Many women thought Clinton would shatter the glass ceiling, not run into a concrete wall

It turned out that the ceiling was made not of glass, but reinforced concrete.

At least that is what it felt like to many women who had been getting ready Tuesday to pour champagne in celebration of the first female president of the United States.

It soon became clear that the nation’s 45th U.S. president would be the 45th man to hold the title, and Hillary Clinton, the woman many had expected to break the biggest gender barrier of them all, would be an also-ran for the nation’s highest office.

In the years to come, political scientists will ponder to what extent gender was a factor in the electorate’s rejection of a candidate with an Ivy League law degree, three decades of public service, a famous surname and the endorsements of a broad swath of newspapers and political leaders.

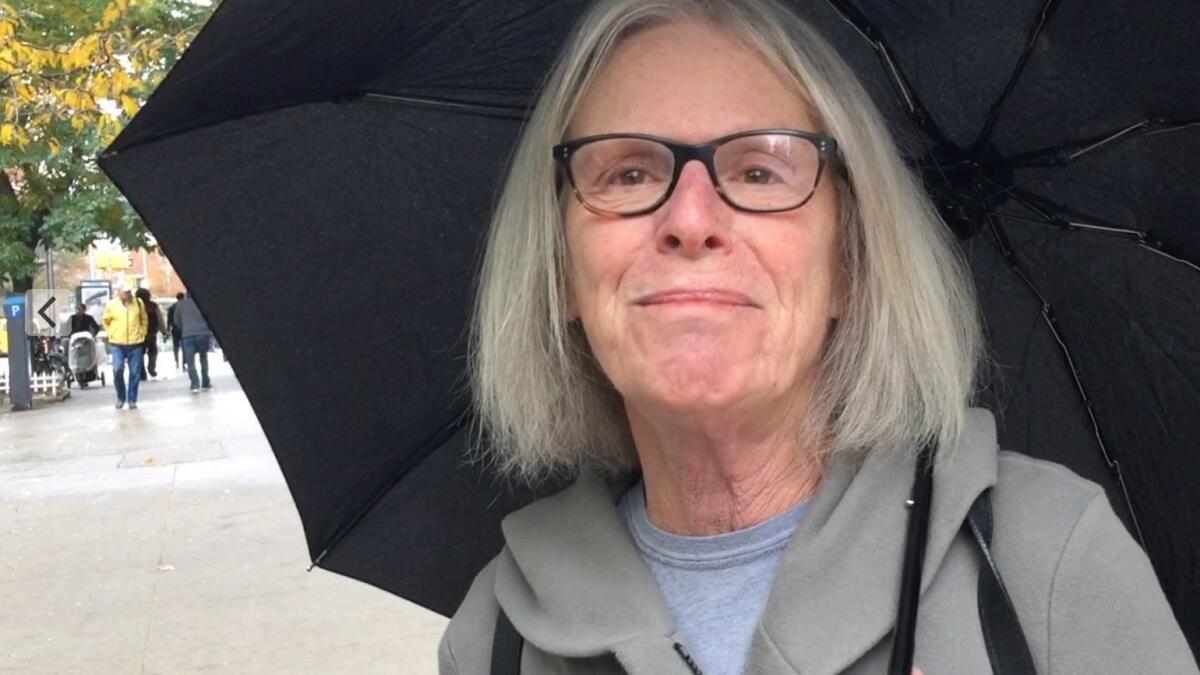

“If she can’t do it, what woman can?” asked Avis Miller, 71, who graduated from Wellesley College three years before Clinton, and who defied gender expectations herself when she became a rabbi.

In interviews across the country, women said the acrimonious presidential campaign had revived long-suppressed memories: of the unwelcome hand on the knee, the backhanded compliment, the condescension, the impossible competition between family and career — terrain that has become much easier for younger women to navigate, thanks to the work done by women of Clinton’s generation.

Before Clinton’s loss to Republican Donald Trump, Miller had planned a celebratory Sabbath dinner with some of her Wellesley classmates, all accomplished women: a professor, an architectural historian, a published novelist.

“There’s that level of accomplishment and achievement — but another level we just can’t seem to crack,” she said.

“A lot of people are very misogynist,” said Jan Greenberg, 73, a theater director who was grimacing as she walked past a rack of news headlines in New York on Wednesday morning. “They don’t admit it — they don’t think they are — but it was going to be very hard for a woman, particularly Hillary Clinton.

“I can’t say exactly where it was, but I felt like misogyny permeated the entire campaign. It was the same as the racism with Obama.’’

Clinton’s defeat, following eight years of Barack Obama’s breakthrough as the first African American president, suggests to many that gender can be a bigger obstacle than race.

“Between sexism and racism, I could say that sexism is definitely the stronger of the two areas of discrimination,’’ said Sheila Talton, the 64-year-old head of Chicago-based Gray Matter Analytics, who as an African American woman has ample experience with both.

