California hiked its gas tax for road repairs, yet ‘poor’ bridges have multiplied, data show

Reporting from Sacramento — When large chunks of concrete fell from the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge in February, temporarily closing the major traffic artery across San Francisco Bay, motorists were reminded of longstanding concerns over California’s aging road system that drove the state to raise the gas tax in 2017 to pay for repairs.

The state has spent $121 million of the gas-tax revenue on bridge and culvert projects so far, completing the repair or replacement of 89 bridges. But some elected officials are saying work isn’t happening quickly enough as new data from the Federal Highway Administration show the number of California bridges in “poor” condition has continued to increase since the tax hike.

Republican critics of Senate Bill 1, which raised the gas tax by 12 cents per gallon and boosted diesel taxes and vehicle fees, are calling for reform measures, including the expediting of environmental reviews and tougher oversight to ensure the revenue is used as voters intended. An additional 5.6-cent increase in the gas tax takes effect July 1.

“I’m concerned and disappointed at the pace of repairs,” said Assemblyman Vince Fong (R-Bakersfield), vice chairman of the Assembly Transportation Committee. “Californians are rightfully upset.”

The size of the bridge-repairs backlog is significant, according to the data, released in mid-March.

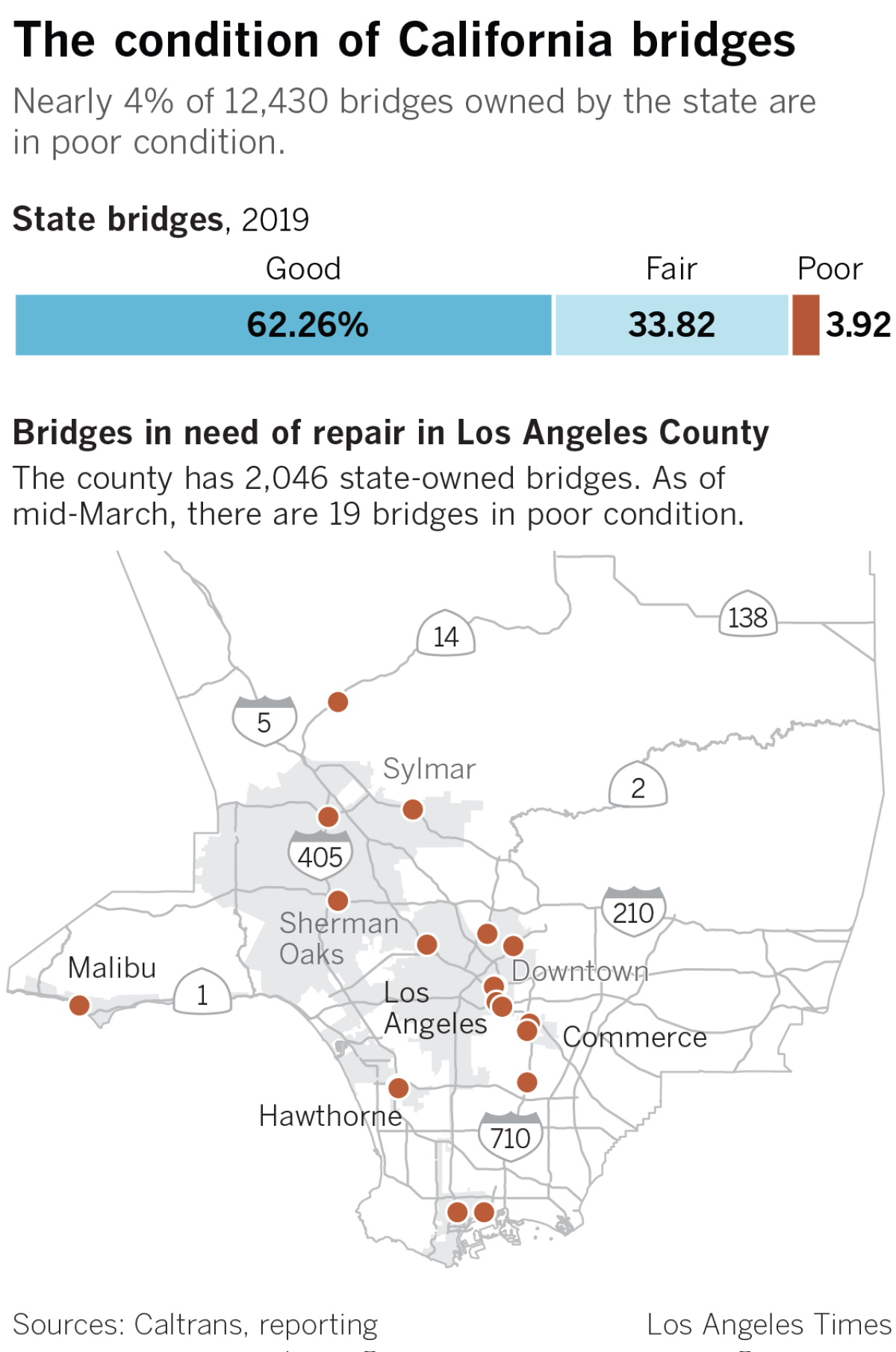

The federal government’s figures show the number of California bridges in “poor” condition has increased in the last three years from 1,204 to 1,812, or 7% of state bridges. The number of bridges in “fair” condition as of last year also increased to 9,146 structures, or 35% of all bridges in California.

During the three-year period, the number of bridges in “good” condition in the state declined from 16,788 to 14,779, or 57% of bridges.

Caltrans officials blame the worsening numbers on a lag in inspections — which take place every two to four years — as well as the aging of the state’s bridges and the fact that bridge repair projects can take three to five years to complete.

“Due to normal wear and tear on our system, and the gradual and methodical inspection procedures, these reports will not instantaneously reflect the historic and crucial investment of SB 1 funding into our state highway system,” said Lindsey Hart, a Caltrans spokeswoman.

A “poor” rating means that one or more components of a bridge may need repair, closer monitoring or weight restrictions so that it does not become unsafe for public travel, officials said. A “fair” rating means that one or more components of the bridge may need preventive maintenance to address deteriorating conditions.

“It’s important to note that a bridge with a poor or fair rating does not mean the bridge is unsafe,” Hart added. “Any bridge deemed unsafe for travel is closed to traffic immediately. Ratings of poor or fair are often a reflection of the bridge’s age and mean the bridge requires additional maintenance and repairs.”

Republican lawmakers say state government inefficiency has allowed California’s backlog of needed infrastructure repairs to grow despite taxpayers packing state coffers with more than $3 billion in new gas-tax dollars so far.

