Q&A: You asked, we answered. Here are some of our readers’ questions on California’s proposed single-payer plan

The measure has raised concerns, because it doesn’t specify where money to fund the program would come from. (June 23, 2017) (Sign up for our free video newsletter here http://bit.ly/2n6VKPR)

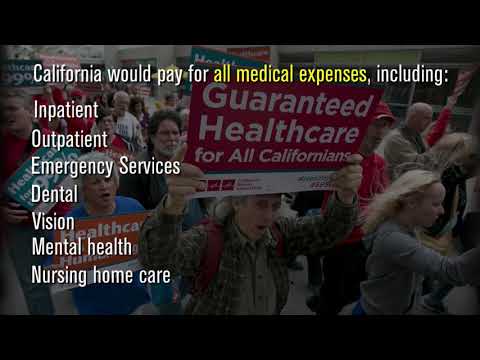

We had some questions about California’s high-profile bill to establish a single-payer system, in which the state would foot the bill for nearly all healthcare costs of its residents. So we looked into the proposal, asking who would be covered, how it would be paid for and other basic questions about how it would work.

Times readers sent us their own questions about about SB 562, the measure by state Sens. Ricardo Lara (D-Bell Gardens) and Toni Atkins (D-San Diego). Many were rooted in their personal experiences. They asked about how this would change their coverage on Medicare, having health issues while traveling or concerns about access to treatment. The variety of the questions underscored that a single-payer proposal like the one being debated in Sacramento is an enormously complex undertaking.

The measure cleared the state Senate earlier this month and now awaits action in the Assembly. To make it to the governor’s desk, it would need significant changes — namely to how to pay for it, since the bill does not currently identify taxes to cover its estimated $330-billion to $400-billion price tag.

Here’s what Times readers wanted to know about the bill:

What would be required to establish California residency and qualify for free medical care?

The bill states that all California residents — those whose primary place of residence is in the state — are eligible, regardless of immigration status. It doesn’t explicitly say how residency would be determined, but proponents of the bill say they envision using the same enrollment criteria as “Health4AllKids,” the program that allows all children younger than 19 — including those in the country illegally — to enroll in Medi-Cal.

Under that program, enrollees need to provide one of the following documents to prove residency: a recent rent receipt, a utility bill, a current driver’s license or state identification card, or evidence of being enrolled in a California school.

“We’re not trying to reinvent the wheel here,” said Michael Lighty, policy director for the California Nurses Assn., which sponsors the bill.

Several readers asked about medical “tourists” — those who could move to California to seek treatment under the new system. Gerald Kominski, a professor of health policy at UCLA, said he could envision such a scenario should the state implement single-payer healthcare.

“There are people all over the country — especially in red states where Medicaid expansion has been denied — who may see this as an opportunity to get the care they need,” Kominski said.

How would this affect my healthcare coverage if I’m out of the state? What if I want to see specialists outside California?

All healthcare expenses incurred by Californians while they’re temporarily out of the state would be covered. So if you break your arm while waterskiing on a family vacation to the Great Lakes, the Healthy California program would pick up the tab.

The bill doesn’t specify what it means by ”temporary,” but Lighty said there would likely be a limit of 60 or 90 days, so that the program wouldn’t be paying for those who have moved out of California.

But what if you want to leave the state for treatment, perhaps to see a renowned specialist for a rare condition? The bill would allow for Californians to have their out-of-state treatment covered if it is “clinically appropriate and necessary” and could not otherwise be provided in state. The bill doesn’t specify, but its sponsors said the program would likely defer to the judgment of doctors if a patient needed to see an out-of-state specialist.

Determining what is “medically necessary” for in-state and out-of-state expenses, is not just a policy matter; it’s a political one. Proponents say the measure would first rely on doctors’ clinical judgment for what treatment is needed. But they also say the system would keep track of physicians who order excessive tests or refer to specialists with higher-than-normal frequency, and would take action to address overuse of care. Exactly how that would be addressed is not detailed in the bill.

That raises the specter of a government board weighing in on appropriate levels of care for patients. Single-payer backers point out that insurance companies already do that by requiring preauthorization or denying certain procedures. But the American public has been known to recoil at even a hint of the government playing the same role. Remember the brouhaha over “death panels” during debate over the Affordable Care Act.

Everybody in, nobody out.

— Michael Lighty, policy director, California Nurses Assn.

