Column: Political Road Map: California’s election maps, drawn without party favoritism, hit the halfway mark

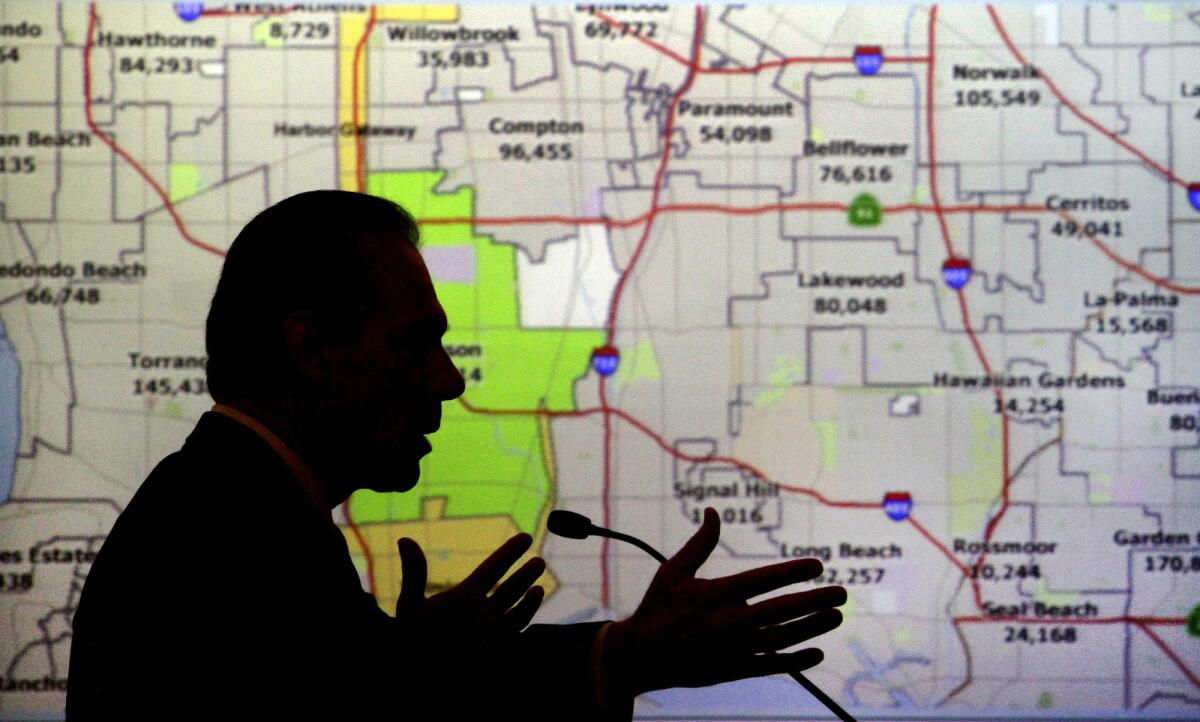

Few arcane topics have broken through the public consciousness in recent years as well as redistricting, the once-a-decade process of redrawing political maps based on changes in population, race and ethnicity.

In dozens of states, voters are starting to understand that it matters where the lines are drawn. And in the vast majority, it’s the state legislators who quietly carve up communities to maximize the political power of whichever party is dominant.

Which is why Tuesday’s election here in California offers a glimpse into an alternate universe, what happens when the maps are drawn in public and guided by a bipartisan panel of citizens. And that panel, selected in 2010 and 2011, made one thing very clear: Data on the impact to Democrats and Republicans wouldn’t be included.

“We didn’t even broach the topic,” said Jodie Filkins Webber, a Riverside County Republican who was one of 14 women and men chosen for the redistricting commission created by voters through ballot measures in 2008 and 2010. “Because we were the first commission, we wanted to make a statement.”

That statement, an officially blind eye to how the new maps would impact political parties, was not required. The voter-approved rules governing map-drawing for the Legislature, the U.S. House of Representatives and the state Board of Equalization said the districts “shall not be drawn” to favor a political party. But the rules do allow the commission to see how many Republicans or Democrats are being lumped together or split apart.

Future commissions may be more lenient on that point; the first panel was unanimous in saying no.

Political Road Map: The radioactive Republican brand in Califiornia »

“We were all in agreement,” said Connie Malloy, one of the citizen panel members who was unaffiliated with any registered party.

Even so, interest groups representing business, labor and minority communities examined each and every potential squiggle on the maps for the net effect on GOP or Democratic political strength. On Aug. 15, 2011, the citizens panel gave final approval to 177 new political districts, letting the partisan chips fall where they may in the 2012 elections and beyond.

This year marks the third of five elections under those districts. Since then, Republicans have lost five of their congressional seats and experienced a shifting but net loss of seats in the Legislature. The party, struggling with a political brand that’s unpopular even among its own ranks, faces tough races in several parts of California this week. But unlike other states, it’s not political gerrymandering that’s being blamed for election results.

Malloy, one of the unaffiliated “independent” commissioners who focuses on voter and civic engagement issues for the nonprofit James Irvine Foundation, believes too many people have seen political parity as a proxy for fair representation.

“Looking at party data is a short cut, and a faulty one, for trying to decide who voters are, and what they care about,” she said.

California’s independent redistricting commission will get new members by the end of the decade, commissioners who will use Census data collected in 2020 to redraw the boundaries. To serve, commissioners must apply through a lengthy and non-partisan process. Thousands of people submitted applications in 2011.

In all, seven states use redistricting commissions rather than legislators to draw political maps. But none are as independent as the California panel, where commissioners said the greatest success may be the end of closed-door deal-making that left citizens with no clue as to what happened, or why.

“What has really come about,” said Filkins Webber, “is greater transparency.”

Follow @johnmyers on Twitter, sign up for our daily Essential Politics newsletter and listen to the weekly California Politics Podcast

ALSO:

Californians are being asked to force transparency in the Legislature

One man is bankrolling the ballot measure that could kill high-speed rail

Updates on California politics

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.