Some say California’s bail system is broken. Here’s how two legislators plan to help fix it

California’s bail system is ripe for reform, some say. Police officers and prosecutors point to dangerous or repeat offenders who pay their way out of jail time, bail agents to the high number of people who jump bail and criminal justice advocates to the hefty fees levied on the poor.

This legislative session, as calls for action and legal challenges have spurred momentum for bail reform nationwide, state lawmakers introduced a twin-bill effort to tackle the issue. It would transform how California’s county courts determine which defendants are fit for release while their cases are pending.

But after one of those proposals stalled in the Assembly last week, the future of the other hangs in the balance. Here is what you need to know about that proposal, Senate Bill 10.

Upending the system

Assemblyman Rob Bonta (D-Oakland) and state Sen. Bob Hertzberg (D-Van Nuys) combined forces in December to unveil the California Bail Reform Act of 2017, a pair of identical bills that would eliminate the use of bail fee systems and require counties to establish their own pretrial services agencies.

Under the legislation, those agencies would develop a “risk-assessment tool,” or model analysis to evaluate people booked into jail. Their release would depend on two main factors: What threat do they pose in the community and how likely are they to come back to court?

Bonta and Hertzberg said they wanted to ensure dangerous offenders aren’t able to skip spending time behind bars solely because they can afford bail. Most counties in California require defendants to post a fee up front for their release, and the median state bail rate is about $50,000 — roughly five times higher than the national level.

