost anything Warren says, what Sanders says. So it’s hard.”

Steinkamp said she might consider a write-in vote.

Women of both parties said Trump’s tweets are leading to a more toxic environment. That polarization was particularly stark after the shooting at an El Paso Walmart on Aug. 3 that left 22 people dead. The suspect, who drove 10 hours from an upscale Dallas suburb, later told police he was targeting Mexicans.

Anjelita Cadena, chair of the Denton County Democratic Party, said the shooting was an outcome of Trump’s rhetoric that she considered dehumanizing to Latinos, and faulted Republicans for not reining in the president.

“If it were my [party], I’d be screaming and yelling, ‘Can you get him to shut up?’” Cadena said. “So, yeah, take away his phone, somebody put a babysitter on him or whatever. But they’re not doing that.”

After shootings in El Paso and in Dayton, Ohio, that killed 31 people, President Trump visited the grieving cities and attacked his political opponents.

Jayne Howell, chair of the Republican Party in Denton County, acknowledges that Trump’s Twitter style jarred her early in his presidency, although she said she ultimately accepted it because “he’s from New York and that’s just how they talk.”

Howell said her pitch to win back suburban women is simple: “Look at the results.”

She rattled off a list of achievements: “Low unemployment. More jobs. ... We’re keeping more of what we make by lower taxes.”

But Trump’s bombast poses a peril.

“Trump is delivering a strong economy, but the messenger is so flawed and angry that people are overlooking the good things that are happening,” said Nancy Bocskor, director of the Center for Women in Politics & Public Policy at Texas Woman’s University in Denton.

Texas Republicans seem to be taking the 2018 warning signs seriously. In the state Capitol — where Democrats won two state Senate and a dozen House seats — legislators shelved highly restrictive abortion bills championed by Republicans in other states such as Alabama and Georgia. Instead, they tried to appeal to women by passing measures to end the backlog in testing rape kits and criminalizing groping.

Few people in Texas are anticipating an overwhelming blue wave in the 2020 presidential election. Jim Henson, director of the Texas Politics Project at the University of Texas in Austin, said Trump’s approval ratings from suburban women has fluctuated between the high 30s and low 40s, a fairly consistent band of support.

“The bottom’s not falling out,” he said.

Henson said there was no doubt Texas was becoming more competitive, but “the speed of change is going to depend on what turnout looks like.”

“It’s a hard call,” Henson said. “The turnout in 2018 increased so much. If you assume Democrats can achieve that level of increase in turnout, well sure, they’re going to be pretty successful. That’s a difficult assumption to make.”

Danee Mastagni, a Democratic strategist who lives in Colleyville, said she believed Trump would win Texas next year.

“But I don’t think he wins it without spending a lot of money here,” she added. “Which means that it puts a lot of other states in play for Democrats.”

Mastagni said her neighbors in Colleyville and other affluent suburbs may be changing their political views but that does not mean they will become Democrats. She can see, though, some key congressional seats or legislative races flipping blue in a crucial year to determine which party will draw the next set of political districts.

“I still think I’d rather be a Democrat in Texas in 2020 than a Republican,” Mastagni said. “I feel like the Republican situation is a little more precarious and that might just be because I feel like they have a lot more to lose.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.