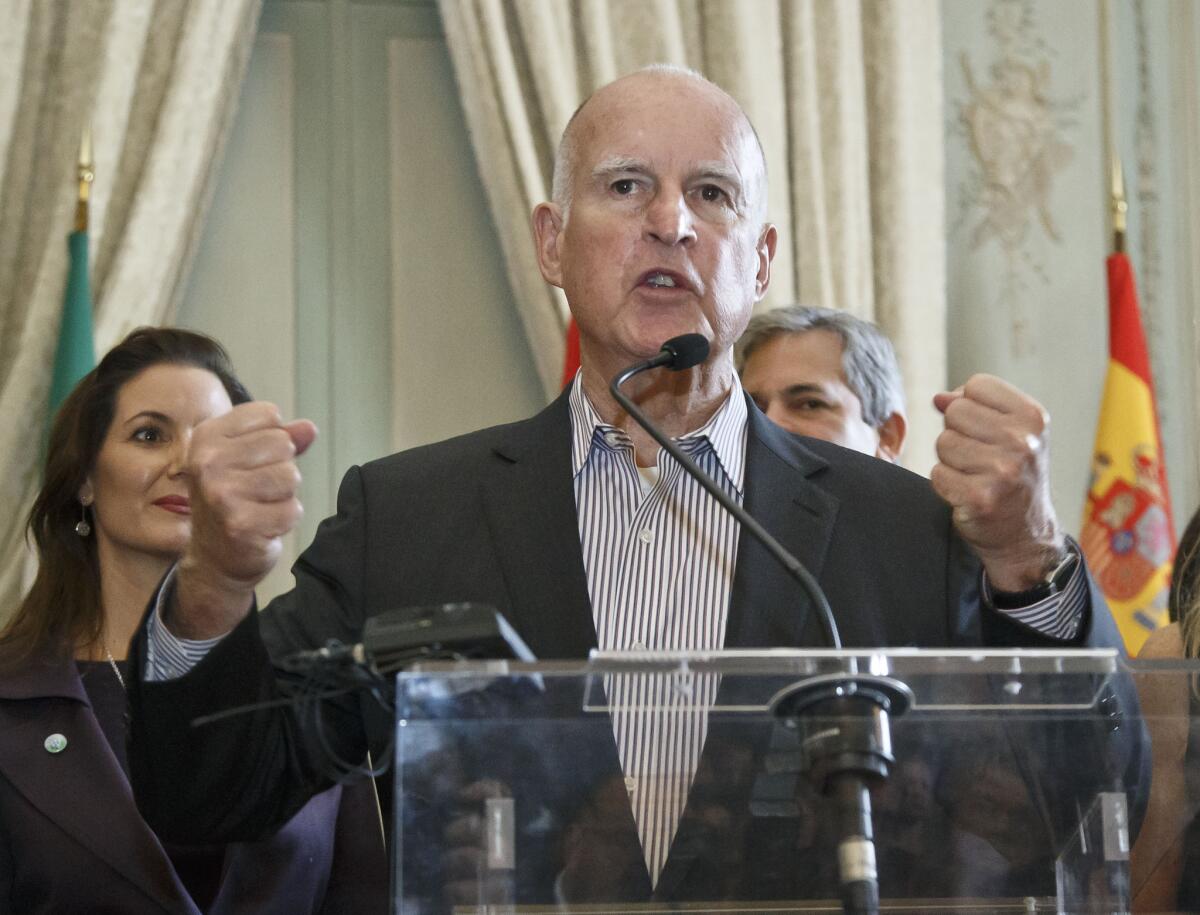

A grand bargain? Gov. Jerry Brown in talks with oil companies about climate change programs

Reporting from Sacramento — Gov. Jerry Brown’s administration has been talking directly with oil companies in hopes of reaching a consensus on extending California’s landmark climate programs, opening a back channel with an industry the governor has harshly criticized as a barrier to addressing global warming.

The dialogue was described by sources who requested anonymity to talk about private discussions and later confirmed by the Western States Petroleum Assn., which represents oil companies in Sacramento.

The organization’s president, Catherine Reheis-Boyd, told the Los Angeles Times that the industry is engaged in “ongoing talks with the administration to improve the state’s current climate change programs.”

The behind-the-scenes conversations come at a time when Brown is searching for the best way to safeguard the cap-and-trade program, which requires companies to purchase permits in order to pollute and serves as the centerpiece of California’s efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The program, an important revenue generator for projects such as the bullet train to connect Los Angeles and San Francisco, has suffered from waning political support and legal questions over how long it can keep operating.

It is far from certain that the conversations, which have been underway for weeks and don’t include lawmakers, will produce any consensus between two sides that have historically been at odds over tackling climate change.

Each camp has reasons to come to the table. Brown wants to avoid having his agenda thwarted by an industry that has proved adept at rallying lawmakers to its defense. Meanwhile, oil companies are seeking an opportunity to influence state policy rather than risk more aggressive efforts from Brown, who has vowed to use regulations to keep reducing California’s dependence on oil — whether or not he gets new legislation.

A key issue in the talks has been the state’s low-carbon fuel standard, which requires the production of cleaner gasoline. Oil companies claim the regulation — which is scheduled to require a 10% reduction in the carbon content of fuels by 2020, up from the current 2% — sets an unobtainable target that will raise costs for consumers.

