Column: The one-day, $1-billion California budget gimmick that has lasted for almost a decade

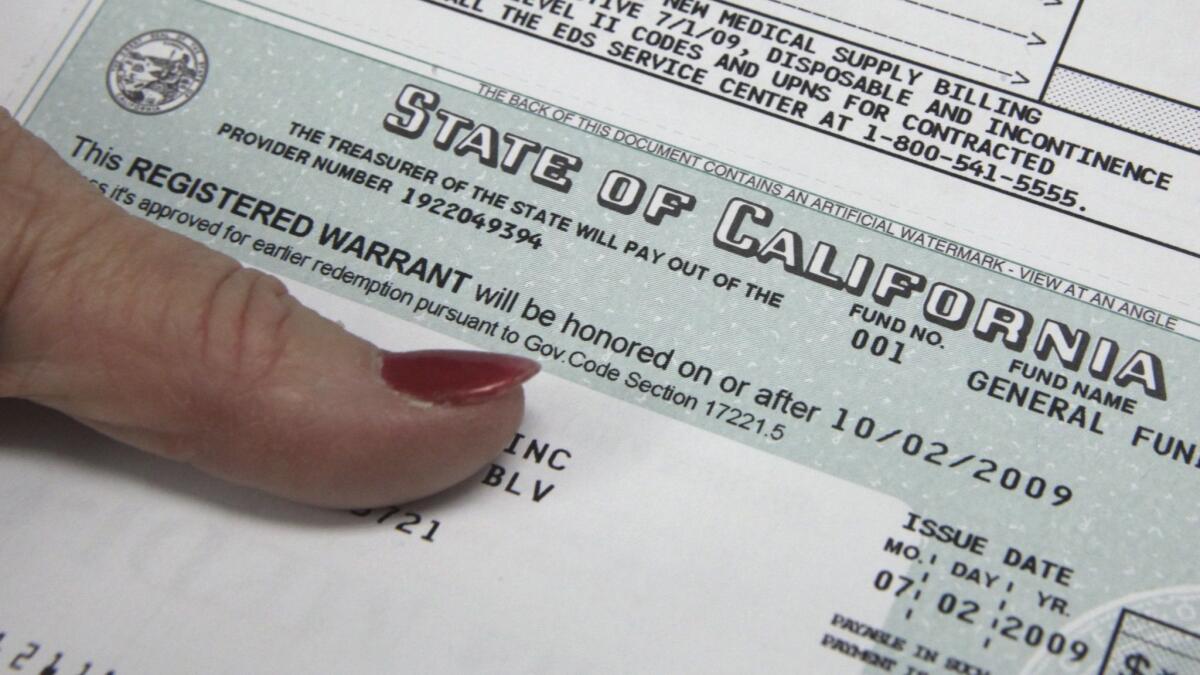

Ten years ago this week, California lawmakers stared into the deepest fiscal abyss the state had ever faced and lived to tell the tale — in part by pretending part of the hole didn’t really exist.

Now, the current crop of state leaders must decide whether they’ll finally stop telling themselves the state spends almost $1 billion less every year just by putting off that spending for a single day.

The budgetary sleight of hand in question, part of a 2009 spending plan, was both brilliant and preposterous. It ordered that $1.6 billion in state worker salaries and benefits scheduled for payment June 30 — the final day of California’s fiscal year — should instead be paid a day later, on July 1. The result was a net decrease in spending, a cut without actually cutting anything.

But for the trick to never actually cost the state money, officials had to keep using it. And so they did: Every year, that month of payroll costs is moved from the final day of one fiscal year to the first day of the next. To do differently would mean that the money would again be considered an extra expense, one likely to be paid by reducing costs somewhere else.

“We’re getting rid of that gimmick,” Gov. Gavin Newsom said last month when he laid out his $209 billion budget plan for legislators to consider.

Newsom’s budget calculates the current value of the one-day payroll scheme at $1 billion a year and proposes scrapping it by using some of the state’s one-time tax revenue windfall. Undoubtedly, he sees that move as a win-win: Ceasing a practice that just keeps pushing a problem forward would also earn him points for being transparent and trustworthy.

Gov. Gavin Newsom embraces an untested idea on how California’s rainy-day fund should work »

He’s not the first to lament the gimmicks of California’s gloomy budget days gone by. Former Gov. Jerry Brown erased billions in costly borrowing started between 2004 and 2011 that he nicknamed the state’s “wall of debt.” Newsom hopes to finish off those payments in the coming year.

But other monetary schemes remain. In 2009, the same year in which the 24-hour payroll shift was enacted, state lawmakers tinkered with deadlines for taxpayers who make estimated payments. The system previously parceled out those payments every 90 days. But it was retooled so more money would arrive in Sacramento early enough to be counted toward a cash-depleted state budget.

Californians whose income taxes come from their paychecks were hit with changes in withholding that meant many paid more sooner and got the money back as a tax refund — in effect, a loan to the state. That system remains enshrined in state law.

Neither Newsom nor lawmakers have proposed ending those budget gimmicks. Nor is it certain his payroll plan will happen, either. Last week, the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office suggested shouldering the one-time cost — about $973 million from the state’s general fund — might not be worth it.

“Instead, the Legislature could use these resources to build additional reserves” to protect against future deficits, the analysts wrote.

That the gimmick has lasted so long is a testament to how hard it can be to undo something that, truth be told, isn’t hurting anything other than the public’s perception of the Legislature.

And Newsom, even as he champions the change, doesn’t deny that desperate times can lead to desperate measures.

“If I use it in six years, in a recession, forgive me,” he said with a smile during his Jan. 10 budget press conference.

Follow @johnmyers on Twitter, sign up for our daily Essential Politics newsletter and listen to the weekly California Politics Podcast

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.