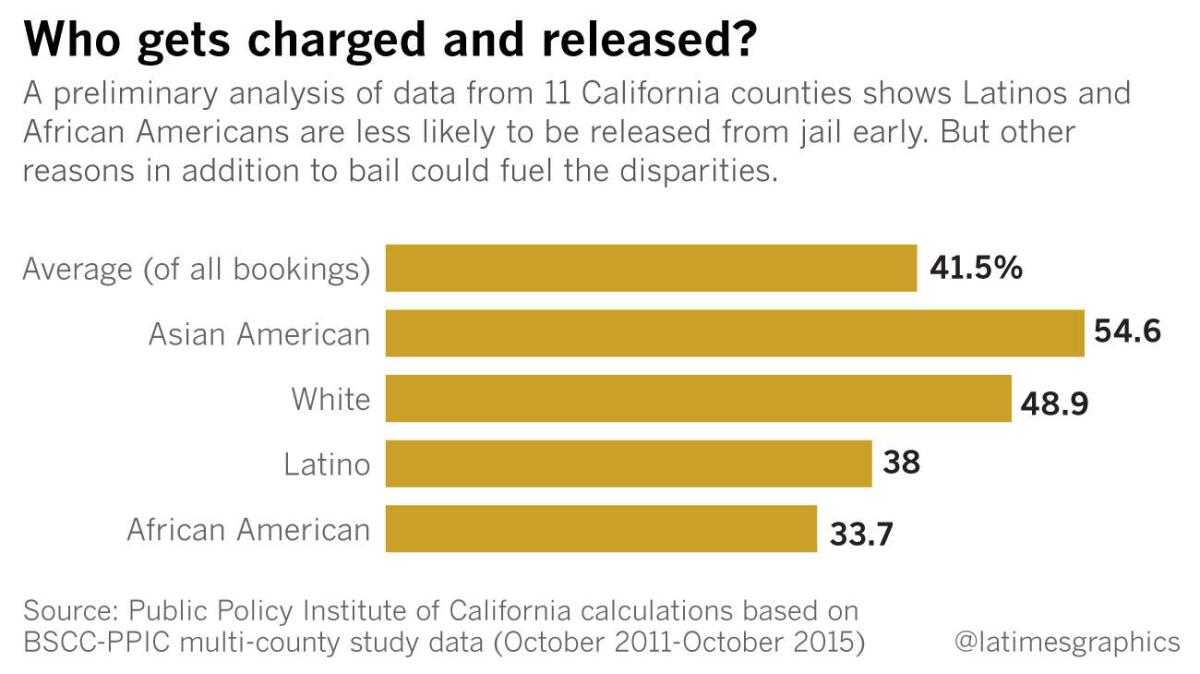

Studies have shown such policies disproportionately affect people of color and the poor. People who don’t have the means to post bail can lose their employment or housing. Even three days in jail can result in loss of wages, jobs and family connections, leaving some defendants 40% more likely to commit a crime in the future, according to pretrial criminal research commissioned by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, a philanthropic organization focused on education, public pension and criminal justice reforms.

What SB 10 would do

- Eliminate the use of fixed money bail fees

- Require counties to establish pretrial services agencies to evaluate defendants for release upon booking based on the public safety risks they pose.

- Only offenders not charged with a violent felony would be eligible for the risk assessment.

- People charged with misdemeanors, except in certain cases such as domestic violence, would be let go without further conditions upon signing a release agreement.

- Agencies would submit their recommendations on felony offenders to judges, who ultimately decide when to release people from jail.

