Texas was Obama’s chief antagonist. In Trump’s America, California is eager for the part

Reporting from Sacramento — In the early morning hours after Donald Trump became president-elect of the United States, California Senate leader Kevin de León and Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon were on the phone grappling with what comes next.

Trump’s upset victory left the two Democrats reeling. They saw the incoming administration as an existential threat to the progressive work they accomplished in the nation’s most populous state. By midday Wednesday, they released a combative statement vowing to defend those strides.

“We are not going to allow one election to reverse generations of progress,” they said.

Other California leaders rushed to join Rendon and De León in setting up the state as a liberal counterweight to Trump, laying the groundwork for four years of battles with Washington.

Now, the circumstance in which California finds itself recalls that of a perennial rival: Texas playing the role of chief antagonist to President Obama.

That brand of resistance — a barrage of lawsuits seeking to stymie Obama’s priorities, and an elevation of state identity over a national one — may be a model, albeit an imperfect one, for California leaders wondering where the state fits into Trump’s America. But taking a pugnacious posture would be relatively out of character for a state that in recent times has not tended to view federal power with hostility.

“I think it’s important to think about what California will do if this is a systematic and deeply conservative administration, pushing it in directions it doesn’t want to go,” said Cal Jillson, a political analyst and professor at Southern Methodist University. “Taking a lesson from Texas and learning from the Texas strategy when it feels it is going the wrong way could be wise.”

Trump’s victory immediately put California in a defensive crouch, as leaders took stock of policies that could be threatened under a new administration. A repeal of the Affordable Care Act could put in jeopardy the state’s dramatic rise in residents with coverage. The unprecedented rights extended to immigrants in the country illegally — including deportation relief — is at odds with the president-elect’s vow to crack down on so-called sanctuary cities.

The vast intersection of state and federal policy on healthcare, welfare programs and the environment means the Trump administration’s influence could reverberate throughout California.

Concern over the possible repercussions was particularly acute for Rendon and De León, who as Latinos saw Trump’s win as a personal affront and a danger to the constituents of their immigrant-dense Los Angeles districts.

“These are the big questions that are on the table,” De León said in an interview. “Will there be draconian cuts that impact lunches for senior citizens? That impact quality childcare for single mothers? There are a lot of things that folks have not considered.”

Gov. Jerry Brown, who had joked before the election that California may need a wall built around it in the event of a Trump win, emphasized unity in his first public comments on the election results — complete with a nod to President Abraham Lincoln.

Promising that California will strive to “find common ground wherever possible,” he also pointedly vowed to protect the “precious rights of our people” and to continue to work to combat climate change, which the incoming president has called a hoax.

Other Democratic leaders have struck a more strident note. Secretary of State Alex Padilla lambasted Trump advisors Steve Bannon and Kris Kobach as “direct threats to American liberty, multiculturalism and equal opportunity.” California Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom on Thursday called for state-funded colleges and universities to commit to being “sanctuary campuses” to shield students without legal status from deportation.

Rendon said in an interview he was not necessarily spoiling for a fight with the new administration, but relished the prospect of guarding existing state policies.

“If the president tries to inhibit what we’ve been trying to do, I’m more than happy to be antagonistic toward him,” he said. “I would welcome that.”

Analysis: For reeling Democrats, now what? »

The Assembly speaker also said he’s been ruminating on “what it means to be an American versus what it means to be a Californian.”

The telling distinction echoes the robust sense of identity in Texas, which is heavily invested in its own origin tale as an independent republic skeptical of government overreach.

Former Texas Gov. Rick Perry famously mused on the prospect of seceding from the nation, although he never endorsed the possibility. In the wake of Trump’s win, a movement for a California secession — termed “Calexit” — enjoyed a burst of publicity.

Just as Californians swiftly signaled opposition to the incoming Trump administration, Texans were once quick to disagree with President Obama.

Republican officials in the Lone Star State took a hard anti-Washington, anti-federal government stance soon after Obama entered office. They blocked polices from what they called an overbearing federal government, unfunded mandates and burdensome regulations, using litigation, legislation and actions by state executive agencies.

It was not uncommon for state officials whose duties were not directly affected by the Obama initiatives to chime in, creating a chorus of opposition.

Leticia Van de Putte, a Democrat and former Texas representative, called it the “‘distrustful loyal’ playbook.”

“It was all sue, stall or absolutely refuse to have the conversation,” Van de Putte said.

Among the most useful tools was the court system: The state of Texas sued the Obama administration more than 45 times on healthcare, immigration, climate change and transgender bathroom policies, among other issues.

