Column: California lawmakers say they’ll keep releasing sexual misconduct records. And yet a bill to guarantee that is about to be killed

Reporting from Sacramento — Last October, after accusations of a “pervasive” culture of sexual misconduct in politics blazed through Sacramento, the question was whether the California Legislature would disclose records pertaining to abuse investigations.

The answer, in a limited fashion, was yes. Six months later, the question is whether lawmakers will continue to rely on an ad-hoc process that can be canceled anytime they want. Legislation to ensure access to sexual harassment records has sat in limbo in the state Assembly since January.

And as of now, it looks as though that bill will miss a key deadline and effectively be killed without ever being heard in public.

California Legislature has spent $294,271 investigating sexual harassment claims since 2006 »

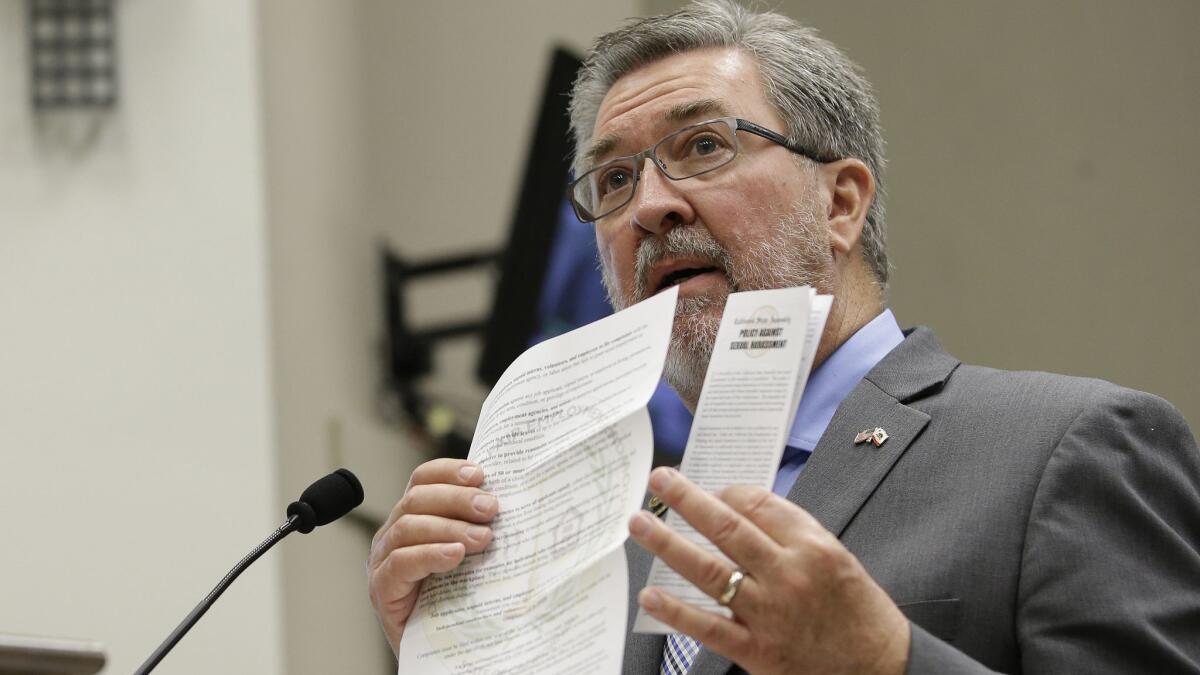

“We need to change the statute,” said Assemblyman Mark Stone (D-Scotts Valley). The proposal in question, Assembly Bill 2032, was written by the committee he chairs. But Stone can’t push the bill forward without action first by the Assembly Rules Committee.

AB 2032 would modify the state’s Legislative Open Records Act, a 43-year-old statute giving lawmakers unique power to shield their internal documents. It would guarantee public access to documents related to “complaints of harassment, discrimination or other misconduct” by a lawmaker or high-level staff member — but only for complaints judged “true” or “well-founded.”

That language wasn’t chosen at random. It’s what Assembly and Senate leaders agreed to in early January, after several weeks of warnings from The Times that their refusal could be challenged in court. In February, legislative officials released documents covering 18 sexual harassment investigations since 2006, and this month produced more documents, some from as far back as 1992.

California’s Legislature has its own disclosure rules, different than those for anyone else »

None of those actions was mandatory. In fact, a top Senate aide said at the time that the disclosure policy would simply be added to the “custom and practices” of the house — guidelines that appear to be even weaker than the standing rules of operation.

Stone believes that such rules can’t be effective under the existing Legislative Open Records Act. “That’s why changing the statute is so important,” he said last week.

On Friday, though, the chairman of the Assembly Rules Committee said he won’t move the bill forward before a live-or-die legislative deadline next month. Assemblyman Ken Cooley (D-Rancho Cordova) said he supports the concept but wants members of a special sexual harassment subcommittee formed last year to lead the conversation instead. “They have to be allowed to do their work,” Cooley said in an interview.

AB 2032 wouldn’t change that process. Even then, the bill could be rewritten with additional guidance all the way through late summer. Its untimely death will strike some as curious, given how non-controversial and narrow its provisions seem to be. The bill does not, for example, offer any explanation for why disclosure of serious sexual misconduct allegations should be limited to “high-level” legislative staff, given that harassment isn’t limited to incidents between a supervisor and his or her subordinate.

In early January, Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon (D-Lakewood) told his colleagues that when it comes to sexual misconduct, they “must become what California is on so many other issues, an example of how to go forward.” Lawmakers can certainly boast they’ve done some of that in 2018. But if the bill in question is killed, transparency in Capitol sexual misconduct cases will continue to be guided by rule of thumb and not the rule of law.

Follow @johnmyers on Twitter, sign up for our daily Essential Politics newsletter and listen to the weekly California Politics Podcast

ALSO:

Updates on California politics

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.