Why a group of first-generation Vietnamese immigrants are voting for a Latino instead of a Vietnamese refugee

Reporting from Garden Grove — On a recent evening, a dozen or so Vietnamese American seniors gathered in Hung Nguyen’s Garden Grove living room. The long table they hunched over was filled with plates of bánh tráng mè, a sesame-studded rice cracker, and peanuts — usually the kinds of snacks reserved for drinking sessions.

But these retirees had work to do: They pored over long lists of names, dialing phone numbers and speaking in lilting Vietnamese, trying to convince fellow Orange County voters to support their candidate for Congress: Lou Correa.

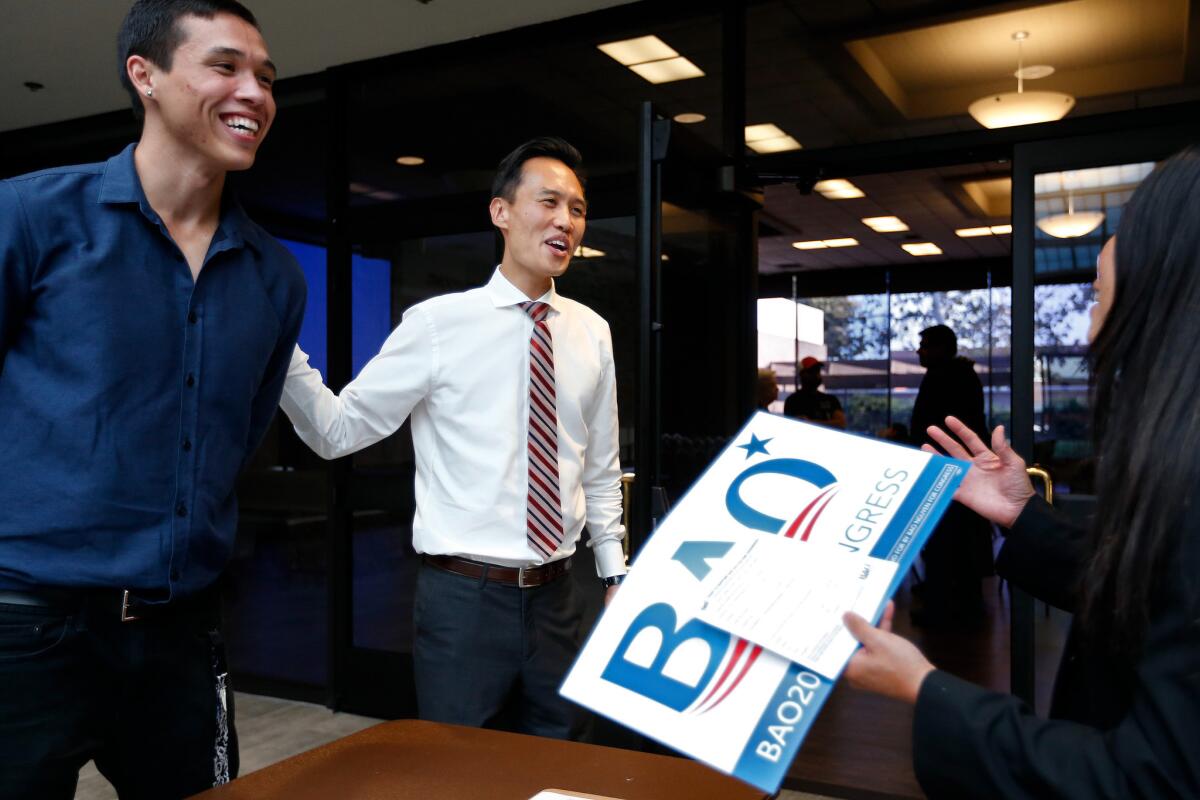

It’s not the most obvious choice for these first-generation immigrants, many of whom came to the United States as refugees. Correa, a seasoned Latino politician and former state senator, is running against Bao Nguyen, the 36-year-old mayor of Garden Grove who grew up in and around Little Saigon and who himself was born a refugee in the aftermath of the Vietnam War.