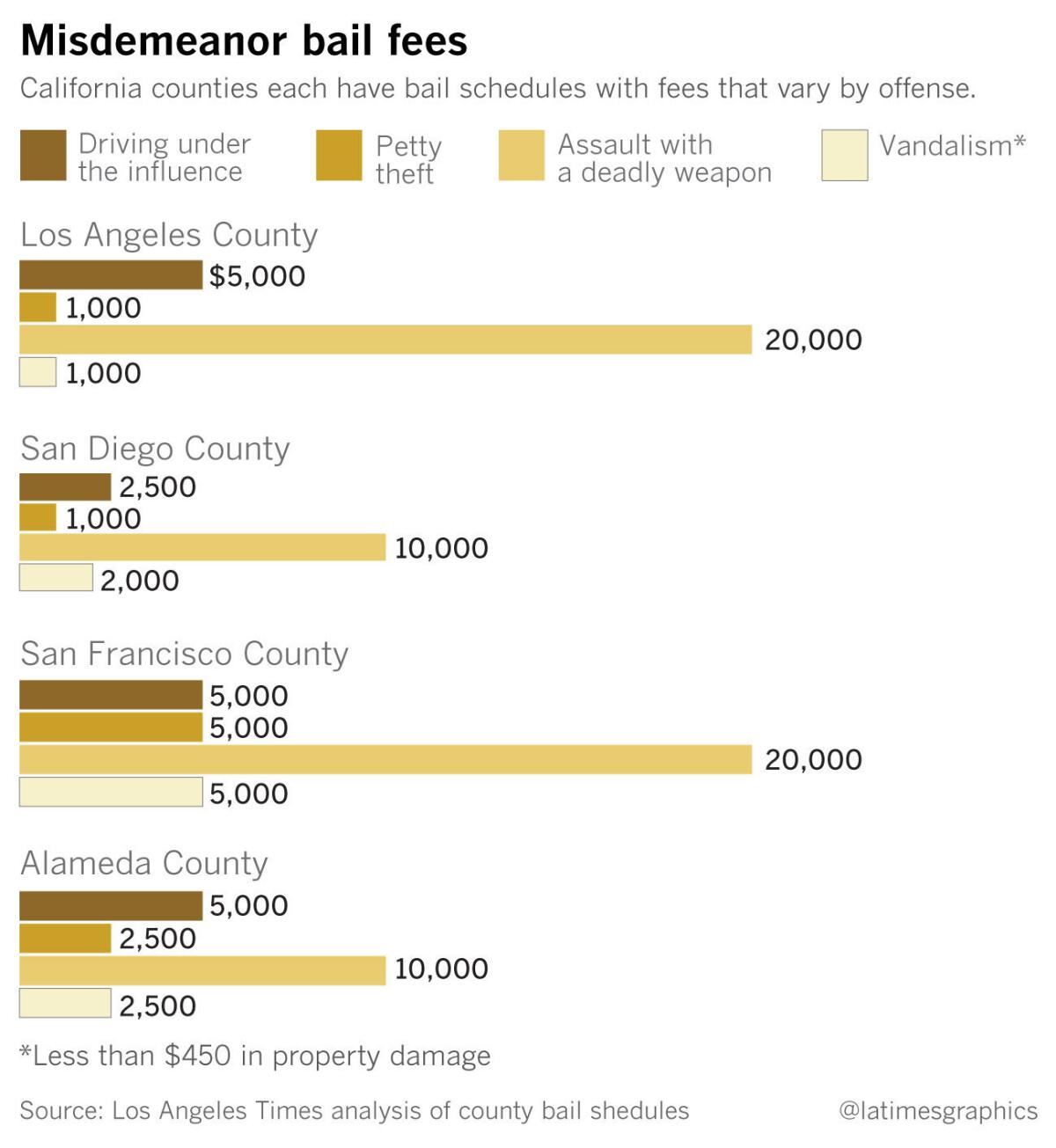

Bail fees vary statewide

A point of contention is the elimination of the “money bail schedule.” There are no statewide standards or uniform fees to apply when courts set bail. Instead, judges in each of the state’s 58 counties craft their own approaches to bail and sets of fixed bail amounts, leading to wide disparities.

Senate Bill 10 would allow judges to assign monetary bail only at the lowest amount necessary to guarantee a defendant appears at his or her next court date. In setting that amount, the court would first have to conduct an inquiry to make sure the person has the ability to pay without having to forgo food, shelter or medical care for themselves or their dependents.

The bill’s opponents have argued in favor of reducing the current fixed bail amounts, rather than doing away with them, and creating greater parity across counties. They cite state law that already prohibits excessive bail and say judges have the flexibility to adjust bail per case.

But reform advocates and national organizations such as the American Bar Assn. and the Conference of Chief Justices have endorsed risk-assessment evaluations over fixed bail systems.

“If you can pay the amount on the schedule, you are released — that is the crux of the bail disparity, and that is what is being challenged,” said Mica Doctoroff, a legislative advocate with the American Civil Liberties Union of California's Center for Advocacy and Policy.

What would reform cost?

Another hurdle to bail reform is uncertainty over the cost.

Many courts in California and nationwide have started changing their bail and pretrial practices in response to lawsuits, or as a way to relieve overcrowded jails. One study found at least 29 cities, counties and states — including Arizona, Kentucky, and New Jersey — have developed risk-assessment models.

