Column: Political Road Map: Voters have placed a lot of California’s budget choices on autopilot

Here’s a simple rule of thumb worth keeping in mind about how California’s budget is crafted: Not all tax dollars are created equal.

Now more than ever, voters have decided that billions of those dollars should make their way through Sacramento with hardly a single politician’s fingerprints on them.

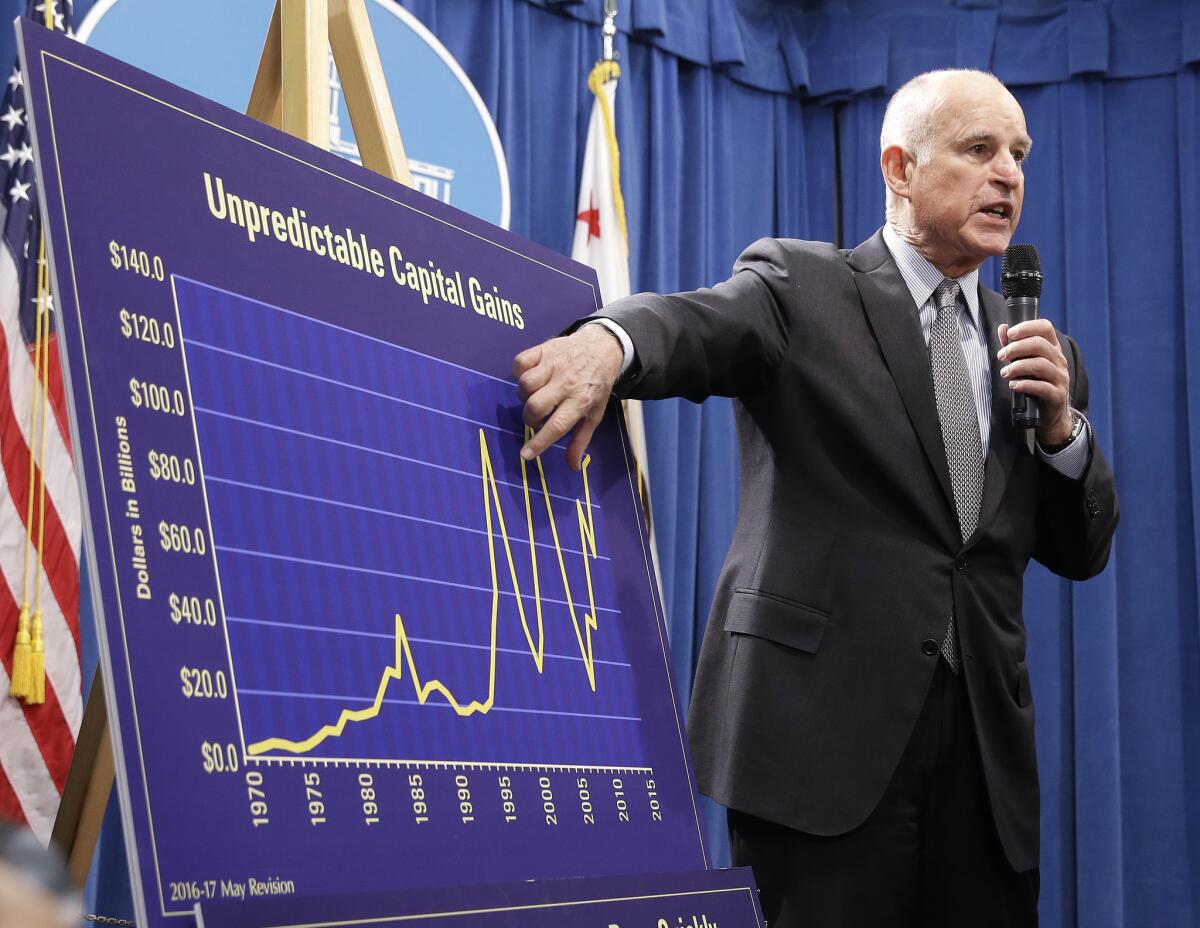

One example came last week, as state senators reviewed Gov. Jerry Brown’s budget plan. Questions were raised at the hearing about why Brown is projecting a $1.6-billion deficit while putting a similar amount of money into the state’s rainy-day reserve fund.

“We could pretty much say that funding the rainy-day fund is our deficit,” said state Sen. John Moorlach (R-Costa Mesa).

Budget staffers then offered up a mini-course in voter mandates, saying that those amounts should be scored on different parts of the ledger.

“It’s just not intuitive anymore,” Legislative Analyst Mac Taylor told lawmakers at Tuesday’s hearing about the rules for revenues. “Your budgetary calculations have gotten a lot more complicated.”

For starters, the rules vary based on the tax revenues in question. Personal income taxes largely go to the all-purpose general fund, accounting for 69 cents of every dollar spent there. But a slice of income taxes paid by millionaires, about $1.9 billion this year, get diverted to a mental health services fund created by voters in 2004. Some of that money will also finance a $2-billion bond to help the homeless.

It’s just not intuitive anymore.

— Legislative Analyst Mac Taylor, telling lawmakers about the confusing rules for spending tax dollars

The remaining income tax revenues are then run through another mandatory filter, one put in place by voters in 2014. Proposition 2 will automatically set aside $2.3 billion this coming fiscal year. That amount is split between rainy-day cash reserves and payments on recession-era government debt.

But as Moorlach and others found out last week, they can’t use that cash to erase the new deficit. Brown would need to declare a fiscal emergency, and his budget team made it pretty clear that a $1.6-billion deficit is more akin to a fire in the wastebasket than a reason to pull the alarm.

Political Road Map: There are more than 15 lobbyists for every lawmaker in Sacramento »

What else flows into the general fund? Corporate tax revenues, for one thing. So, too, do a portion of sales taxes — though they also benefit local governments. Alcohol taxes? General fund. Insurance tax revenues? General fund, in most cases.

Property taxes stay on the local level, though they can also offset some spending of state tax dollars. Gas taxes? There’s not enough time or space to fully explain the labyrinth of swaps and transfers that govern the use of these dollars. Many of the rules were crafted during California’s recession years.

Once all of the various pots of money are split up, lawmakers must honor yet another series of spending mandates. The most consequential of these control the level at which public school funding is set each year. Then there are the rules imposed by voters in November. Proposition 55, which extends current income tax rates on the wealthy, will earmark money for schools and healthcare. Proposition 56, the $2-per-pack of cigarettes boost in the state’s tobacco tax, also earmarks money for healthcare spending.

Once the dust settles, California lawmakers have a smaller role in doling out tax dollars than might otherwise be expected. No doubt some voters applaud anything that clips the wings of politicians, but they shouldn’t get angry when those same elected officials don’t change course on government spending. In many cases, the state’s voters already have their hands on the wheel.

Follow @johnmyers on Twitter, sign up for our daily Essential Politics newsletter and listen to the weekly California Politics Podcast

ALSO

Political Road Map: The rules governing California school finances are, to say the least, confusing

Brown’s budget staff admits an error of almost $1.5 billion

Updates on California politics

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.