But Nguyen isn’t the kind of politician most Vietnamese Americans are used to seeing — or supporting — in Little Saigon. A gay, charismatic progressive who endorsed Bernie Sanders for president earlier this year, Nguyen has taken unpopular positions in the historically conservative Vietnamese community, where nearly all home-grown politicians have been Republicans. (The first Vietnamese American elected to Congress, Anh “Joseph” Cao of Louisiana, was a Republican who lost his seat in 2010 after just one term.)

When Nguyen and Correa, both Democrats, face off in November for the 46th Congressional District seat now held by Rep. Loretta Sanchez, it will be a test of how far the loyalties of this politically organized ethnic voting bloc can stretch.

“I voted for Bao Nguyen when he ran for mayor, because it was important for us as Vietnamese people,” Nancy Nguyen, a phone banker and Garden Grove resident, said in Vietnamese. “But he has very little experience, and Lou has a long career helping the Vietnamese community…. When I have to make a choice between the two, he’s my choice.”

Correa, for his part, has become something of a household name throughout central Orange County over the years, having served here as a state assemblyman, state senator and county supervisor. The former investment banker is known as an old-school retail campaigner who has built support in both Latino and Vietnamese communities, and he pitches himself as a “common sense” Democrat who can stretch across the partisan divide to serve constituents. Correa, 58 has backing from a vast array of establishment Democrats, including Sanchez and House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco), as well as the California Democratic Party, business groups and more than half a dozen labor unions.

He likes to bill himself as a “homegrown” candidate who grew up a few blocks from his campaign office — someone who has built a reputation as a moderate serving his district, not party interests, first.

“This is a blue-collar, hard-working immigrant district, and that’s what my parents were,” Correa said. His campaign style echoes that of Sanchez, who has shown up to community events wearing the traditional áo dài tunic and, like Correa, has been known to hire Vietnamese American staffers.

Nguyen, a former union organizer for the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees who also served as a Garden Grove school board member, earned a masters degree in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism from Naropa University in Colorado. He has endorsements from liberal groups including the Sierra Club, Equality California and the California Nurses Assn., as well as the Mexican American Bar Assn. PAC. Nguyen says he’s banking in part on support from millennials and supporters of Sanders, who beat Hillary Clinton by two points among the district’s Democratic voters in June.

But Nguyen has a long row to hoe: Even after a come-from-behind victory in which he beat out former state Sen. Joe Dunn, he received 14% of primary votes to Correa’s 43%. Nguyen also lags in fundraising, receiving less than $197,000 in contributions to Correa’s nearly $590,000 as of June 30. Correa also benefited from $101,752 in spending by the Latino Victory Fund and $535,439 of independent expenditures by the National Assn. of Realtors Congressional Fund.

Nguyen is no stranger to being the underdog: He beat out a 22-year incumbent by just 15 votes when he was elected Garden Grove’s first Vietnamese American mayor in 2014.

“We’re building a broad coalition based on progressive values,” Nguyen said in an interview at his Santa Ana campaign office. “That is a more realistic way of campaigning these days.”

This is not the first time Latino and Vietnamese candidates have squared off here.

After beating Republican Bob “B-1” Dornan in 1996, Sanchez twice ran against Vietnamese American Republicans. In 2006 Republican Tan Nguyen, a former Democrat who ran on a platform opposing abortion rights and halting illegal immigration, lost by nearly 25 points. The race had turned ugly after the Republican’s campaign sent 14,000 letters in Spanish that said it was illegal for immigrants to vote, causing his own party to disavow him.

Two years later, Sanchez faced former GOP Assemblyman Van Tran, who mounted a competitive challenge. In the heat of the campaign, Sanchez told a Spanish-language television station that “the Vietnamese and Republicans” were trying to take away her seat. She described Tran, himself an immigrant, as “anti-immigrant” and “anti-Hispanic.” She won by 14 points.

