Trump isn’t much for selling the public on trade-offs. Too bad for him, rewriting the tax code depends on it

President Trump isn’t a fan of compromise when it comes to changing laws. (April 17, 2017) (Sign up for our free video newsletter here http://bit.ly/2n6VKPR)

Reporting from Washington — One of the biggest stumbling blocks to President Trump’s failed efforts at passing a healthcare bill turned out to be his own words — promises of insurance for everyone, lower costs and better care — which can’t all be achieved at the same time.

For a president who likes to make gold-plated policy sales pitches, Trump’s next attempt at a major legislative achievement poses an even stiffer challenge. Overhauling the tax system, perhaps more so than the healthcare system, cannot be done without creating winners and losers.

And Trump, even more than typical politicians, dismisses the notion that he needs to sell the public on making trade-offs, often promising that changing laws will be “beautiful” and “so easy,” and that compromises made in the past were the result of “stupid politicians” who forged bad deals.

Yet rewriting the tax laws depends on a strict diet of tough choices. Want to lower tax rates for everyone without killing popular deductions or driving up the deficit? Good luck. Want to raise money with a consumption tax without hiking prices at Wal-Mart? Nice try.

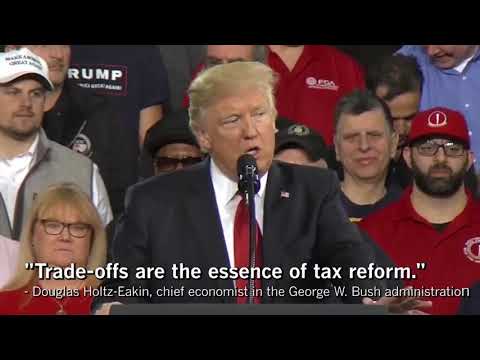

“Trade-offs are the essence of tax reform,” said Douglas Holtz-Eakin, repeating an axiom of the trade. Holtz-Eakin served as chief economist in the George W. Bush administration, led the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office and advised John McCain’s presidential campaign on domestic and economic policy.

Changing almost any element of the tax code requires some to pay more and others to pay less or else it requires passing the pain to future generations in the form of deficits. The inevitability of trade-offs is one of the main reasons the issue bedevils lawmakers from both parties and why the code has not been rewritten for more than three decades.

“The winners are always skeptical that they actually won, so they’re sort of modestly supportive. The losers are sure they’ve lost, so they’re very loud,” said Steve Rosenthal, a senior fellow at the Tax Policy Center, a Washington-based think tank.

Trump’s campaign rhetoric almost exclusively stressed lowering rates, offering little to no detail on how to pay for those cuts or streamline the Talmudic-like set of regulations that govern what Americans must turn over to the IRS. As president, he has yet to outline his goals much beyond saying at a recent rally, “I want to cut the hell out of taxes.”

Trump has left almost everything else up in the air. He even has waffled on when he will tackle the issue, saying right after the failure of his healthcare bill last month that he would proceed to taxes immediately, then suggesting in an interview last week with Fox Business that he would prefer to give healthcare another try first.

Congressional Republicans have floated a number of ideas that would lower tax rates for corporations and individuals, eliminate most deductions and require companies to pay taxes on imports. Analysts have cautioned that many of the plans would worsen the budget deficit and that they all would favor higher earners, which could fracture Trump’s political coalition.

Holtz-Eakin knows the political consequences of tough choices. He said he still suffers post-traumatic stress from the 2008 campaign in which McCain proposed eliminating the deduction on employer-sponsored health insurance, one of the most popular pieces of the tax code. Barack Obama ran a relentless and effective advertisement showing an unraveling ball of yarn with the warning that McCain’s plan could “leave you hanging by a thread” with higher taxes and no health insurance.

Yet Obama’s electoral victory did not translate into success at rewriting tax rules, even as he agreed with Republicans that corporate rates were too high.