Jacinta Camacho Kaplan, a 65-year-old architect who now lives in Santa Monica, was raised with a wild streak. Her grandmother used to roll her own cigars and advised young women they would be old enough to have sex when they knew how to put on a condom.

Kaplan’s father, on the other hand, insisted she go to cooking school because he doubted a woman could make a living as an architect.

Despite its disappointing end, Clinton’s candidacy allowed Kaplan to marvel at how much had changed since she was growing up. She was struck by something her 7-year-old granddaughter recently told her.

“Nana, you don’t have to say I’m pretty. I know I’m pretty. I’m also smart and I play chess. And I’m good at math,” the girl said.

In her concession speech in New York, Clinton struck an encouraging tone about women in politics, addressing her remarks to “all the little girls who are watching this.’’

“Never doubt that you are valuable, and powerful and deserving of every chance and opportunity in the world to pursue and achieve your own dreams,” she said. “I know we have still not shattered that highest and hardest glass ceiling, but someday someone will, and hopefully sooner than we might think right now.”

Clinton’s remarks, however, were scant consolation to women of her own generation. Many of them saw her candidacy as one of their own lifetime achievements — and now are left to wonder whether they will live to see a woman in the White House.

“Will there be a woman president before I die?’’ 69-year-old Sylvia Farina of Lakeland, Fla., said after watching Clinton’s concession speech on television with her 94-year-old father. Both were in tears. “Maybe if Michelle Obama runs.”

Retired from a job as chief of staff to a county commissioner, Farina had seen Clinton’s struggles in parallel with her own experiences as a single mother navigating the lower levels of the political arena, where she endured condescending remarks about her looks and was told when she was laid off that, as a woman, her “husband could take care” of her.

Clinton’s election was going to change all that, she said. “What an opportunity we blew.’’

But not all women — and not even all feminist women — voted for Clinton. Exit polls published Wednesday by CBS News said that white women voted 53% to 43% for Trump over Clinton.

Some women, especially Trump supporters, rejected the idea that Clinton’s defeat should be attributed to her gender.

“It’s too much of an easy, simplistic answer to say, ‘She didn’t win because she was a woman’.… It’s an immature reaction, designed to make [people] feel better, rather than face the actual issue — that many people think she is very untrustworthy,’’ said Wendy Shashoua, 70, from Johns Creek, Ga., an affluent suburb of Atlanta.

A conservative Christian by her own description, Shashoua, who runs a framing shop, said she would have liked to vote for a female president. But more important, she said, was that Trump shared her beliefs about immigration and appointing conservative justices to the Supreme Court.

Of course, women have always been at a considerable disadvantage in electoral politics.

“I hate to say I told you so, but everything I have done as far as my research shows that this is a tough road for a woman to climb,’’ said Farida Jalalzai, a University of Oklahoma political scientist specializing in female leaders. “If they are able to break through the glass ceiling, they have to have extraordinary credentials and family ties.’’

In her book “Shattered, Cracked or Firmly Intact,” Jalalzai studied 115 women who have held top offices around the world since 1960. Of them, fewer than one-quarter managed reach the top through a popular vote. Many of those rode to power on the name recognition of a powerful male relative — a husband, father or brother.

A total of 16 out of 252 world leaders today studied by Jalalzai are women.

Another study last year by the Pew Research Center reported that 63 out of 142 countries studied had at some point had a female head of state in the last half-century, but they often did not serve out their full term.

Examples include Brazil’s Dilma Rousseff, who was impeached earlier this year on corruption charges spearheaded by a male opponent who was also under investigation for corruption. South Korea’s Park Geun-hye is also facing threats of impeachment in a murky case involving a family friend said to have exercised undue influence.

In regard to the recent election, many women said that what injected gender into the debate was not Clinton being a woman but Donald Trump’s behavior — his taunting of Clinton and her supporters, his recorded remarks about groping women, and his debate invitation to women who had accused Bill Clinton of sexual impropriety.

“Through this campaign, I can see this country is still very sexist,” said Assunta Ng, who publishes newspapers that target the Seattle area’s diverse Asian population, and is in her 60s. “America is the most progressive country in the world, but this attack, attack, attack on a female presidential candidate is something very hard for outsiders to understand.”

“Obviously, this country is just not ready for a woman in leadership,’’ concluded Jody Silver, 61, a New Yorker who runs a mental health network in New Jersey. “It is an embarrassment for us.”

This story was reported by Jenny Jarvie in Atlanta, Gale Holland in Los Angeles, William Yardley in Seattle, Nigel Duara in Phoenix, Laura King in Washington, D.C., and Barbara Demick in New York.

ALSO

‘Calexit’ movement says Trump win helps their calls for California to secede

In wake of Trump’s win, even some in Silicon Valley wonder if Facebook has grown too influential

Now Trump has his chance to change Washington. But it might change him instead

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.