Trump falsely says Puerto Rico’s official hurricane death tally is inflated by Democrats

San Juan Mayor Carmen Yulín Cruz reacts to President Trump’s questioning a report putting the death toll from last year’s catastrophic hurricane in Puerto Rico at nearly 3,000. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

Reporting from Washington — President Trump on Thursday falsely accused Democrats of inflating Puerto Rico’s death toll from hurricanes Maria and Irma, insisting the total is much smaller than various studies have found — a contention that provoked widespread outrage even as the East Coast braced for a massive new storm.

The president’s rejection of the U.S. island’s official tally that nearly 3,000 people died after last year’s devastating hurricanes, and his suggestion that the toll wasn’t much greater than 18 deaths, was one of the most prominent examples to date of Trump’s instincts to deny accepted reality when he perceives it as criticism and to counter with conspiracy theories.

His statements in back-to-back morning Twitter posts came while millions of Americans were anxiously watching the path of Hurricane Florence as it headed toward the Carolinas. Trump for days has been focusing on federal preparations for that storm, recognizing that his administration’s response will be a key test of competency just weeks before the November election.

The president already had come under bipartisan fire this week after he called the federal government’s response last year in Puerto Rico an “incredible unsung success.”

His rhetoric has not only angered politicians in both parties, but it also stole attention from positive economic news and created another stumbling block for Trump’s Republican allies who face tight races, forcing them to respond to questions about the president’s statements. That danger was especially pronounced in Florida, where a large Puerto Rican population has grown significantly as people have fled the ravaged island.

In Puerto Rico, many residents went without power for nearly a year after Maria, the second and most destructive of two major storms, made landfall last Sept. 20. Reconstruction has lagged, leaving thousands of people living under tarps.

The government’s official death toll rose from about 17 when Trump visited in October to 64 and recently, after extensive research and public outcry, to 2,975 — the tally fixed by researchers commissioned by the island’s government.

Yet Trump tweeted, “3000 people did not die in the two hurricanes that hit Puerto Rico. When I left the Island, AFTER the storm had hit, they had anywhere from 6 to 18 deaths. As time went by it did not go up by much.”

Trump accused Democrats of reporting larger numbers “in order to make me look as bad as possible when I was successfully raising Billions of Dollars to help rebuild Puerto Rico.”

“If a person died for any reason, like old age, just add them onto the list,” he added. “Bad politics. I love Puerto Rico!”

The White House did not respond to a request to provide evidence of misreported deaths or other facts that would support Trump’s tweets.

In fact, several studies have attributed as many as thousands of deaths in Puerto Rico to the storms.

The Puerto Rican government’s tally of 2,975 is based on a months-long study by the George Washington University Milken Institute School of Public Health, which compared death rates in prior years with those in the six months after the storm hit.

Earlier this year, researchers led by Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health published a study in the New England Journal of Medicine putting the toll at between 800 and 8,000, and settling on 4,600 as a conservative estimate of deaths through the end of 2017. The New York Times, assessing Puerto Rico’s vital statistics in the 42 days after the storm, estimated 1,052 people had died as direct or indirect consequences of the hurricanes.

Other media organizations came to similar conclusions. By comparison, Hurricane Katrina in 2005 caused an estimated 1,000 to 1,800 deaths.

It’s common for death rates to climb even months after a natural disaster, given both the lingering damage and the fact that initial assessments are compiled in chaotic conditions. In Puerto Rico, many sick and injured residents went without adequate care and without power, food, medicines and clean water.

Even before Trump’s latest comments, feelings were raw in Puerto Rico, where many residents feel he epitomizes a view among some on the mainland U.S. that the island’s largely Latino population is somehow less than American.

