How Scott Walker won, and Gray Davis lost, their recall elections

Scott Walker made history this week in Wisconsin, becoming the first governor ever to successfully beat back a recall attempt.

That means in the entirety of these United States just two governors have been yanked from office before their terms expired, Lynn Frazier and Gray Davis. Of the two, just one survives: California’s Davis.

(Frazier, recalled in North Dakota in 1921, has been largely forgotten, save when people write stories like this one. He was subsequently elected to the U.S. Senate, where as a pacifist and isolationist, Frazier unsuccessfully sought a constitutional amendment outlawing warfare.)

Davis, now practicing law in Los Angeles, declined an interview request and, when asked this week on MSBNC, refused to say whether Walker deserved ouster.

He was philosophical about his 2003 defeat, saying the referendum, along with the recall and initiative process, are a cherished part of California democracy, which any politician has to live with. “If you don’t like that,” Davis said, “find some other line of work.”

So why did Walker survive, handily, while Davis went down to crushing defeat?

For starters, Tom Barrett was no Arnold Schwarzenegger. The Milwaukee mayor who faced Republican Walker as the Democratic alternative wasn’t even the first choice of organized labor, the driving force behind the Wisconsin recall effort.

It may be hard to remember after the disappointment of his years in Sacramento and the scandal that followed his exit from office, but Schwarzenegger was an incandescent candidate, bringing an intoxicating brew of swagger and celebrity to California’s circus-like recall campaign.

The regular rules of politics did not apply. Schwarzenegger refused to debate his opponents, ducked reporters’ questions — his longest interview was a friendly chat on “Larry King Live” — and staged invitation-only town halls. No matter. Days before the vote, he admitted groping and sexually harassing women, then apologized for his boorish behavior. And that was that.

But there were other less glamorous, more substantive reasons Davis lost.

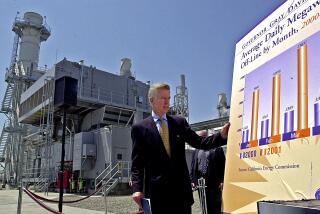

One important difference is that Walker’s election came after a year in office while Davis was beginning his second term. Although Walker could rightly claim he’d barely had a chance to govern, Davis had already accumulated the detritus of four years in Sacramento: controversy over his aggressive fundraising (which now seems quaint, given the relatively meager amount involved), unhappiness over a boost in the state car tax, bruises from perennial budget fights and, not least, the energy debacle that marked his first term.

“All those sorts of things sort of morphed into, ‘We’re sick and tired of the game, tired of the state of affairs here in California’ and Gray Davis became the scapegoat for all of that,” said Paul Maslin, Davis’ political pollster, who also had a front seat on the Walker recall as a Democratic strategist in Madison.

By contrast, Walker could (and did) argue that things were getting better under his watch: The budget was balanced, he held the line on taxes, the state’s business climate was improving. Democrats disputed those points. But despite the polarization surrounding Walker and his efforts to undermine organized labor, there was never the sense — as there was in California — that Wisconsin was headed down the tubes.

As for the two targets, unlike Walker, who became a champion to conservatives nationwide, the diffident Davis was never especially popular with the Democratic base or, for that matter, the voters of California. It is often forgotten that Davis had about a 40% approval rating the day he won reelection in November 2002; it’s not that voter particularly liked the incumbent; he was simply disliked less than his Republican opponent, the hapless Bill Simon.

Walker also benefited from differences in the structure of the Wisconsin recall. The way the law was written, he had a five-month window to raise unlimited sums of money, which he did, tapping that national base of support to raise tens of millions of dollars for his defense. Davis, who’d dismantled his fundraising apparatus after being reelected in 2002, was never able to collect the sums that Walker managed.

The ballot was also structured differently in California. Although Walker ran against Barrett, giving voters an either-or choice, in California the recall was conducted in two parts. First, there was an up-or-down vote on whether to toss Davis from office, then a separate question on who should replace him.

Some Democrats urged Lt. Gov Cruz Bustamante into the race, seeing that as insurance they could hold on to the governor’s office, even if Davis was ousted. Instead, what they ended up doing was undermining the incumbent and clearing the way for Schwarzenegger to romp to Sacramento. (In one of the great, selfless acts of her career, Democratic Sen. Dianne Feinstein, who had long coveted the governor’s office, refused to run on principle; she alone might have been able to defeat the actor-turned-politician.)

“I’ve gone on with my life,” Davis said on MSNBC.

His standing in the history books remains secure. Walker will now be alongside him, doubtless in a much happier place.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.