Would there be any delay or waiting period for treatment of serious conditions such as cancer?

Most experts agree: More people would likely seek more care under the proposed system, and that could lead to long lines to see a doctor.

In part, that’s due to pent-up demand. Even though California has slashed its percentage of residents without health insurance, there are still 3 million people who are uninsured. A study by University of Massachusetts Amherst economists, commissioned by the nurses union, estimated that 12 million people are underinsured, meaning that they have coverage but high deductibles or large out-of-pocket expenses that inhibit their ability to get the healthcare they need.

There would most likely be increased use of primary care doctors and elective treatment immediately after the universal coverage program went into effect, Kominski said, but may level off once those patients are done playing catch up.

But long delays to treat serious conditions are less likely, he said, because even those without coverage can be treated through “uncompensated care” provided by public hospitals or public clinics.

“I don’t see a sudden increase in demand for cancer treatments. A lot of that care is being provided,” he said. “It’s the more routine care that doesn’t get provided, [such as] management of conditions like diabetes.”

There were similar concerns about the healthcare system being strained when Medicare first started, noted Jonathan Oberlander, professor of social medicine at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. There was even talk of using military hospitals as back-ups to private hospitals when the program went into effect in 1966, as the government braced for an influx of seniors seeking care.

Fear of delays “is an old specter in American healthcare, but it’s probably a phantom,” Oberlander said.

I’m on Medicare — what would this mean for my supplemental coverage? And is this idea of repurposing Medicare money legal?

The single-payer proposal aims to replace Medicare (and Medicaid and other public health programs receiving federal dollars) with the “Healthy California” plan. We heard from lots of Medicare beneficiaries in California wondering how that would actually work.

Most pointed out that they have supplemental insurance policies that are sold by private insurers that help pay for costs not covered by original Medicare; other policies cover additional services.

Under the bill, the Healthy California board would seek to be an authorized provider of Medicare Part B supplemental insurance, which covers medical visits. It also would provide premium assistance for prescription drugs under Medicare Part D, up to the amount that low-income seniors currently receive.

“If the bill as envisioned has more comprehensive coverage than Medicare, naturally you wouldn’t need supplemental coverage as much,” Oberlander said.

Some seniors are enrolled in Medicare Advantage, a private plan that offers more services but narrower networks. Lighty said the plan “does not envision disrupting” those plans and the state would pay HMOs directly. That is not explicitly addressed in the bill.

But is this all possible? Some health policy experts have called the prospect of the federal government granting a waiver a pipe dream — and not just for the political improbability of the Trump administration willingly lending a hand to California’s single-payer experiment.

Micah Weinberg, president of the Bay Area Council Economic Institute, has argued that there would need to be a change in federal law, not just a temporary waiver, for California to dramatically repurpose these federal dollars.

“There’s no process that would allow [the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services] to say, even if it were so inclined, ‘Oh yeah, sure, do away with the Medicare program,’” Weinberg said. “That’s not something you can get a waiver to do. You would have to change federal Medicare law to do that.”

Supporters are adamant that they see a pathway to getting such approval, through a variety of waivers or pilot projects. And the while the waiver process has never been used to establish a single-payer system before, the federal government continues to pay for an “all-payer” system in Maryland, in which all insurers, including Medicare and private plans, pay the same rate for hospital services.

Kominski said the possibility of the federal government approving the program was not out of the question, but it would require some persuasion on California’s part.

“The state has to guarantee that the federal government will not spend more under the waiver program than it would have if it just continued to pay for Medicare the way it does,” he said.

What happens to people who receive insurance through their union? What if they get retiree medical benefits but retired out-of-state?

Union health trusts would no longer administer benefits for their members, but they could still have a role under the new system. The bill says such entities could function as “care coordinators,” which could help members navigate the system and keep track of their records. Other “care coordinators” would include primary care doctors, private health plans or nonprofits approved by the program.

Lighty said entities that offer retiree health benefits would be able to negotiate with Healthy California on a case-by-case basis. Many of the details on that process are not in the bill and would be determined by regulation.

Would California politicians have to go on this single-payer plan?

In a word, yes. All California residents — even the elected ones — would be part of the Healthy California plan. As Lighty said, echoing a favorite chant of single-payer supporters, “it’s everybody in, nobody out.”

ALSO

Robert Pollin: Single-payer healthcare for California is, in fact, very doable

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.