Parents ask: What happens to my child if I’m deported?

Immigrants ask: What happens to my child if I’m deported?

The questions started pouring in immediately.

Am I at risk of being detained even though I haven’t committed any offenses?

What should I say to ICE if they ask me where I was born?

Will massive raids happen in public spaces?

As the Trump administration released its new immigration rules, immigrant rights groups have been grappling with an uptick in concerns. One of the most common: What happens to my child if I’m sent away?

In the United States, there are roughly 5 million children under the age of 18 with at least one parent who’s living in the country illegally. About 79% of those adolescents are U.S. citizens, according to the Migration Policy Institute.

According to the Pew Research Center, 10% of the 11.1 million immigrants who are living in the country illegally live in Los Angeles and Orange counties.

The details of Trump’s immigration crackdown remain blurry. He has talked about mass deportations, but has also said he wants to focus on individuals who have criminal records. The latter was also a focus of the Obama administration’s immigration policy.

The lack of specifics has fueled rumors and fears in immigrant communities.

Trump’s promised crackdown has won praise from supporters who say people who broke the law coming into the country should be sent back, no matter how long they’ve lived here. But others have strongly criticized the president’s tough rhetoric and say it’s cruel to tear apart families.

I can't expose them to the dangers.

— Guadalupe Galindo, who has lived in the U.S. illegally for 29 years, on the prospect of taking her children with her if she's deported to Mexico

Guadalupe Galindo, 46, has lived in the United States for 29 years. If she’s sent back to Mexico, she would leave her 10- and 8-year-old girls in the care of her 24-year-old daughter. Though she says the distance would be painful, she won’t fathom an alternative.

“I can't expose them to the dangers,” she said about life in her native country.

She has kept her two younger girls in the dark, protecting them from worry. The weight of reality falls on her oldest daughter’s shoulders.

“It's one thing being a sister, and it's another thing to take responsibility like a mother,” Galindo said. “Like taking them to school, and like a mother, representing them in everything.”

For others, permanent separation isn’t an option.

Mario Castillo is a father of two — one 5-year-old and one just shy of 2. If deported to El Salvador, he and his wife plan to leave the children with someone in the United States who could send them on later, aware of what that might mean for their future.

“They’ll be living a different life than the one they deserve here. They were born here,” he said.

They’ll be living a different life than the one they deserve here.

— Mario Castillo, who says he'll have his children sent from the United States to join him and his wife in El Salvador if they're deported

Every case is different, and immigrant rights groups suggest that anyone fearing deportation make a plan and meet with a lawyer before the situation escalates.

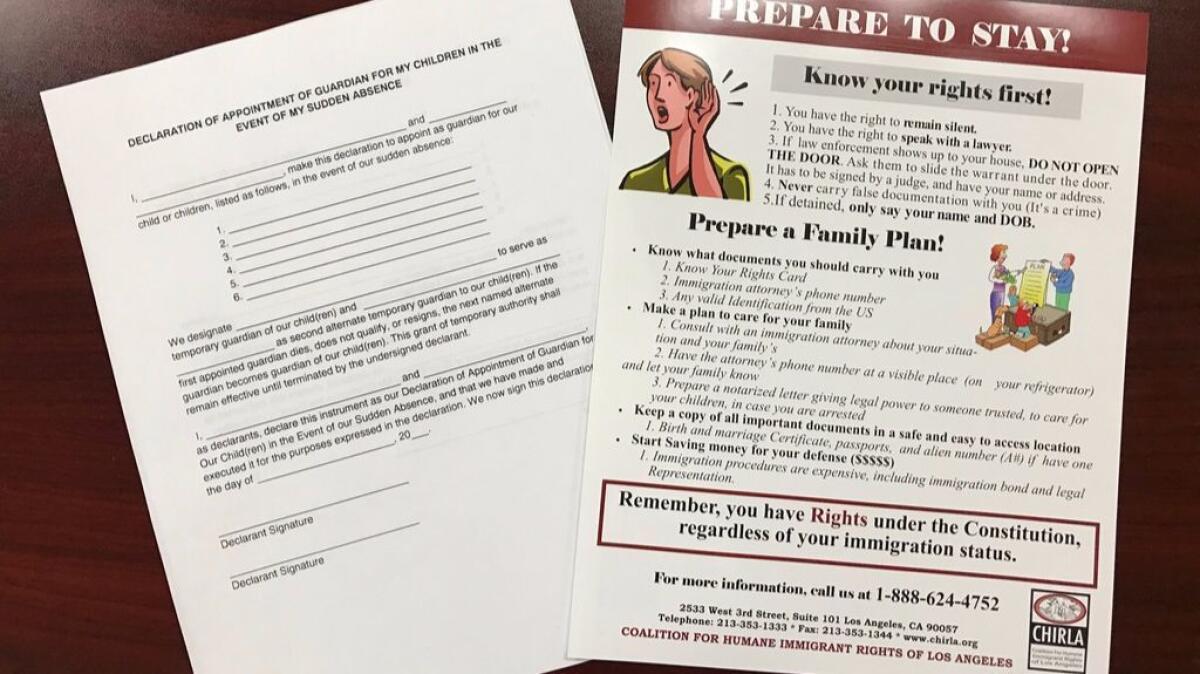

Groups such as the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles (CHIRLA) and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) advise people who are detained by authorities to give only their name and date of birth, request an attorney, hand over a “rights card,” which provides this information in both English and Spanish, and then remain silent. Individuals are also advised to ask to see a warrant before opening the door to law enforcement, and to keep valuable documents such as birth certificates and passports in an accessible and safe location.

Immigrant rights organizations have been actively distributing and notarizing guardian slips for their children to help families prepare for such a scenario. Parents are instructed to write down the names of those they’d trust to watch over their children. If deported or detained, their child would become the immediate responsibility of one of the guardians on their list.

CHIRLA has handed out at least 250 guardian slips in the three weeks since reports of new U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement sweeps circulated, according to Jorge-Mario Cabrera, the group’s director of communications. Last year, they handed out about 25 in total.

The decision of who to name as guardian is not made easily. For parents of disabled children, it’s foreboding.

One couple spoke anonymously through their lawyer, Erika Pinheiro of the Central American Resource Center (CARECEN) immigrant rights group in Los Angeles. The father, originally from Mexico, and mother, originally from Central America, worry most about their middle child, a 10-year-old with learning disabilities and mental health issues.

“He’s been shaking and crying. He doesn’t want to sleep by himself anymore. He’ll wake up and want to sleep with his parents,” Pinheiro said, translating the parents’ Spanish to English.

At a recent Know Your Rights workshop at CHIRLA, a room that typically a couple of dozen Latinos would be learning what they should and should not do or say if stopped by ICE officers was packed and brimming with kids.

Some were too young to understand the growing fear of deportation their mothers and fathers faced. Others were old enough to know all too well. While the smallest played with toy trucks and tumbled at their parents’ feet, those teetering between tween and teen sat patiently. One girl steadfastly took notes as her mom and dad listened intently to instructions at the edge of their seats.

Maria Rosas, a 36-year-old mother of four boys, attended the meeting to figure out a plan. She has already told her children not to be afraid. If she and her husband are deported, they won’t leave them behind.

“Whatever happens, we'll always be together.”

We asked immigration rights groups what type of questions they’ve been receiving. Now we want to hear from you. What kinds of questions or conversations have you been having since the Trump administration released its new immigration rules? Tell us below.

Times staff writer Steve Saldivar contributed to this report.

Twitter: @cshalby

ALSO:

Deportation of grandmother leaves a San Diego military family reeling

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.