“When we debated SB 1,” Fong said, “one of our biggest arguments was we need real structural reforms to fast track the use of transportation dollars to build infrastructure.”

Fong was unable to win Democratic support for legislation aimed at cutting bureaucratic red tape for transportation projects, including expediting the environmental review process. He also proposed creating an independent inspector general position outside the California Department of Transportation — under SB 1, the position is within the agency.

Lawmakers from both parties have grown anxious since Gov. Gavin Newsom has threatened recently to withhold SB 1 money from cities that fail to meet goals for developing affordable housing. Earlier this month, he said any such action wouldn’t happen before 2023.

Meanwhile, Caltrans officials say they are chipping away at the backlog — even if their progress is not yet reflected in the numbers reported to the federal agency.

Among state-owned bridges, the number in “poor” condition increased from 353 two years ago to 487 as of this year, according to figures released Monday. As a result, 3.9% of state-owned bridges are in “poor” condition. More bridges are also rated “fair” while the percentage of state-owned bridges in “good” condition has dropped from 75% in 2017 to 62.2% as of the most recent figures for this year.

Many more bridges rated poor and fair are owned by cities and counties that also receive revenue from the tax increase.

In 2019, Caltrans is scheduled to begin improving or replacing an additional 378 state-owned bridges statewide, officials said.

Ongoing projects include the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge, which was closed for hours after football-sized pieces of concrete fell from its upper deck to the lower deck. Caltrans determined that, “out of an abundance of caution,” it would replace 62 joints on the bridge this year starting with those on the upper deck, forcing the closure of some lanes at night, Hart said.

The bridge was rated in “fair” condition based on federal guidelines and biennial inspections by Caltrans engineers, she said.

Amid criticism over the pace of work, Caltrans officials say the work done on other highway projects is significant.

The California Transportation Commission has approved $3.1 billion in SB 1 funds for highway improvement projects so far, with an equal amount going to cities and counties.

Since the legislation was approved in 2017, state crews have repaired some 2,900 potholes, replaced or repaired more than 1,300 lane miles of pavement, fixed 37,500 feet of guardrail, replaced or repaired nearly 950 highway lights and traffic signals, and re-striped more than 2,000 miles of highway to improve visibility and safety, Hart said.

Sen. Jerry Hill (D-San Mateo), who supported SB 1, said he was seeing streets being repaved all over his Bay Area district.

“The problems that we are seeing if you are looking at the bridge and the new potholes that we are feeling now are really a result of the neglect that prompted SB 1,” Hill said. “I think it’s going to take time to correct the deficiencies of the last 15 years because that’s the length of time that we have been without those funds.

“It can’t happen overnight.”

Sign up for our Essential Politics newsletter »

Twitter: @mcgreevy99

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.