Will it be different with two Democrats on the ballot? Ethnic politics have always been a significant factor in this district — Vietnamese Americans have been known to turn out for Vietnamese candidates, and the same can be said for Latinos, who, despite their advantage in registration, don’t vote at high rates.

Correa knows this well: He lost his 2015 bid for Orange County supervisor to a Vietnamese American Republican by just 43 votes, largely because of the outsize impact of voters in Little Saigon, where voters were twice as likely to turn out than the Latino-heavy city of Santa Ana. Only 12% of Latino voters cast ballots in that special election, compared with 41% of Vietnamese voters, according to a Times analysis.

Correa attributed his loss to the mobilization of a Vietnamese American turnout “machine.”

I didn’t get involved in politics because of anti-communist Vietnam homeland politics.

— Garden Grove Mayor Bao Nguyen, candidate for 46th Congressional District

Vietnamese American voters in Sanchez’s district once had that kind of influence: Before redistricting shifted the boundaries, they made up 13% of registered voters, the highest proportion of any California congressional district. But a large swath of Little Saigon was cut out of the district after 2010, and Vietnamese voters now comprise just 7% of the electorate.

“Even at 7%, the Vietnamese pack a punch,” says Fred Smoller, a political science professor at Chapman University. “They vote by mail, they vote at very high rates, and they vote Asian.”

But Nguyen has an uphill battle to win many of them over.

SIGN UP for our free Essential Politics newsletter >>

Born in a refugee camp in Thailand and arriving in the United States as an infant, he often tells the story on the campaign trail of how, when he became a naturalized citizen at age 12, an immigration officer asked if he would like to choose an “American name” like his parents had. He says his reply was, “My name is American.”

As a college student at UC Irvine, Nguyen showed up to a rally in Little Saigon where much of the community had gathered to welcome Sen. John McCain with open arms.

He and his friends wore white t-shirts scrawled with “American Gook” to protest the presidential candidate’s slur during the 2000 campaign. McCain, who spent five years as a prisoner of war, initially refused to apologize for using the term to describe his North Vietnamese captors before vowing to never utter it again.

Last year, when community members urged the Garden Grove City Council to ask Riverside to drop its relationship with a Vietnamese sister city, Nguyen lobbied against it, saying, “Garden Grove should not tell another American city what to do.” Some audience members, who criticized dealings with the Vietnamese regime as an affront to those who escaped, called for his ouster.

“I didn’t get involved in politics because of anti-communist Vietnam homeland politics,” Nguyen told The Times. “I can represent the parts of who I am where we intersect with other people in our diverse community…. We grew up together in a diverse, multiracial, multi-ethnic culture.”

The candidate’s views on these issues are one reason Hung Nguyen, a former Vietnamese marine who has hosted the Correa phone banking sessions for weeks now, can’t support Bao Nguyen for Congress. The volunteer, no relation to the candidate, says Correa remained fiercely loyal to his supporters in the community, in and out of elected office.

Plus, he has concerns about Bao Nguyen’s “lifestyle.”

“For my generation, things like your… sexual orientation, transgender issues… that still bothers us,” says Nguyen, 70, who says he’s a devout Catholic. “Deep down, people don’t like it.”

Tam Nguyen, also supporting Correa, says that has nothing to do with his choice. He said he has no reservations about supporting a gay candidate, even as older Vietnamese Americans don’t feel the same way.

The 42-year-old owner of Advance Beauty College and former chair of Orange County’s Vietnamese American Chamber of Commerce says Correa’s service to the community is “not just a onetime deal. It’s consistent and long-term.”

What matters to him, Nguyen said, is how as a state senator, Correa organized a town hall meeting at his beauty school to hear from salon owners and state and federal regulators.

“Unlike a generation ago, I believe in making decisions that are best for the community, and that takes into account other major factors beyond ethnicity,” he said.

For more on California politics, follow @cmaiduc.

November intraparty showdown could unseat longtime Silicon Valley congressman Mike Honda

Why Loretta Sanchez is struggling to wake up California’s sleepy Senate race

8 things to know about Senate hopeful Loretta Sanchez’s 20-year political career

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.