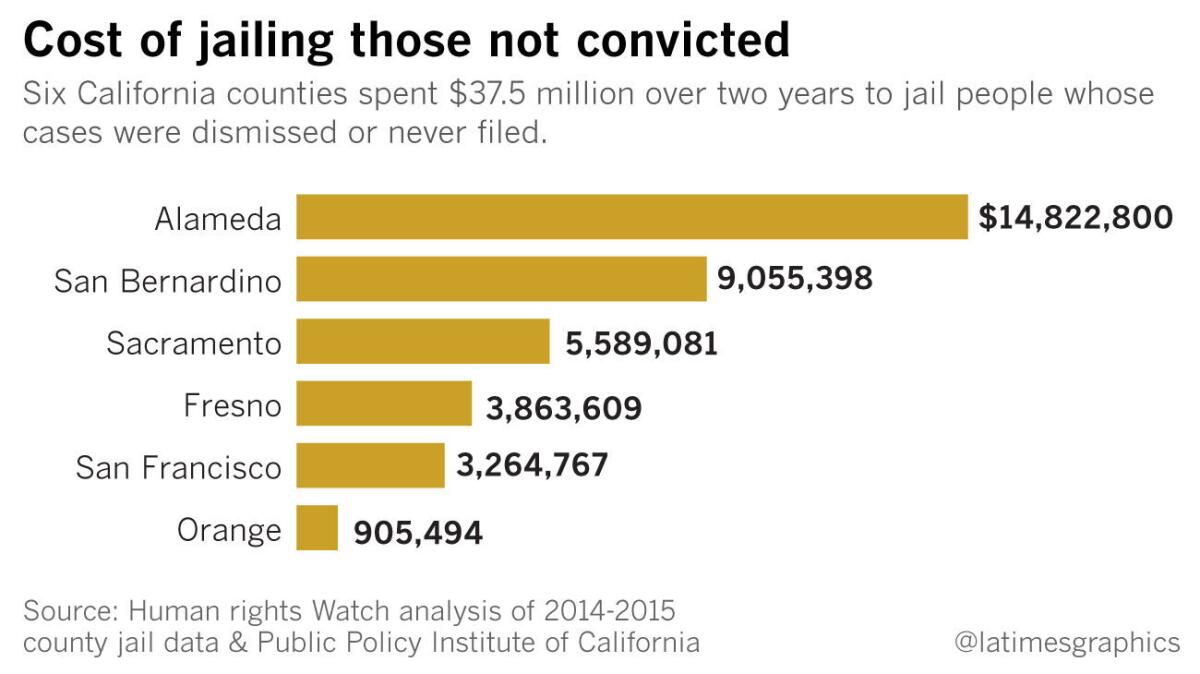

In California, counties including San Francisco, Santa Clara and Ventura have implemented such initiatives in recent years, and officials say there are inherent savings by releasing more people who don’t pose a threat to public safety and have not been convicted of a crime.

But in-depth cost analyses are rare because the county programs are so new, and a report by the Assembly Appropriations Committee showed that getting counties to follow through on the proposed legislation could come with a large price tag.

It concludes that the state would have to spend "hundreds of millions of dollars" to reimburse counties for establishing and administering the new pretrial services. The state would also face ongoing expenses in the tens to hundreds of millions of dollars to pay court-appointed lawyers for defendants, according to the analysis. And it noted costs for future oversight of the new bail system.

A battle ahead

This is not the first time a bail reform plan has been proposed. Former state Sen. Loni Hancock (D-Oakland) authored legislation in 2013 that would have required counties to use risk-assessment tools when preparing pretrial reports for inmates. It passed the Senate but died in the Assembly after heavy lobbying from the bail industry.

This session, bail agents, their lobbyists and even celebrity bounty hunter Duane “Dog” Chapman have argued SB 10 would hurt small businesses, could cost counties up to $2 billion and would increase the number of people wanted on arrest warrants, now roughly 2 million people.

Hertzberg and Bonta said they remain optimistic even after Bonta’s bill stalled on the Assembly floor amid those concerns.

“Bail reform is a national movement,” Bonta said. “It is going to happen no matter what. It is a matter of when, not if.”

On the Assembly and Senate floors, some lawmakers urged their colleagues to hold off until the new programs and risk-assessment models have been studied further. Others suggested waiting until the Pretrial Detention Reform Work Group, appointed by California Supreme Court Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye, releases recommendations on best pretrial detention practices in December.

Last month, Cantil-Sakauye said there was no need to wait to reform the bail system. The work group, composed of 10 judges and a chief executive, is studying pretrial services on its own timeline and is only at the stage of gathering information about what programs exist in California and other states.

Ventura County Superior Court Judge Brian Back, a member of the council, said any of its recommendations would go through a lengthy vetting process, taking into account changes in state law, before courts would have to implement them.

“The legislation is what it is,” he said. “We don’t want that to interfere.”

ALSO:

Legislation to overhaul bail reform in California hits a hurdle in Assembly

Here's how state lawmakers plan to reform the bail system in California

California lawmakers want to reform a bail system they say 'punishes the poor for being poor'

Sweeping reform of California's bail system would come with a hefty price tag, says new analysis

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.