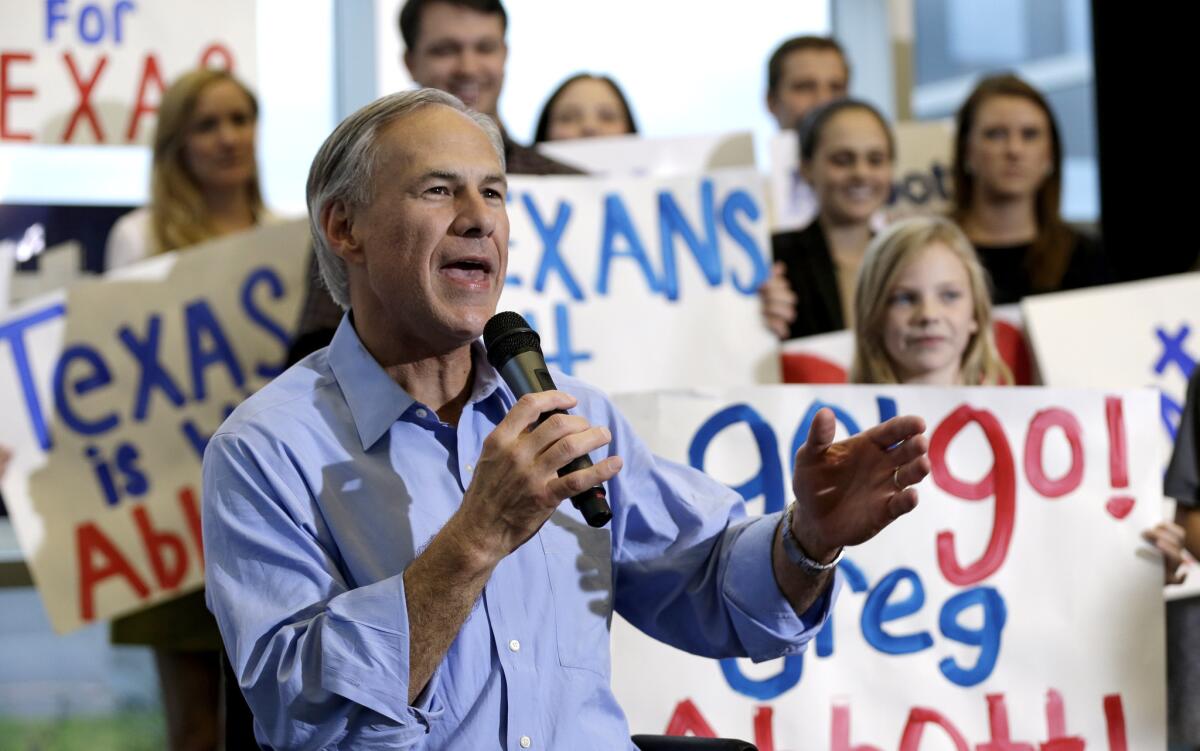

Former Texas Atty. Gen. Greg Abbott filed more than 30 of those lawsuits, and boasted about it on the campaign trail for governor.

“I go into the office, I sue the federal government and I go home,” he told the Associated Press.

“From day one, Greg Abbott started filing lawsuits,” recalled Gilberto Hinojosa, chair of the Texas Democratic party. “He was not always very successful, but in some areas he was.”

The legal challenges often tested when federal laws preempt state laws and the limits of executive power.

The most recent success came this year, when a split U.S. Supreme Court halted an executive order from Obama that would have granted permanent legal status to millions of immigrants brought into the country as children. Texas also made strides against regulations over air quality, greenhouse gases and carbon emissions from power plants.

Abbott and Republican leaders billed themselves as defending the rights of Texans and opposed the government at every turn, mobilizing a coalition of Republican attorneys general in other states to oppose the Obama administration.

Earlier this year, in an attempt to fuel a national debate over states’ rights, Abbott also called for a constitutional convention to diminish the federal government’s power over economic regulation and other issues.

“It didn’t really catch fire, and now with a Republican administration those words will never cross his lips ever again,” said Bill Miller, a Republican political consultant in Texas.

But if California seeks to emulate the Texas strategy, which the GOP used successfully to rally its base, Miller said, it must follow “a litigation model.” “It is going to be a legal fight, and you need to do it consistently throughout the presidency,” he said.

With much of the battle waged in the courts, the extent of California’s combativeness will be determined by who will be the state’s next attorney general. Under Atty. Gen. Kamala Harris, the newly elected U.S. senator, the state Department of Justice is currently analyzing how Trump may impact California in immigration, civil rights, healthcare, the environment and consumer protections.

De León has urged the governor, who has the authority to appoint Harris’ successor, to pick a new attorney general that will aggressively protect existing state policies. A spokesman for Brown has said the goal of finding “the best possible candidate” has not changed with the election results.

The state Senate also plans to hire its own outside counsel for guidance on how to fend off unfriendly directives from Trump, according to a legislative source.

But whether California can follow the Texas playbook and lead a mass resistance against the federal government remains to be seen.

“Texas’ approach has been to challenge the federal government so that Texas can go its own way,” said Case Western Reserve University law professor Jonathan Adler. “What will be interesting to watch is whether California will be seeking to go its own way, or whether California will be seeking to reorientate or guide the policies of the nation.”

ALSO:

Gov. Jerry Brown warns Trump that California won’t back down on climate change

Updates on California politics

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.