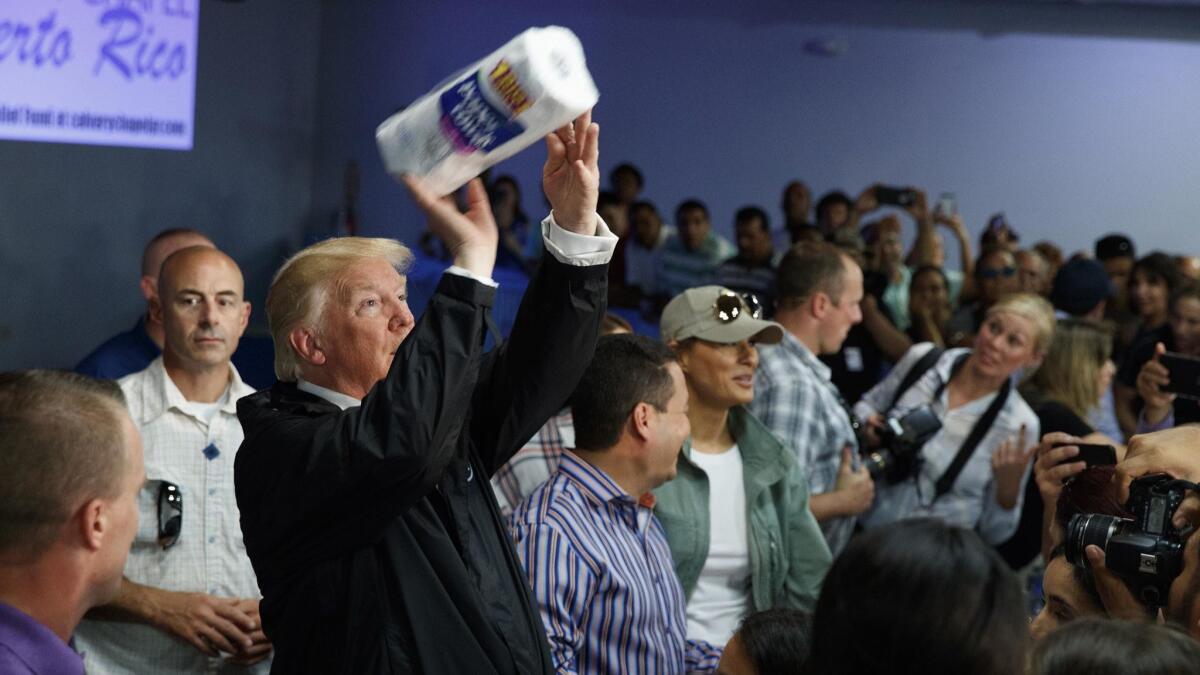

San Juan Mayor Carmen Yulin Cruz, a Democrat and a sharp critic of the federal government’s response, who has been one of the president’s frequent targets, recalled Trump’s October 2017 visit to the island, when he playfully tossed paper towels into a crowd, a gesture that struck many as insensitive.

“From the start, he looked at it as a way to position himself on the political spectrum,” Cruz said in an interview. “But what the world saw was a paper-towel-throwing bully who had no connection with reality and whose neglect allowed his government to turn their backs on the Puerto Rican people. And people died. And he still does not get it.”

Maytee Sanz, 42, who lives in Charlotte, N.C., was preparing for Florence on Thursday when relatives from Puerto Rico texted to ask whether she had seen the president’s tweet.

“This is like rubbing salt in the wound,” she said. “How can you disrespect the dead? It’s beyond my comprehension.”

Her grandfather, Raul Antonio Morales Moreira, died in a nursing home in the Puerto Rican town of Trujillo Alto in October. The 96-year-old diabetic lacked access to refrigeration for his insulin, she said.

Luz Rivera Perez, 63, whose San Juan home, with its leaking roof and water-damaged floors, is still in need of repair one year after Maria, said Trump has no idea what he is talking about when he calls the response a success. “He should go to the countryside to see all of the destroyed homes, where people haven’t been able to rebuild because they don’t have money,” she said. “Donald Trump lies.”

The island’s governor, Ricardo Rossello, has been mostly supportive of the president, but he also denounced Trump’s comments in a statement, saying that “the victims and the people of Puerto Rico do not deserve to have their pain questioned.”

“This is not the time to deny what happened,” he added. “It is the time to assure it never happens again.”

Trump’s advisors and allies have long struggled to adapt to his more incendiary tweets — choosing to ignore or reinterpret them when possible, and only respond when absolutely necessary. One White House official reached Thursday morning claimed not to have seen the latest tweets.

“There’s a degree of fatalism about it at this point,” said Michael Steel, a former spokesman for GOP congressional leaders, who is in frequent contact with White House advisors. “He’s going to do what he’s going to do.”

House Speaker Paul D. Ryan (R-Wis.), who often shows exasperation when reporters ask him about Trump’s comments, sounded Thursday as if he were trying to coax the president to accept reality by assuring him he would not take blame.

“Casualties don’t make a person look bad ... so I have no reason to dispute the numbers,” Ryan told reporters at the Capitol. “I was in Puerto Rico after the hurricane. It was devastated. This was a horrible storm.”

Other Republicans made similar statements. But the issue was especially complicated in Florida, with its increased population of Puerto Ricans. Gov. Rick Scott, a Republican Trump ally in a tight race for a U.S. Senate seat, has tried especially hard to make inroads with the Puerto Rican community, which traditionally leans Democratic. He disavowed Trump’s tweet, as did other Republicans in the state, including Rep. Ron DeSantis, who is running to succeed Scott as governor, and Sen. Marco Rubio.

“I disagree with@POTUS — an independent study said thousands were lost and Gov. Rossello agreed,” Scott tweeted. “I’ve been to Puerto Rico 7 times & saw devastation firsthand. The loss of any life is tragic; the extent of lives lost as a result of Maria is heart wrenching. I’ll continue to help PR.”

Mac Stipanovich, a veteran Republican strategist in the state and a Trump critic, said the political fallout there would vary, depending on how closely a candidate is tied to the president. He predicted lawmakers like Rep. Carlos Curbelo, a South Florida Republican who has distanced himself from Trump, would not be affected, whereas DeSantis, who has based his run for governor on his close ties to the president, could face more difficulties.

“If it’s four voters or 4,000, I have no idea, but why throw away the four votes?” Stipanovich said. “The answer is because Trump wanted to vindicate himself against allegations that his administration had performed poorly.”

Follow the latest news of the Trump administration on Essential Washington »

[email protected] | Twitter: @noahbierman

Bierman reported from Washington, Esquivel from San Juan. Times staff writer Sarah D. Wire in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.