Capitol Journal: Dam officials should’ve listened to those warnings about Oroville. Now we’re stuck with the tab

Here’s a look at how the Lake Oroville emergency happened. Live updates >>

Reporting from In Sacramento — Climate change did not produce California’s winter flooding that abruptly ended a devastating drought. That weather swing is just how California works.

California has endured rotating cycles of wet and dry periods throughout its history. If there are weeks of deluge, a severe drought is on the way. It happens every decade or so.

But climate change will bring more frequent and robust cycles of extreme weather. Bet on it.

“All of our climate change calculations suggest wetter wets and drier dries,” says Jeffrey Mount, a water expert at the Public Policy Institute of California. He’s also founding director of the Center for Watershed Sciences at UC Davis.

The amount of precipitation will stay basically the same, Mount says. But there’ll be less snow and more warm rain, and thus more rapid runoff into swollen rivers.

The recent soaking, he continues, “is a window into the future. We’re going to have wild swings in weather.”

Former state water director Lester Snow agrees.

“We’ll move very dramatically from historic drought to historic precipitation — a protracted dry period followed by a record storm,” Snow says. “This will increase the need for off-stream and underground water storage.”

“We need to take a comprehensive look into how we operate our dams,” Mount says.

That’s an understatement after the near-catastrophe last weekend at Oroville Dam, the tallest dam in the nation and keystone of the State Water Project. It forms California’s second largest reservoir.

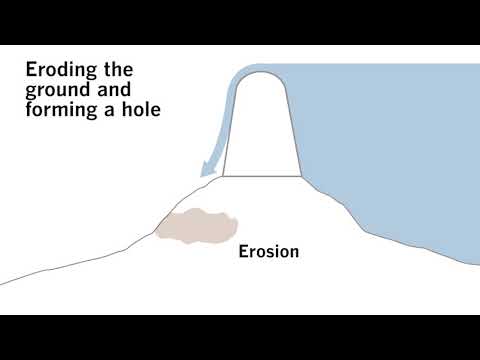

With the lake level rising rapidly and water being released into the Feather River as quickly as possible, a giant crater was carved by erosion in the main spillway. Then water began eroding a nearby emergency spillway that was unlined and had never previously been used.

Was it bad design or bad maintenance? We don’t know. The evidence has been washed away.

— Jeffrey Mount, Public Policy Institute of California

Officials feared a 30-foot wall of water could burst out of the reservoir. So they ordered more than 100,000 people living downriver to flee their homes. Fortunately, no deaths were reported. And two days later the evacuees were allowed back.

Turns out, environmentalists had warned dam officials more than a decade ago that the emergency spillway was vulnerable and should be lined with concrete. It wasn’t. Government officials went into denial mode. Pouring concrete would cost lots of money. No one leaped forward with their checkbooks.

Last weekend, what environmentalists feared could happen did. And it was compounded by the main spillway starting to break apart.

“We need some forensic engineering to find out what happened” on the main spillway, Snow says. “Was something wrong with the concrete? Did something happen underneath? People speculate it might have dried out underneath because of the drought.

“If we can’t rely on the main spillway, we can’t ever fill Oroville again.”

Mount’s take: “It’s an emergency, so it’s finger-pointing time. Someone has to hang for all this. They’re out trying to find someone to hang. They might want to dig up the engineers who designed it and hang them, but they’re dead already.

“Was it bad design or bad maintenance? We don’t know. The evidence has been washed away. The crime scene has been wiped clean.”

Repairs to both spillways could cost $200 million or more.

“Spend whatever money it takes — whether it’s $150 million or $500 million,” Snow says. “Water districts have to pay. That’s my take. It’s the water users’ obligation.”

That means primarily the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California.

There’s bound to be squabbling about whether the repairs are mostly for storing and transferring water or controlling floods. The answer will largely determine whether it’s the water users who pay — such as farmers in the San Joaquin Valley and urbanites in Southern California — or everyone in the state.

I’m with Snow. Charge the water users. A spillway wouldn’t be needed at all without a dam to store water for farms, industry and homes.

But politicians and government would much rather build something new than fix what already exists. Like automobiles, dams need to be periodically serviced to stay operational. But unlike autos, you can’t just trade in a dam on a new one.

There’s another problem with California’s waterworks. They were built for a much smaller population. When Oroville Dam was approved by voters in 1960, fewer than 16 million people lived in California. Now the population is approaching 40 million.

There’s increasing demand for water — not only by people, but corporate growers who keep planting more nut orchards in the parched southern San Joaquin Valley, even during a drought.

Meanwhile, California’s salmon fishery has suffered as the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta is used as an unnatural holding pond for water pumped south, confusing and chomping up young fish trying to reach the ocean.

Agriculture gulps 80% of California’s developed water. At some point — and we’re long past it — California should start zoning for types of crops in the driest parts of the state. We zone for shopping malls, waste dumps and residential neighborhoods. Why not crop types?

There was one ray of sunshine from the Trump administration Tuesday.

White House spokesman Sean Spicer said the Oroville Dam breakdown “is a textbook example of why we need to pursue a major infrastructure package in Congress.”

Gov. Jerry Brown asked President Trump to pitch in with federal aid to deal with the Oroville emergency and flooding throughout California. The governor quickly got a positive reply. No tacky political games.

Now if Trump could just join Brown in fighting climate change.

Follow @LATimesSkelton on Twitter

ALSO

An ‘aggressive, proactive attack’ to prevent disaster at the Oroville Dam

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.