But state officials estimate the eventual cost increase would be less than 20 cents per gallon, and the Brown administration has defended the regulation as an important tool for curtailing emissions from vehicles, one of California’s biggest hurdles to cleaning up its air.

Even if a deal is reached, the governor would need to sell it to lawmakers with whom he has not always seen eye to eye. Some Democrats are moving forward with their own proposals to extend cuts in greenhouse gas emissions and stem pollution from refineries, setting the stage for a contentious debate over California’s climate policies at the end of the legislative session in August.

Brown would also need to find common ground with fellow Democrats who have been skeptical of cap-and-trade, the bullet train that’s being funded with the program’s revenue and the value of increased environmental regulations.

The governor’s office did not address discussions with the oil industry, but reiterated Brown’s dedication to “solidify and redouble our commitment” to fighting climate change, including an extension of the cap-and-trade program.

“We will work hard to get that done,” said Deborah Hoffman, a spokeswoman for Brown.

The cap-and-trade program was authorized under a 2006 law that set a 2020 target for reducing greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels. Brown wants a new law that would remove any legal uncertainty over whether the system can continue operating past 2020.

A reminder of that uncertainty arrived in May, when a state auction of pollution permits produced far less revenue than expected. The poor results raised questions about the viability of using cap-and-trade money to finance high-speed rail, one of Brown’s priorities.

Direct talks with oil companies might seem counterintuitive for a governor who has denounced the industry for selling a “highly destructive” product. In December, while attending the international climate summit in Paris, Brown said addressing climate change would require radically rethinking humanity’s relationship with oil.

But oil companies have also been formidable opponents in Sacramento — the Western States Petroleum Assn. has spent nearly $13 million on lobbying since the beginning of 2015, according to reports filed with the state. Last year, the industry defeated a proposal to cut oil use for transportation in half by 2030. The measure, SB 350, was pared down to only include increased targets for renewable energy and energy efficiency in buildings.

Now, as the governor faces political challenges to extend California’s climate agenda into the future, administration officials are exploring whether talking directly with oil companies could help clear a path in the Legislature.

The goal is to reach a two-thirds vote in each house, the threshold required to approve taxes and fees. If Brown can accomplish that, he can remove the danger from a lawsuit filed by the California Chamber of Commerce, which has called cap-and-trade an unconstitutional tax because the original 2006 law was only passed with a majority vote. The case is pending before a state appeals court.

A two-thirds vote would require support from at least some Republicans and business-friendly Democrats who have been sympathetic to arguments put forward by oil companies about higher costs to consumers and the need for increased oversight of climate programs.

Reaching the threshold may not be possible without concessions that Brown or environmentalists would consider untenable, such as abandoning or restricting the low-carbon fuel standard. The dialogue between the governor’s office and oil companies has already rattled the alternative fuel industry, and the Coalition for Renewable Natural Gas circulated a message this week warning that the regulation has become a “bargaining chip in statewide policy negotiations.”

Besides the administration’s talks with oil industry representatives, there are other ongoing efforts involving climate change in Sacramento. The Air Resources Board, which has claimed wide legal authority to curtail emissions, is already planning new regulations to keep operating cap-and-trade and other programs past 2020.

In addition, Sen. Fran Pavley (D-Agoura Hills) and Assemblyman Eduardo Garcia (D-Coachella) are pushing a package of legislation to advance California’s environmental policies.

Pavley’s bill, SB 32, would extend and deepen the state’s commitment to reducing emissions, setting a target of 40% below 1990 levels by 2030. Kevin de León (D-Los Angeles) has pledged to throw his weight behind the proposal, telling environmental advocates last week to prepare for a battle at the end of the legislative session in August.

“The ultimate goal is to have these targets written into law,” De León said.

Garcia’s measure, AB 197, would direct the Air Resources Board to create regulations for slashing emissions from “stationary sources” such as refineries, a goal of environmental activists concerned about the impact of pollution on local communities.

The measure also includes proposals that could appeal to more business-friendly members of the Legislature, such as requiring state officials to consider the cost effectiveness of efforts to reduce emissions.

Neither of the bills — which could be approved by a majority vote rather than two-thirds — would explicitly reauthorize the cap-and-trade program, which appears to lack strong political support in the Legislature.

“It’s going to have a tough time,” said Assemblyman Jim Cooper (D-Elk Grove), who said he would like to see revenue from the program more evenly distributed around the state. Cooper is the co-chairman of an informal but powerful caucus of business-friendly Democrats in the Assembly, where climate legislation has faced a tougher audience than in the state Senate.

“We all want clean air,” he said. “I’m not sure if cap-and-trade is the best system to get us there.”

The lack of a unified strategy from Brown and lawmakers to advance California’s climate programs has been frustrating for some environmental advocates.

Alex Jackson, a San Francisco lawyer for the Natural Resources Defense Council, said efforts “continue to be mired in purgatory.”

“There are multiple balls in the air with different timelines and different champions, each doing a different juggling act,” he said. “We’re not primed for a successful outcome.”

[email protected] and [email protected]

Twitter: @chrismegerian and @melmason

ALSO:

California’s cap-and-trade program faces daunting hurdles to avoid collapse

California lawmakers unplug the state’s electric car program

Updates on California politics

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.