Ronald Reagan, the last president to overhaul the tax system, had nearly everything going for him politically when he tackled the task in the mid-1980s. He won 49 of 50 states in his reelection, which prominently featured tax reform. Although Democrats controlled the House of Representatives, the powerful leader of the tax-writing committee, Dan Rostenkowski of Illinois, wanted to cut a deal and became one of its chief salesmen.

The economy was growing strongly as it recovered from the recession of the early 1980s, and Reagan’s approval ratings were headed toward their peak of 60%.

“There was a certain amount of trust people had for him. … You kind of gave him the benefit of the doubt,” said James C. Miller III, who served as Reagan’s budget director.

“There were a lot of trade-offs in that bill,” he noted. Although Reagan presented himself as the avatar of smaller government, “the bill actually made the number of pages in the federal register larger, not smaller.”

Yet passing the 1986 tax reform law still took more than two years, and it required Reagan to sell the public on his notion of fairness, which included lowering the top rates, raising the bottom rates and eliminating many tax shelters.

“What’s missing when compared to the experience of 30 years ago is a presidential or a White House or a Treasury Department proposal,” said Jeffrey H. Birnbaum, who co-wrote a book on that tax overhaul called “Showdown at Gucci Gulch.” He is now a public relations consultant whose clients include a group seeking lower rates.

“We don’t know what the president favors or doesn’t,” Birnbaum added. “His support for a specific set of principles is essential, in my view, to powering the effort.”

Absent Trump’s leadership, congressional Republicans are divided over basic issues such as whether to create new taxes on consumption or emphasize simplicity and the ability to file on a postcard.

Many tax analysts and advocates say cuts alone — without changes to pay for them — do not amount to true tax reform, though they ultimately may be marketed that way. Even Rep. Mark Meadows, a North Carolina Republican who leads a group in Congress that says it cares deeply about deficits, has said he may support a plan that does not pay for itself.

“We’re not there yet,” White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer said recently, when asked whether Trump would insist that his tax plan pay for itself. “As the plan develops and there’s a cost put on it, that’s going to be a decision that gets looked at, as well as what are the economic-growth and job-creation aspects to it,” Spicer said.

Spicer outlined three broad goals: tax simplification, lower rates and job growth.

Veterans of the process say Trump does not need to emphasize the detailed trade-offs to prevail. He does need to make the case that the overall benefits will outweigh the pain, and that Americans will benefit broadly from whichever approach he chooses.

But the changes favored by Republicans could be a complicated sell, given Trump’s unusual coalition, which couples working-class Americans who have voted with Democrats in the past with more traditional business-friendly GOP voters.

A survey released Friday by the nonpartisan Pew Research Center revealed that a large majority — 62% of Americans — say they are bothered a lot that corporations do not pay their fair share of taxes, and 60% are bothered a lot that wealthy people do not pay a fair share. Fewer people — 27% — are bothered a lot by the amount they themselves pay in taxes. Only 20% were bothered a lot by the idea that poor people do not pay enough.

Republicans in the survey were far more sympathetic than the rest of the public to the tax burdens of corporations and the wealthy and also are more likely to be concerned with the system’s complexity, an issue that many Republican elected officials have highlighted.

Rep. Richard E. Neal of Massachusetts, the lead Democrat on the tax-writing committee, who favors lowering corporate tax rates from their current 35%, said it would be impossible to push them down to 25%, as many Republicans advocate, without eliminating popular deductions such as the home mortgage break.

But Neal said he does not yet understand whose influence is holding sway with Trump.

The president’s top economic advisor, Gary Cohn, recently paid a visit to his office, Neal said. They had a cordial conversation. But Neal offered a dose of bipartisan realism.

“I said to Cohn, ‘I’ve had at least five secretaries of the Treasury sit on the same couch you’re sitting on during the last 25 years to tell me they were going big on tax reform,’” Neal said.

Once the details emerge, the critics follow.

“There’s a constituency for just about every item in the code.”

Twitter: @noahbierman

ALSO

Georgia voters in this reliably Republican district may be preparing to ‘stick it’ to Trump

As Trump and Texas crack down on illegal immigration, Austin rebels

Former Defense Secretary William Perry on why we didn’t go to war with North Korea

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.